A People's Tragedy (80 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

It was Martov who came up with the idea of exchanging the Russian Marxist exiles in Switzerland for the German citizens interned in Russia. With the help of their Swiss comrades, the Russian exiles made contact with the German authorities, who quickly saw the advantage of letting the Bolsheviks, and other socialist groups opposed to the war, go back to Russia to stir up discord there. They even helped to finance their activities, although this should not necessarily be taken to mean, as many people were later to argue, that the Bolsheviks were German agents.49 The Provisional Government was not keen on the idea of an exchange — Miliukov was determined to oppose it in view of Lenin's well-known defeatist views — and dragged its heels over the negotiations. Martov and most of the Menshevik exiles were prepared to wait. But Lenin and thirty-one of his comrades were impatient enough to go ahead with the German plan without the sanction of the Russian government. On 27 March they left

* Valentinov, who knew Lenin well in Switzerland, wrote: 'He would never have gone on to the streets to fight on the barricades, or stand in the line of fire. Not he, but other, humbler people were to do that . . . Lenin ran headlong even from emigre meetings which seemed likely to end in a scuffle. His rule was to "get away while the going was good" — to use his own words — meaning from any threat of danger. During his stay in Petersburg in 1905—6 he so exaggerated the danger to himself and went to such extremes in his anxiety for self-preservation that one was bound to ask whether he was not simply a man without personal courage.'

on a German train from Gottmadingen on the Swiss border and travelled via Frankfurt, Berlin and Stockholm to Petrograd. The train, which had only one carriage, was 'sealed'

in the sense that no inspections of passports or luggage were carried out by the Germans on the way. Lenin worked alone in his own compartment, while his fellow travellers, much to his annoyance, drank and sang in the corridor and the other compartments.

Smoking was confined to the lavatory and Lenin ordered that all non-smokers should be issued with a 'first class' pass that gave them priority to use the lavatory over the smokers with their 'second class' passes. As Radek quipped, it seemed from this piece of minor social planning that Lenin was already preparing himself to 'assume the leadership of the revolutionary government'.50 The 'sealed train' was an early model of Lenin's state dictatorship.

Lenin arrived a stranger to Russia. Apart from a six-month stay in 1905—6, he had spent the previous seventeen years in exile abroad. Most of the workers who turned out to meet him at the Finland Station could never have seen him before.* 'I know very little of Russia,' Lenin once told Gorky. 'Simbirsk, Kazan, Petersburg, exile — that is all I know.' During 1917 he would often claim that the mass of the ordinary people were even further to the Left than the Bolsheviks. Yet he had no experience of them, and knew only what his party agents told him (which was often what he wanted to hear).

Between 5 July and the October seizure of power Lenin did not make a single public appearance. He barely set foot in the provinces. The man who was set to become the dictator of Russia had almost no direct knowledge of the way its people lived. Apart from two years as a lawyer, he had never even had a job. He was a 'professional revolutionary', living apart from society and supporting himself from the party's funds and from the income of his mother's estate (which he continued to draw until her death in 1916). According to Gorky, it was this ignorance of everyday work, and the human suffering which it entailed, which had bred in Lenin a 'pitiless contempt, worthy of a nobleman, for the lives of the ordinary people .. . Life in all its complexity is unknown to Lenin. He does not know the ordinary people. He has never lived among them.'51

'Well there it is,' Lenin wrote to Kollontai on 2 March. 'This first stage of the revolution (born of the war) will be neither the last, nor confined to Russia.' Lenin was already thinking of a second revolution — a revolution of his own. In his five 'Letters from Afar', written between 7 and 26 March, he mapped out his party's programme for the transition from 'the first to the

* Many of the workers who came to greet Lenin may have turned up on the expectation of free beer. Welcoming receptions for returning party leaders had become a regular feature of life in the capital since the revolution, and for many of the workers they had become a pretext for a street party. This was particularly relevant in the case of Lenin's return from exile, since it coincided with the Easter holiday.

BETWEEN REVOLUTIONS

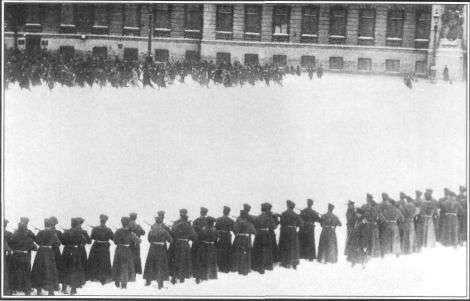

38 The Tsar's soldiers fire on the demonstrating workers in front of the Winter Palace, 9

January ('Bloody Sunday') 1905.

