Authors: Jim Ridings

Chicago to Springfield:: Crime and Politics in the 1920s (Images of America (Arcadia Publishing))

Len Small is pictured in 1906. Before becoming governor, he served two terms as state treasurer, and he kept interest money each time. (Herscher Area Historical Society and Museum.)

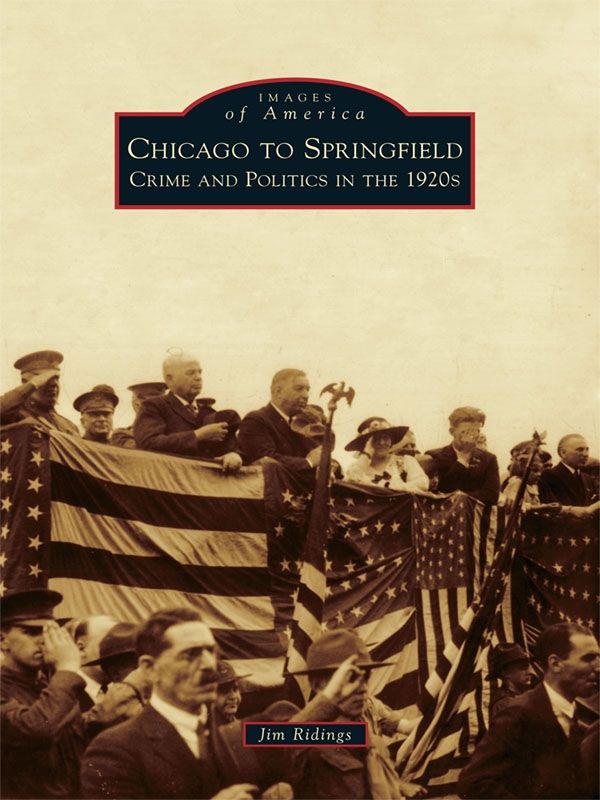

ON THE COVER:

Illinois governor Len Small and Chicago mayor William Hale Thompson share the stage at a public gathering in the 1920s. (Kankakee County Museum Photographic Collection.)

Crime and Politics in the 1920s

Jim Ridings

Copyright © 2010 by Jim Ridings

9781439625736

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010931332

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail [email protected]

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at

www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my wife, Janet, and my daughters, Stephanie and Laura

Thanks go to the Herscher Area Historical Society and Museum; Mary Michals of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield; Betty Schatz and the Kankakee Public Library; the staff of the Kankakee Community College Library; Jeff Ruetsche of Arcadia Publishing; William Furry, executive director of the Illinois State Historical Society; Nancy Fike and the McHenry County Historical Society and Museum; the Dwight Museum; the Kankakee County Museum in Governor Small Memorial Park; and to Nancy (Sawyer) Wagner, Mary Haviland, and Paul Roeder. Thanks also goes to Bill Schaub and Jeff Thompson, managers of the Walgreens stores in Kankakee; Jack and Paula Goodwin of Paperback Reader in Kankakee; the Villages of Campus and Herscher; Campus State Bank; and State Bank of Herscher for their continued support of local history. Thanks to top journalists Rich Miller, Tom Roeser, Chuck Goudie, Steve Sanders, Eric Zorn, Bernie Schoenburg, and others for their reviews and encouragement. Research came from books listed in the bibliography on page 127 and from the microfilm and online files of the

Chicago Tribune

,

Kankakee Daily Republican

,

Kankakee Daily News

,

Time

magazine, and other sources.

The Kankakee County Museum and the Kankakee County Historical Society, other than providing research materials upon request, has not in any other manner participated in the preparation of this publication. It has not been consulted, nor had any part in formulating any interpretations or scholarly arguments that the author has felt justified in forming from any research materials acquired from the artifact, archival, and photographic collections of the Kankakee County Museum.

Unless otherwise noted, the images in this volume appear courtesy of the following:

ALPLM—Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

CHM-DN—Chicago History Museum-

Chicago Daily News

collection

HAHSM—Herscher Area Historical Society and Museum

KCMPC—Kankakee County Museum Photographic Collection

KPL—Kankakee Public Library

KCC—Kankakee Community College

JR—Jim Ridings collection

One might think this book is the story of bootleggers and gangsters in Chicago during the 1920s; it is not. It is the story of the crooked politicians who enabled and aided the bootleggers and the gangsters—allowing small-time gangs to grow into big-time organized crime.

Al Capone became the biggest of all Chicago gangsters. But would Capone have grown as big without Mayor William Hale Thompson, Gov. Len Small, and thousands of other politicians and political workers from city hall to the state house who were anxious to take the mobsters’ money? Chicago police chief Charles Fitzmorris estimated that 65 percent of Chicago’s police were on gang payrolls in the 1920s, not just protecting bootleggers, but pushing the stuff. It also was estimated that the Capone organization took in $100 million a year at its peak in the late 1920s, and $30 million of that went to police, politicians, and anyone else who needed their palms greased. Without the help of crooked politicians and police, Capone might have been just another gang boss, like Bugs Moran, Dean O’Banion, Spike O’Donnell, or Roger Touhy. Without these politicians and police, organized crime might never have become so organized.

There are many famous quotes regarding Illinois politics. Political boss Fred Lundin said it best and most accurately in the 1920s, “To hell with the public and our campaign promises, we’re at the feedbox now!” Chicago alderman Paddy Bauler famously said in the early 1900s, “Chicago ain’t ready for reform.” One hundred years later, it seems it still isn’t.

