Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (10 page)

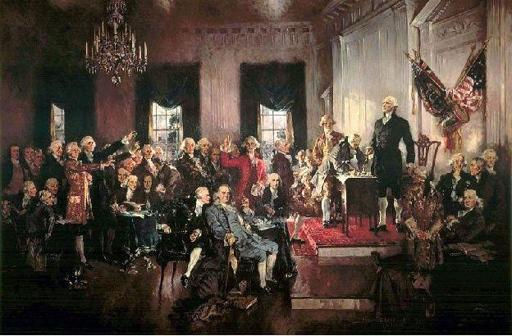

Independence Hall

On May 14, 1787, the Constitutional Convention began in Philadelphia, and Madison was not only one of the first to arrive, but he had also brought with him a plan for a new national government. This plan became known as the Virginia Plan because it had the support of Virginia's delegation, of which James Madison was a member. Madison had researched ancient and contemporary constitutions for over a month to help him devise his Virginia Plan, while most of the other delegates arrived empty handed and hadn’t even cracked open a single book on the subject. That was due to the fact that for most delegates, the original intention of the Philadelphia Convention was not to create an entirely new government but to simply reform the old one. When Madison arrived in Philadelphia with a plan in hand, the Virginia Plan, he quickly circulated it among the delegates before proceedings even began.

Madison did not formally introduce the Virginia Plan himself. Instead, Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph formally presented it to the Convention. When voting whether to consider it or not, the delegates were implicitly voting for a complete overhaul of the Articles of Confederation. Secause the Virginia plan was so different from the Articles, voting to consider it effectively meant the Convention was voting for a whole new Constitution. Almost unanimously, the Convention agreed to draft a new Constitution, and the debate began in earnest.

Although the U.S. Constitution took some obvious departures from Madison's Virginia Plan, Madison’s work was the blueprint for the Constitution. Madison’s Plan called for a bicameral legislature, with both chambers made up of delegates from the 13 states, proportional to each state's population. This thus favored large states like Virginia, which was the largest at the time, and the Virginia Plan became known as the Big State Plan. Madison's Plan, however, also made more lasting contributions by laying out the terms of the separation of powers, and a three-branch government of legislative, judicial and executive branches. Each branch was to be separate from the other two, and each branch would be given different powers and functions that ensured they could “check” the power of the other two branches. This was a stark departure from other forms of government, such as the English Parliamentarian system, where the Prime Minister was both a member of the executive and legislative branches of government.

Surprisingly, most all delegates agreed on most of Madison's basic outline. While the national legislature under the Articles of Confederation only had one house, it was bicameral legislatures that were more common among state governments, and the British Parliament was also a bicameral model. Madison saw the unicameral legislature as prone to extremism, because there was no upper house which could prevent public sentiment from provoking unwise legislation. In other words, Madison felt the unicameral legislature was too democratic, a sentiment shared by a majority of the delegates, who supported the separation of powers and a bicameral legislature. The idea of having a directly elected House and an indirectly elected Senate were uncontroversial. On the other hand, Hamilton’s idea of an elected executive serve for life was roundly rejected by most delegates, who considered that tantamount to a monarchy.

While the structure of the three branches of governments was widely agreed upon, the way the two houses of the national legislature were apportioned was a point of major dispute. Smaller states quickly rallied in opposition to Madison's Big State Plan. They came to favor, with some amendments, the New Jersey Plan, which provided for a unicameral legislature of equal representation for all states. Most of the New Jersey Plan was not seriously considered, but the notion that all states should have equal representation obviously made its way to the Constitution’s formula for the U.S. Senate. Madison opposed the plan, arguing that the small states need not worry about being domineered by the larger ones. Madison and Hamilton together argued that the large states, like New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Virginia, were all so different from each other that they would never form an alliance that dominated the national government at the expense of the small states. They also thought other states with similar economic and social conditions could ally with a large one, making the point of large state dominance a moot one. The New England states would rally around Massachusetts while the Southern states would look to Virginia as a leader, and the mid-Atlantic would split between Pennsylvania and New York.

