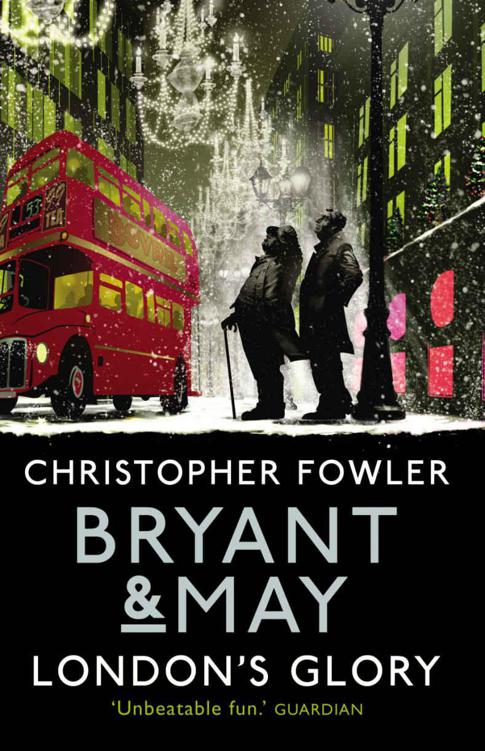

Bryant & May - London's Glory: (Short Stories) (Bryant & May Collection)

Read Bryant & May - London's Glory: (Short Stories) (Bryant & May Collection) Online

Authors: Christopher Fowler

‘Do you remember that corpse we found in the snow with nobody else’s footprints around it?’ asked Arthur Bryant. ‘And the department store Santa Claus whose gift caused a death? I thought I’d write up some of our more curious cases.’

‘All right,’ said John May, ‘but don’t make them sound like a bunch of ridiculous old paperback mysteries this time . . .’

Bryant did, of course, and here they are: eleven missing cases from the files of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit, with dark crimes, strange suspects and some added surprises. From the sinister circus ringmaster to the femme fatale who coolly announces she’s about to kill a man, from the foggy fifties to the swinging sixties and the present day, and including a story narrated by Janice Longbright, the unit’s long-suffering detective sergeant, these are tales of the PCU doing what it does best – solving the city’s most peculiar crimes.

Whether you’re a Bryant and May aficionado or a newcomer to their singular world, you’ll find a confounding story to suit your tastes in this collection from ‘the crime fiction series quite unlike anything else being produced in the UK’.

CONTENTS

Introduction: Still Getting Away with Murder

Illustration of the Peculiar Crimes Unit

Bryant & May:

Dramatis Personae

Bryant & May and the Secret Santa

Bryant & May and the Nameless Woman

Bryant & May and the Seven Points

Bryant & May and the Blind Spot

Bryant & May and the Bells of Westminster

Bonus Story: Bryant & May’s Mystery Tour

Bryant & May: The Cases So Far

Arthur Bryant’s Secret Library

For Clare, with love and pride

STILL GETTING AWAY WITH MURDER

Why have crime novels stuck around for so long? In theory they should have died out decades ago. After all, there’s nothing remotely realistic about them. In real life the murder rate is falling and there are very few clever killers, so why do we want to believe in fictional crime tales?

Let me try to answer this with an illustration of the problem.

Some years ago, I found myself locked inside a Soho taxi late at night while my driver was viciously attacked by a pair of City bankers. The driver had shouted at the men, who were drunk and had hammered on the bonnet of his cab, and the drunks had dragged him through the window of his vehicle and beaten him senseless. I agreed to act as the driver’s witness, but outside the courtroom the police persuaded the plaintiff to drop his case in exchange for enough cash to repair his vehicle and compensate for his injuries. The officers said court proceedings would only cause everyone more hurt and trouble. It was a reasonable solution, if an unexciting one. The police shifted a case off their books and the victim seemed happy, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that he had lost out.

In Britain, we have ‘equality of arms’, which allows the same resources to be made available to both defence and prosecution, and broadly speaking this idea of balance filters down through the system. There’s a reason why the Old Bailey’s statue of Justice holds scales. It means we don’t get such outrageous courtroom dramas as O. J. Simpson fiddling with a glove, but the end result is often fairer.

If you’ve ever been the victim of a crime, you’ll know that it’s a very different experience from its fictional equivalent. Police stations are like hospitals: utilitarian, brightly lit, overflowing with paperwork, staffed by overworked people who barely notice you, and most of what goes on takes place behind the scenes. The rest is just waiting around and trying to reconcile your anger and frustration with the orderly procedures you have to face. If crime fiction accurately reflected this reality it would be dead, so we augment it.

Yet we writers are still keen to convince you that our latest murder mysteries are grittily realistic. They aren’t. They never were and never will be. How many killers are captured while they’re in the middle of their slaughter sprees? How many have ever planned a series of murders according to coded biblical signs? How many leave abstract clues for a single detective and get caught just as they’re about to strike again? Only some of the psychological-suspense writers are exempt from these lunacies.

Crime fiction is a construct, a device for torquing tension, withholding information and springing surprises. Yet every month dozens of crime novels appear that promise us new levels of realism, when they patently supply the reverse. We’ll happily believe that the murder rate in Morse’s Oxford equals that of Mexico City if the story is told with conviction, or that the villages of the

Midsomer Murders

are thatched-roof hellholes more like the Bronx in the 1970s.

The latest census data about Britain reveals that the country is changing fast, and economic mobility is a major catalyst. However, there is a part of England that forever has an alcoholic middle-aged copper with a beloved dead wife, investigating a murdered girl who turns out to be an Eastern European sex worker. This idea might have surprised us a couple of decades ago, but it’s still being sold to us with monotonous regularity. It’s not gritty, it’s a comforting cliché.

