Bryant & May - London's Glory: (Short Stories) (Bryant & May Collection) (3 page)

Read Bryant & May - London's Glory: (Short Stories) (Bryant & May Collection) Online

Authors: Christopher Fowler

Londoners remember Soho’s Coach & Horses pub for its rude landlord Norman Balon, but few realize that it was the drinking hole of the Prince Edward Theatre’s scenery-shifters. One evening I overheard a huge tattooed shifter at the bar telling his mate, ‘I says to ’im, call yourself a bleeding Polonius? I could shit better speeches to Laertes than that.’

Well, write such dialogue down and you follow authors like Margery Allingham, Gerald Kersh, Alexander Baron and Joe Orton, who were clearly fascinated by London’s magpie language and behaviour.

In the process of finding subjects for investigation, I’ve covered the Blitz, theatres, underground rivers, pre-Raphaelite artists, tontines, highwaymen, new British artists, the cult of celebrity, London pubs and clubs, land ownership, immigration, churches, the tube system, the Knights Templar, King Mob, codebreaking and Guy Fawkes, and still feel as if I’m only scratching at the surface of London history.

All writers are influenced by the things they’ve experienced, read and watched, by people they’ve met or heard about. The resulting books should not, I feel, reveal the whole of that iceberg. There must always be something more for the reader to discover.

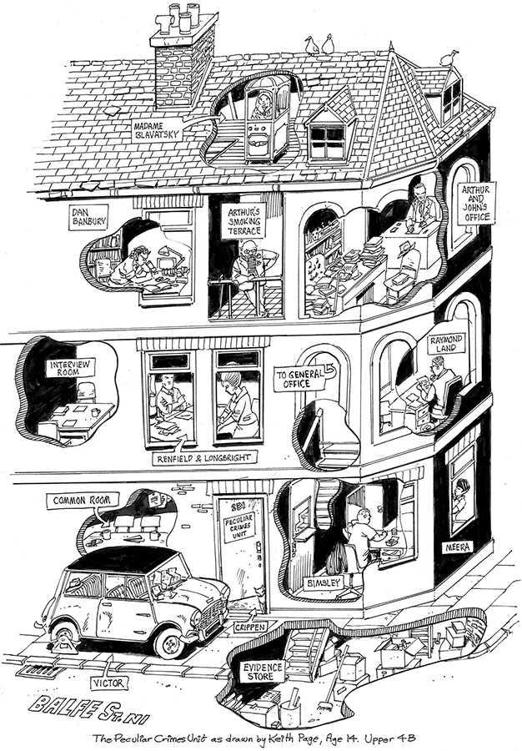

Which brings me to this volume. Short fiction is rather out of favour these days, but I couldn’t resist the opportunity of fleshing out some of the missing cases from the files of the Peculiar Crimes Unit. Think of this as a Christmas annual, a throwback to the days when such collections came with a few tricks and surprises. Ideally I would have included a selection of working models you could cut out. Maybe next time …

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

The Temporary Unit Chief dreams of escaping the PCU, but never manages to get away. An obsessive, meticulous member of the General and Administrative Division, he graduated in Criminal Biology, but often misses the point of his investigations. It’s said of him that ‘He could identify a tree from its bark samples without comprehending the layout of the forest.’ He can’t control his detectives. Or his wife.

Elderly, bald, always cold, scarf-wrapped, a wearer of shapeless brown cardigans and overlarge Harris tweed coats, Bryant is an enigma: well-read, rude, bad-tempered, conveniently deaf and a smoker of disgusting pipe tobacco (and cannabis for his arthritis, so he says). He’s a truly terrifying driver. He wears a hearing aid, has false teeth, uses a walking stick, and has to take a lot of pills. Once married (his wife fell from a bridge), he worked at various police stations and units around London, including Bow Street, Savile Row and North London Serious Crimes Division. He shares a flat with long-suffering Alma Sorrowbridge, his Antiguan landlady.

Born in Vauxhall, John is taller, fitter, more charming and personable than his partner. He’s technology-friendly, three years younger than Bryant, and drives a silver BMW. A sometimes melancholy craver of company, he leaves the TV on all the time when alone. He walks to Waterloo Bridge most nights with Bryant for ‘thinking time’. Vain and a bit of a ladies’ man, he lives in a modernist, barely decorated flat in Shad Thames. He’s divorced; his son and granddaughter now live in Canada.