Representatives from small states remained unconvinced, however. As a compromise, Roger Sherman of Connecticut proposed a plan that combined the favorable elements of Madison's Plan with those from New Jersey's. The resulting Connecticut Plan called for one legislative body with proportional representation and another with equal representation.

Other thorny issues were also sorted out during the summer, most notoriously the question of how to count slaves as part of a state’s population. But by the end of the summer of 1787, the ideas were sorted out and the Constitution of the United States, which remains the longest continually operating constitution, had been born. James Madison was hailed as the Father of the Constitution because his broad outline, with only some modification, ultimately formed the final governing document.

Madison obviously did not get everything he wanted out of the Constitution that was eventually drafted, but nobody else did either. On the last day of the Convention, September 17, 1787, the date the Constitution was signed, Benjamin Franklin gave a speech that poignantly summed up many of the delegates’ thoughts when explaining why he was going to vote in favor of the Constitution:

“I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them: For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others… In these sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults, if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us, and there is no form of Government but what may be a blessing to the people if well administered, and believe farther that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in Despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic Government, being incapable of any other. I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution. For when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men, all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected? It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies, who are waiting with confidence to hear that our councils are confounded like those of the Builders of Babel; and that our States are on the point of separation, only to meet hereafter for the purpose of cutting one another's throats. Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best. The opinions I have had of its errors, I sacrifice to the public good. I have never whispered a syllable of them abroad. Within these walls they were born, and here they shall die.”

The famous painting “

Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States”.

Madison is front and center, seated to Ben Franklin’s left. Hamilton is on Franklin’s right.

Working to Ratify the Constitution in Virginia

The Convention was over, but that didn’t mean the Constitution immediately took effect. After the final document was agreed to in Philadelphia, it still had to be ratified by the colonies, which required the delegates to attempt to argue for or against it. Between October 1787 and August 1788, very public debates took place between supporters of the new constitution and opponents. At stake was whether the United States would remain governed by the Articles of Confederation or would adopt the new Constitution. Today the Articles of Confederation are looked at as an archaic failure, but it’s important to remember that ratifying the Constitution basically required the 13 individual states to give up significant amounts of their own sovereignty.

Madison had no qualms about ratifying the Constitution, but his state was far less eager to cede power to a federal government. As one of the biggest and most influential states, many in Virginia were wary about the state losing its weight in a national government that equally proportioned representation from all states in one house of Congress. Virginia was especially critical to the ratification of the Constitution, because many other states were unwilling to ratify the Constitution without Virginia's support, believing the nation would fail without Virginia.

Madison was a delegate to the Virginia ratification convention, where some of his former colleagues now became formidable opponents. The most prominent among these were Patrick Henry and George Mason, who both thought the large central government would trample on states' rights. Madison, however, eventually rose to the occasion and persuaded Henry, Mason and other prominent Virginians to support the Constitution. He did so by offering concessions, some explicit and others implicit. Among these were his promise to support a later Bill of Rights and his suggestion that a Virginian would likely dominate the Presidency, which proved correct from 1789-1825, with the exception of John Adams’s one term.

The Federalist Papers

Having secured Virginia, Madison, together with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, worked to sell the new Constitution to the American people. Hamilton and Jay, both from New York, were also from a large state that was hesitant to ratify the Constitution. Together the three anonymously authored a series of letters and articles promoting the merits of the Constitution. These writings collectively became known as the

Federalist Papers

, which still remain among the most famous and influential political writings in the nation’s history.

Although the premise of the Federalist Papers was originally Hamilton’s idea, it was Madison who made the finest contributions. Among Madison's notable submissions were his arguments about federalism's compatibility with a pluralist society in Federalist #10 and Federalist #51. Here, Madison opposed factionalism but argued that federalism provided the best chance for cohesion in a society as politically, religiously and culturally diverse as the United States. In Federalist #39, he argued that the Constitution's federal/state dichotomy was best for the United States, and he further explained the system of checks and balances in Federalist #48. Together, these four articles in the

Federalist Papers

continue to be the most widely-read, and they continue to outshine Jay’s and Hamilton’s contributions.