While judging the CWA Gold Dagger Award I had to read a great many books which were interchangeable. It was shocking to think that they made it through the process of agent, reader, editor, commissions panel and proofer without anyone pointing out that opening a novel with a detective being called to a patch of waste ground to look at a slaughtered girl was not original. Originality has a tendency to decrease one’s popularity.

Crime fiction accounts for more than a third of all fiction published in the UK, but there are relatively few contemporary London stories being told with audacity and flair. This is odd, because crime with an element of black comedy is something we do incredibly well, from films like

The Ladykillers

and

Kill List

to authors like Kyril Bonfiglioli, Joyce Porter and the wonderful, underrated Pamela Branch. Few crime writers stray from the narrow path set by publishers in the wake of Nordic Noir. Stieg Larsson’s books were proof that you could get away with anything if you said it with a straight face. They’re very enjoyable reads, but patently absurd. Shows like

The Killing

and

The Bridge

made for excellent television, but their success has only exacerbated the problem for authors. As Tony Hancock once said, ‘People respect you more when you don’t get laughs.’

We are told that readers want veracity, but readers will accept that a murderer is stalking London according to the rules of a Victorian tontine, even though they’ll ask why your detective doesn’t age in real time. I’ve coped with the fact that Bryant and May are ancient and getting older by providing a suitably outrageous explanation in one of the later books.

Britain’s Golden Age mysteries frequently featured surreal crimes investigated by wonderfully eccentric sleuths. From Gladys Mitchell and Margery Allingham in the thirties to Peter Van Greenaway and Peter Dickinson in the sixties, the form was treated as something joyous and playful.

The Notting Hill Mystery

, which many regard as the first detective novel, was republished by the British Library and consists of letters, reports, floor plans and notes. Dennis Wheatley created a similar set of whodunnit-dossiers containing photographs, bloodstained material, a burned match, a lock of hair and other pieces of evidence in little bags. Even though his mysteries weren’t very good they were at least great fun.

They have been followed by too many doorstops of unrelenting grimness. Meanwhile, a handful of characters have become TV brands: Poirot, Holmes, Morse, Marple. Every year delivers another crate of old wine in new bottles. Kim Newman, whose own excellent Holmes books have a wonderful Gothic quality, has pointed out that TV doesn’t need to purchase new ideas so long as it can get away with stealing old ones.

I would argue that what we once loved, and what we’re not getting very much of these days, is murder mysteries which are as enjoyable from one page to the next as they are puzzling in their denouements. The beauty of crime tales from writers like Charlotte Armstrong, Edmund Crispin and Robert Van Gulik is that they were first and foremost fine reads, sometimes to the point where the solution to the crime was almost incidental.

There’s a quote from Barnes Wallis, the inventor of the bouncing bomb that destroyed the Ruhr dams in the Second World War, who said, ‘There is nothing more satisfying than showing that something is impossible, then proving how it can be done.’ That was what interested me about mystery writing from an early age. Well, that and my mother saying, ‘If you write a book it will remain in the library long after you’re dead.’ If any of you have read my memoir

Paperboy

you’ll know it’s typical of her to say ‘after you’re dead’ to a nine-year-old.

I write a weekly column for the

Independent on Sunday

called ‘Invisible Ink’, about once massively popular authors who have now become a minority taste or who have disappeared altogether, and it’s surprising how many wrote over a hundred books before vanishing into collective forgetfulness. They fade from popularity because tastes change, or their readers change, or the authors themselves change.

While I was researching the now virtually unread but once incredibly popular crime writer Margery Allingham, I discovered that she regarded a crime novel as a box with four sides: ‘a killing, a mystery, an enquiry and a conclusion with an element of satisfaction in it’. Her plan – which I think is a good template for all popular novels – was to reduce books like stock, to boil them to a kind of thick broth of a language that tasted rich enough to satisfy and left you wanting to copy down the recipe. Allingham believed in the ‘plum pudding principle’: you provide your readers with a plum every few bites, to keep them interested in the whole pudding. Dickens famously did this, of course, and so in his own way does Mr Dan Brown. Allingham has an extraordinary richness to her writing – it’s allusive, witty, bravura stuff – but it’s a window to an English mindset that is now completely lost.

I fell for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle because he conveyed the creeping pallor of Victorian street life, the fume-filled taverns where a man might find himself propositioned by a burglarizing gargoyle, the Thames-side staircases where gimlet-eyed doxies awaited the easily duped. Even his cheerful scenes felt vaguely gruesome: shopkeepers would drape a Christmas goose around a character’s neck like a feather boa; and the welcoming yellow light of a first-floor window could somehow suggest that its tenant was lying dead on the floor. Fog muffled murderers’ footsteps and London sunlight was always watery. The Holmes adventures were virtually horror stories. Men went raving mad in locked rooms, or died of fright for no discernible reason. Women were simply unknowable.

And even when you found out how it was done or who did it, what kind of lunatic would choose to kill someone by sending a rare Indian snake down a bell-pull? Who in their right mind would come up with the idea of hiring a ginger-haired man to copy out books in order to provide cover for a robbery?

Graduating to the Agatha Christie books, the initial thrill of discovering such plot ingenuity also created a curious sense of dissatisfaction. How were you supposed to identify with any of the characters? On my street there weren’t any colonels, housemaids, vicars, flighty debutantes, dowager duchesses or cigar-chomping tycoons. Certainly, none of our neighbours had ever attended a country house party, let alone found a body in the library. Nobody owned a library, and country houses were places you were dragged around on Sunday afternoons. I never went shooting on the estate – although sometimes there

was

a shooting on an estate.