Janice is a career copper; her mother Gladys worked for Bryant. She models herself on 1950s and 1960s film stars, and prides herself on looking glamorous. She’s smart but tough, and hates to show her true feelings. Dedicated to Arthur and John, she always puts work before her personal life. She lives a solitary existence in her flat in Highgate, and keeps a house brick in her handbag for dealing with unwanted attention.

The unit’s crime scene manager and IT expert is almost normal compared to his colleagues. He’s a sturdy, decent sort, married with a son, although he gets a little overenthusiastic when it comes to discussing crime scenes and can bore for England on the subject of inefficient internet service providers.

This sturdy former Albany Street desk sergeant is a brisket-faced by-the-book sort of chap who used to be unpleasant and dismissive of the PCU. Blunt but honest, he tends to think with his fists, and had an ill-fated relationship with Janice Longbright. He plays footie for the Met.

The stroppy, difficult, Kawasaki-driving DC comes from a poor South London Indian family, but beneath the (very) hard shell she has a good heart. However, she’s determined to resist the advances of Colin Bimsley, her co-worker.

The fit, fair-haired, clumsy cop is hopelessly in love with Meera, and suffers from Diminished Spatial Awareness, which can make him a liability. His father was also a former PCU member. Colin trained at Repton Amateur Boxing Club for three years, and will only give up trying to date his co-worker if there’s a restraining order placed on him.

The Forensics/Social Sciences Liaison Officer is naturally curious, winning, posh and plum-voiced. Promoted to the position of Chief Coroner at the St Pancras Mortuary, he has relatives in high places who can occasionally help the unit out of tight spots.

These virtually identical West Indian brothers are auxiliary officers who help the detectives in key cases. After Liberty was brutally murdered, his brother Fraternity stepped in to help out at the unit.

May’s granddaughter was severely agoraphobic until resolving issues about her mother, killed by a man the press dubbed the Leicester Square Vampire. Thin and ethereally pale, she joined the unit and was good at making connections, but left after the stress became too much for her. She now lives in Canada near John May’s estranged son.

Everyone thought he was a boy-cat until he had kittens. Named after the first murderer to be caught by telegraph.

The good-natured Maggie runs the Coven of St James the Elder, in Kentish Town. A Grand Order Grade IV White Witch, she is permanently broke but lives to help others in need of her dubious services. She’s part of a network of oddballs, academics and alternative therapists who help the unit from time to time.

The government’s most pedantic civil servant, an outspoken, thick-skinned Home Office Liaison Officer who is thoughtlessly rude and never forgets a grudge. The Peculiar Crimes Unit makes his life miserable, so he tries to return the favour.

Surrounding these main characters are what could loosely be described as Arthur Bryant’s ‘alternatives’, consisting mainly of fringe activists, shamans, shams and spiritualists, astronomers and astrologers, witches both black and white, artists of every hue from watercolour to con, banned scientists, barred medics, socially inept academics, Bedlamites, barkers, dowsers, duckers, divers and drunks, many of them happy to help the unit for the price of a beer or a bed for the night.

BRYANT & MAYWhen I was a child the highlight of the year was to visit Santa Claus at Gamages department store in Holborn. There was always a magical journey to reach him (knocked together with rotating bits of scenery and hand-rocked modes of transport) and when you arrived His Ho-Ho-Holiness would sit you on his knee and ask you if you’d been good all year. Gamages began with a tiny shop front in 1878, but by 1911 its catalogue ran to nine hundred pages. In the early 1970s it was replaced by offices and ‘exciting retail spaces’. It went the way of other great London department stores – Swan & Edgar, Marshall & Snelgrove, Bourne & Hollingsworth, Derry & Toms and Dickins & Jones. The idea for this story came from something that actually happened to me.

AND THE SECRET SANTA

‘I blame Charles Dickens,’ said Arthur Bryant as he and his partner John May battled their way up the brass steps of the London Underground staircase and out into Oxford Street. ‘If you say you don’t like Christmas everyone calls you Scrooge.’ He fanned his walking stick from side to side in order to clear a path. It was snowing hard, but Oxford Circus was not picturesque. The great peristaltic circle had already turned to black slush beneath the tyres of buses and the boots of pedestrians. Regent Street was a different matter. Virtually nothing could kill its class. The Christmas lights shone through falling snowflakes along the length of John Nash’s curving terrace, but even this sight failed to impress Bryant.