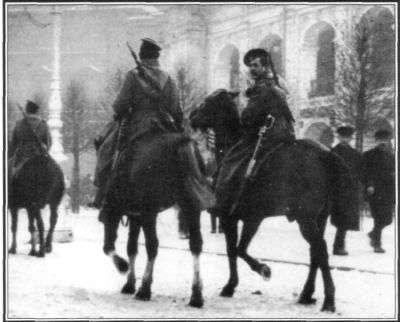

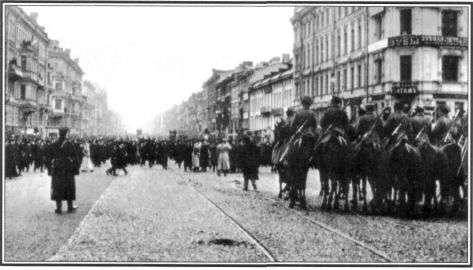

39 Demonstrators confront a group of mounted cossacks on the Nevsky Prospekt in 1905.

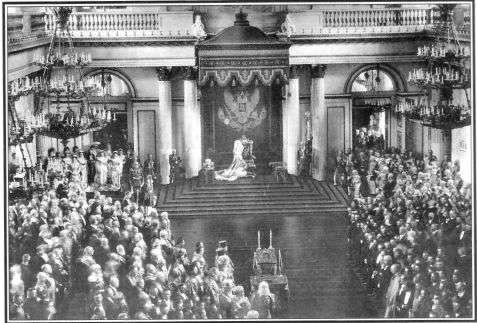

40 The opening of the State Duma in the Coronation Hall of the Winter Palace, 27 April 1906. The two Russias - autocratic and democratic - confronted each other on either side of the throne. On the left, the appointees of the crown; on the right, the Duma delegates.

41 The Tauride Palace, the citadel of Russia's fragile democracy between 1906 and 1918.

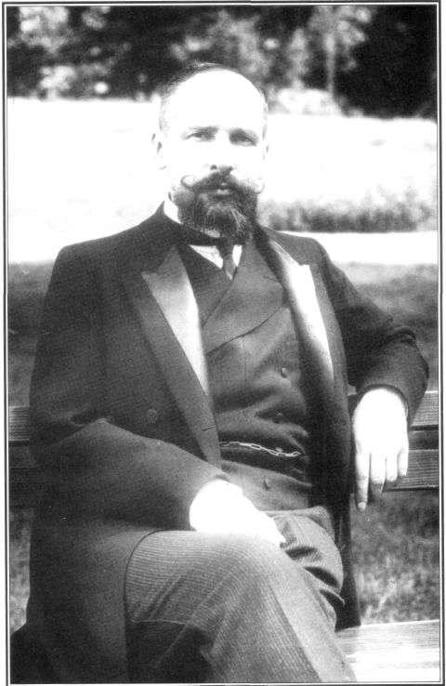

42 Petr Stolypin in 1909. Many things about the Prime Minister - his provincial background and his brilliant intellect - made him an outsider to his own bureaucracy.

43 Patriotic volunteers pack parcels for the Front, Petrograd, 1915. The war campaign activated and politicized the public.

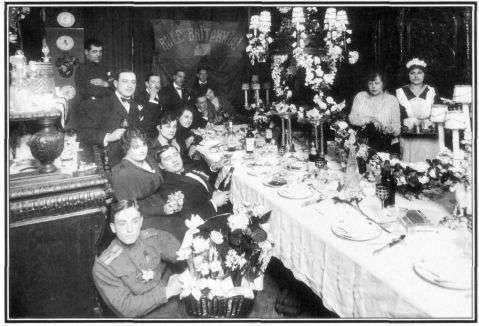

44 The smart set of Petrograd see in the New Year of 1917. Note the anglophilia, the whisky and champagne. This sort of ostentatious hedonism had become quite common among the upper classes; and at a time of enormous wartime hardships it was deeply resented by the workers.

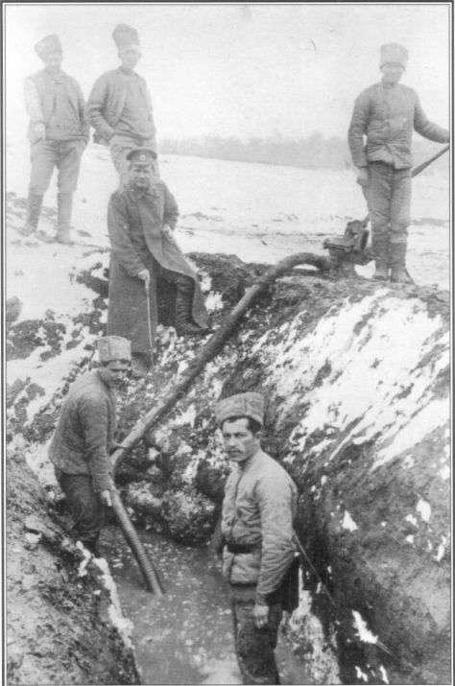

45 Troops pump out a trench on the Northern Front. The poor construction of the trenches, a science which the tsarist Staff had never thought worth learning, was a major cause of the huge Russian losses in the First World War.