Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (42 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Of course, so many things are

not the same “ting”

in life. Let us generalize the conflation.

This lesson “not the same thing” is quite general. When you have optionality, or some antifragility, and can identify betting opportunities with big upside and small downside, what you do is only remotely connected to what Aristotle thinks you do.

There is

something

(here, perception, ideas, theories) and a

function of something

(here, a price or reality, or something real). The conflation problem is to mistake one for the other, forgetting that there is a “function” and that such function has different properties.

Now, the more asymmetries there are between the

something

and the

function of something,

then the more difference there is between the two. They may end up having nothing to do with each other.

This seems trivial, but there are big-time implications. As usual science—not “social” science, but smart science—gets it. Someone who escaped the conflation problem is Jim Simons, the great mathematician who made a fortune building a huge machine to transact across markets. It replicates the buying and selling methods of these sub–blue collar people and has more statistical significance than anyone on planet Earth. He claims to never hire economists and finance people, just physicists and mathematicians, those involved in pattern recognition accessing the internal logic of things, without theorizing. Nor does he ever listen to economists or read their reports.

The great economist Ariel Rubinstein gets the green lumber fallacy—it requires a great deal of intellect and honesty to see things that way. Rubinstein is one of the leaders in the field of game theory, which consists in thought experiments; he is also the greatest expert in cafés for thinking and writing across the planet. Rubinstein refuses to claim that his knowledge of theoretical matters can be translated—by him—into anything directly practical. To him, economics is like a fable—a fable writer is there to stimulate ideas, indirectly inspire practice perhaps, but certainly not to direct or determine practice. Theory should stay independent

from practice and vice versa—and we should not extract academic economists from their campuses and put them in positions of decision making. Economics is not a science and should not be there to advise policy.

In his intellectual memoirs, Rubinstein recounts how he tried to get a Levantine vendor in the souk to apply ideas from game theory to his bargaining in place of ancestral mechanisms. The suggested method failed to produce a price acceptable to both parties. Then the fellow told him: “For generations, we have bargained in our way and you come and try to change it?” Rubinstein concluded: “I parted from him shamefaced.” All we need is another two people like Rubinstein in that profession and things will be better on planet Earth.

Sometimes, even when an economic theory makes sense, its application cannot be imposed from a model, in a top-down manner, so one needs the organic self-driven trial and error to get us to it. For instance, the concept of specialization that has obsessed economists since Ricardo (and before) blows up countries when imposed by policy makers, as it makes the economies error-prone; but it works well when reached progressively by evolutionary means, with the right buffers and layers of redundancies. Another case where economists may inspire us but should never tell us what to do—more on that in the discussion of Ricardian comparative advantage and model fragility in the Appendix.

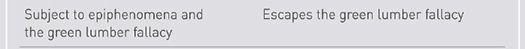

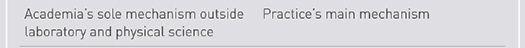

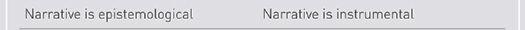

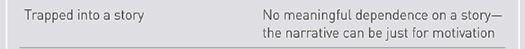

The difference between a narrative and practice—the important things that cannot be easily narrated—lies mainly in optionality, the missed optionality of things. The “right thing” here is typically an antifragile payoff. And my argument is that you don’t go to school to learn optionality, but the reverse: to become blind to it.

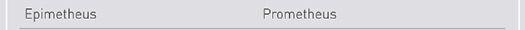

In Greek legend, there were two Titan brothers, Prometheus and Epimetheus. Prometheus means “fore-thinker” while Epimetheus means “after-thinker,” equivalent to someone who falls for the retrospective distortion of fitting theories to past events in an ex post narrative manner. Prometheus gave us fire and represents the progress of civilization, while Epimetheus represents backward thinking, staleness, and lack of intelligence. It was Epimetheus who accepted Pandora’s gift, the large jar, with irreversible consequences.

Optionality is Promethean, narratives are Epimethean—one has reversible and benign mistakes, the other symbolizes the gravity and irreversibility of the consequences of opening Pandora’s box.

You make forays into the future by opportunism and optionality. So far in

Book IV

we have seen the power of optionality as an alternative way of doing things, opportunistically, with some large edge coming from asymmetry with large benefits and benign harm. It is a way—the only way—to domesticate uncertainty, to work rationally without understanding the future, while reliance on narratives is the exact opposite: one is domesticated by uncertainty, and ironically set back. You cannot look at the future by naive projection of the past.

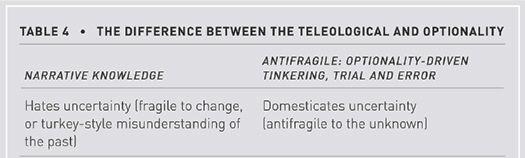

This brings us to the difference between doing and thinking. The point is hard to understand from the vantage point of intellectuals. As Yogi Berra said, “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice; in practice there is.” So far we have seen arguments that intellect is associated with fragility and instills methods that conflict with tinkering. So far we saw the option as the expression of antifragility. We separated knowledge into two categories, the formal and the Fat Tonyish, heavily grounded in the antifragility of trial and error and risk taking with less downside, barbell-style—a de-intellectualized form of risk taking (or, rather, intellectual in its own way). In an opaque world, that is the only way to go.

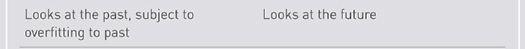

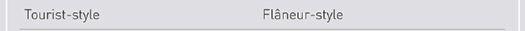

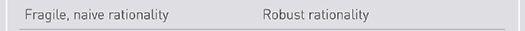

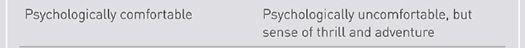

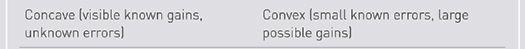

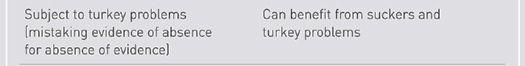

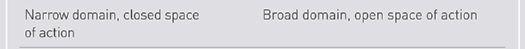

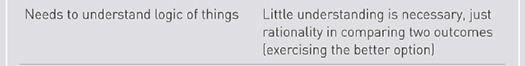

Table 4

summarizes the different aspects of the opposition between narrating and tinkering, the subject of the next three chapters.