‘You’re doing your duck face,’ said May. ‘What are you disapproving of now?’

‘Those Christmas lights.’ Bryant waggled his walking stick at them and nearly took someone’s eye out. ‘When I was a child Regent Street was filled with great chandeliers at this time of the year. These ones aren’t even proper lights, they’re bits of plastic advertising a Disney film.’

May had to admit that his partner was right. Above them, Ben Stiller’s Photoshopped face peered down like an eerie, ageless Hollywood elf.

‘We never came to Oxford Street as kids,’ Bryant continued. ‘My brother and I used to head to Holborn with our mother to visit the Father Christmas at Gamages department store. I loved that place. You would get into a rocket ship or a paddle steamer and step off in Santa’s grotto. That building was a palace of childhood magic. I still can’t believe they pulled it down.’

‘Well, you’re going to see Santa now, aren’t you?’ May reminded him.

‘Yes, but it’s not the same when you feel like you’re a hundred years old. Plus, there’s a death involved this time, which sort of takes the sparkle off one’s Yuletide glow.’

‘Fair point,’ May conceded as Bryant tamped Old Holborn into his Lorenzo Spitfire and lit it.

They passed a Salvation Army band playing carols. ‘“Silent Night”,’ Bryant noted. ‘I wish it bloody was. Look at these crowds. It’ll take us an age to reach Selfridges. We should have got off at Bond Street.’

‘Can you stop moaning?’ asked May. ‘I thought that as we were coming here we could pop into John Lewis and get my sister a kettle.’

‘Dear God, is that what she wants for Christmas?’ Bryant peeped over his tattered green scarf, shocked. ‘There’s not much seasonal spirit in that.’

‘It’s better than before. She used to email me Argos catalogue numbers,’ said May. ‘When I first opened her note I thought she’d written it in code.’

A passing bus delivered them to the immense department store founded by Harry Selfridge, the shopkeeper who coined the phrase ‘The customer is always right’. The snow was falling in plump white flakes, only to be transmuted into liquid coal underfoot. Bryant stamped and shook in the doorway like a wet dog. With his umbrella and stick he looked like a cross between an alpine climber and a troll.

By the escalators, a store guide stood with a faraway look in his eye, as if he was imagining himself to be anywhere but where he was. ‘I say, you there.’ Bryant tapped an epaulette with his stick. ‘Where’s Father Christmas?’

‘Under-twelves only,’ said the guide.

‘We’re here about Sebastian Carroll-Williams,’ said May, holding up his PCU card.

The guide apologized and sent them down to the basement, where ‘O Come, All Ye Faithful’ was playing on a loop along with ‘I Saw Three Ships’ and ‘Ding Dong Merrily on High’. The Christmas department was a riot of fake trees, plastic snow, glitter, sledges, wassail cups, cards, robotic Santas, dancing reindeer, singing penguins, North Poles, Christmas logs, candles, cake-holders, cushions, jumpers and chinaware printed with pictures of puddings, holly, mistletoe and fairies. ‘It’s been this jolly since October,’ said the gloomy sales girl, directing them. In her right hand she held some china goblins on a toboggan. ‘It makes you dead morbid after a while.’

Beyond this accretion of Yuletidiana, a large area had been turned into something called ‘The Santa’s Wonderland Sleigh-ride Experience’. ‘Why do they have to call everything an “experience”?’ asked Bryant irritably. ‘It’s tautological and clumsy. It’s like

Strictly Come Dancing

. The BBC obviously couldn’t decide whether to name it after the old show

Come Dancing

or the film

Strictly Ballroom

so they ended up with gibberish. Two verbs and an adverb? How is that supposed to work? Does nobody study grammar any more?’

‘It’s hard to learn that stuff,’ said May. ‘English is the only language I can think of where two negatives can mean a positive, and yet conversely there are no two positives that can mean a negative.’

‘Yeah, right.’ Bryant turned around. ‘Look out, floor manager.’

Mr Carraway was a man so neatly arranged as to appear polished and stencilled, from the moisturized glow of his forehead and his carefully threaded eyebrows to his shining thumbnails and toecaps. ‘Thank you so much for coming,’ he said, pumping each of their hands in turn. ‘We didn’t know if this was a matter for the proper police or for someone like you, and then one of our ladies said you dealt with the sort of things they couldn’t be bothered with.’