This book is about crime and politics in the 1920s and takes a special look at the four major political powers of the era: Chicago mayor William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, Gov. Len Small, and bosses William Lorimer and Fred Lundin. The following pages give the background of organized crime not just in the hideouts of the hoodlums, but also in the offices of the elected representatives in city hall and in the capitol, from Chicago to Springfield, in between and beyond.

J. P. Alley’s cartoon in the

Memphis Commercial Appeal

, nearly one hundred years ago, is just as timely today as it was then—no matter what party is doing the singing. (JR.)

ORGANIZED CRIME ORGANIZES

GAMBLING AND GIRLS

While it was Prohibition in the 1920s that really allowed small-time gangs to become major crime families, gangs in Chicago already were very well organized and professional before that era. Criminals started organizing almost from the time Chicago was founded. Gambling and prostitution flourished from the start, and they were the first industries to rebuild after the great fire of 1871. Michael McDonald became the king of the gambling rackets in the 1880s, and the Levee District in the First Ward became a cesspool of prostitution, gambling, and other vices by the 1890s. Mont Tennes followed McDonald as the head of the gambling rackets, while “Big Jim” Colosimo took organized crime to a higher level.

Chicago’s First Ward aldermen “Bathhouse John” Coughlin and “Hinky Dink” Kenna solidified the partnership between crime bosses and politicians in the 1890s. Their criminal-political machine was based on graft and protection money from the saloons, brothels, and gambling halls of the Levee. To hold onto their power, Kenna introduced “chain voting,” where premarked ballots were taken to polls by election workers who continued until enough ballots were cast to make their candidate a winner.

Coughlin and Kenna were succeeded by a long list of Mob-connected politicians, continuing to the present era. A recent graduate was First Ward alderman Fred Roti. His father, Bruno “the Bomber” Roti, worked for Al Capone. The FBI called Fred Roti a made member of the Mob who ran the rackets, bribed judges, and eventually went to prison. Roti died in 1999 and is buried in Mount Carmel Cemetery, not far from Al Capone’s grave.

Bathhouse John (above, left) and Hinky Dink Kenna (above, right) helped Big Jim Colosimo get his start. Colosimo owned a famous nightclub where celebrities, politicians, and others from Chicago’s elite gathered. Colosimo and his wife, Victoria (whom he dumped for showgirl Dana Wynter, at left), also owned as many as 200 brothels, many of them in the Levee District. He collected from the brothels to pay off the politicians and police. Colosimo’s pimps and prostitutes worked the polls on election days. The brutal Colosimo also practiced white slavery, luring innocent women into forced prostitution. (All KCC.)

Johnny Torrio came to Chicago from New York when Colosimo called him. Torrio became the brains of the criminal organization. Big Jim was content with his prostitution and gambling and did not want to expand into the new bootlegging racket provided by Prohibition in 1920. Torrio had Colosimo killed; Al Capone was likely the gunman. (KCC.)

Torrio brought in his own protégé from New York—Al Capone. With Torrio’s brain and Capone’s muscle, they became the dominant gangsters in Roaring Twenties Chicago. Capone got his nickname “Scarface” after being slashed in a barroom brawl in New York but preferred friends call him “Snorky,” meaning sharp or elegant. (KCC.)

After Torrio was seriously wounded in 1925 by gangsters Bugs Moran and three others, he semi-retired and turned over the command of the organization to Al Capone. Capone found a friend and ally in Mayor “Big Bill” Thompson. (KCC.)

When scandals forced Mayor Thompson to withdraw from the race in 1923, William Dever (pictured) was elected mayor. Dever’s crackdown on gangs had a minor impact on crime in Chicago, but it did cause Capone to look for another sanctuary. Capone went to suburban Cicero and Forest View and took over those towns. Any opposition in there was met with beatings and intimidation. Capone needed his own village officials in place, and he put his efforts into the 1924 municipal elections. (KCC.)

Edward Vogel (pictured), along with “Big Ed” Kovalinka and gangster Louis LaCava, picked the men who would run for office in Cicero and Forest View. Kovalinka was precinct committeeman and a protégé of Gov. Len Small. They appointed William “Porky” Dillon, a thug pardoned by Governor Small, as Forest View’s police chief. Dillon also was a bagman in the selling of pardons by Governor Small. Together they helped deliver Cicero to Capone and his hoodlums. Vogel went on to be an important figure in the Mob’s gambling rackets. (KPL.)

Election day 1924 saw gangsters patrolling the streets with guns and beating election workers and police. Capone’s candidates won the election, but five people were killed that day, including Frank Capone, in a shoot-out with police. (KPL.)

Chicago’s most infamous gang murder was the St. Valentine’s Day massacre in 1929, when Al Capone sent his gunmen to kill rival George “Bugs” Moran’s men in their garage hideout on North Clark Street. Seven people were slaughtered. Capone’s assassins, posing as Chicago police, lined Moran’s men against the wall and opened fire. Moran was on his way there when he saw the “police” arrive, so he stayed back and avoided the carnage. (KCC.)

No one was arrested for the St. Valentine’s Day murders. Rumor linked gangsters “Machine Gun” Jack McGurn, Frank Nitti, and Gus Winkeler to the planning of the crime. The only man positively connected to it was Fred “Killer” Burke (pictured). When he was arrested for the murder of a Michigan policeman, a machine gun found in his home was proven to be one used on St. Valentine’s Day. When he was arrested, Burke was living with Viola Ostrowski Brennenman, a Kankakee woman. (KCC.)