Read Daily Life In Colonial Latin America Online

Authors: Ann Jefferson

Daily Life In Colonial Latin America (8 page)

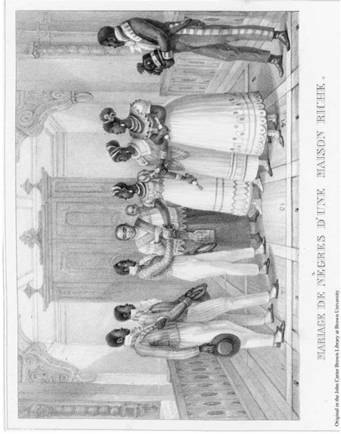

Mariage de nègres d’une maison

riche

(marriage

of slaves belonging to a wealthy household) by Jean Baptiste Debret dated 1835.

Although Brazil was no longer a colony at this time, slavery would remain

firmly in place for several more decades. This drawing shows several black

couples being formally married by a priest in a chapel.

Casta Families

Among the non-Indian lower social groups, Christian

marriage was uncommon. The norm was cohabitation. One reason was the prohibitive

cost of marriage. Another was the lack of property to pass on. The landless

population, those living and working on haciendas, found little reason for

Christian marriage since there was no property to protect for future

generations. Without this hold over their children, parents had little control

over young people’s freedom to choose their partners and settle down without

benefit of marriage. The main reason to marry formally was to climb the social

ladder by practicing this most important rite of Christianity and European

values. Peasants who did choose to marry might do so after setting up a

household and acquiring some property. Or their reasoning might be to lift

their children out of the stigmatized category of illegitimacy. Frequently,

marriage applications state that the young woman is pregnant or that the couple

already has one or more children, indicating a connection even in this marriage-shy

population between having children and seeking formal marriage.

The church did not succeed in exerting the same control

over these families that it had over the highest and lowest social groups. In

urban areas, the church was more concerned with ministering to elite families

than to the racially mixed working population, and in rural areas, villages

were scattered widely across the land and priests were few and far between, and

thus very overworked. Although they struggled to bring their wayward sheep into

the marriage fold, it was an uphill battle, given the broad acceptance of

common-law marriage among the casta population.

The primary limitation on finding a partner was the small

number of families living on the hacienda or in the village. Marriage between

first cousins—a frequent occurrence among the elite, as discussed above—was

also fairly common in the casta population, although for different reasons. In

the latter case, cousins married not to protect family property and social

status, but because of the difficulty of finding a partner of the right age in

a small community where most of the population was related.

Among peasants who owned their own land or had rights to

common village lands, the patriarchal family might exert as much control over

the choice of their child’s marital partner as did elite parents. When he

married, the young man received his portion of his father’s land and space in

his father’s house, generally part of the common space, although an addition

might be added later; the bride went to live with her new husband’s extended

family. Some peasant families even employed the dowry as a symbol of their

upcoming contract, although its size would not reach that of the lavish dowries

provided to daughters of the elite.

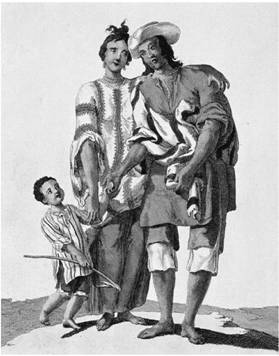

This

engraving of a casta family by Juan de la Cruz from 1784 depicts a family of

the French Caribbean. Casta paintings, many of them produced in 18th-century

Mexico, were prized by European collectors fascinated with the exotic racial

categories depicted by artists interested less in representing colonial reality

than in conveying messages about the supposed social consequences of racial

mixing.

BIGAMY

What are we to make of the fact that statistically the

casta population was least likely to marry and also the most likely to marry

twice? Once again, the answer probably lies in the relative lack of control the

church exercised over the lives of these people and, of course, the growing

size of this population during the colonial period. In addition, the frequency

of bigamy in this group may be simply an indication of its more freewheeling

lifestyle and lack of enthusiasm for monogamous, lifelong Christian marriage.

The Inquisition devoted considerable energy to

investigating bigamy. Although the main business of the Inquisition in the

American colonies was to ferret out “New Christians” who might be secretly

practicing Jewish rituals, a phenomenon discussed more fully in chapter 6, the

institution concerned itself with a wide variety of violations of Christian

principles. Bigamy ranked high on the list of infractions. While Islam

permitted polygamy, the Roman Catholic Church treated bigamy as both immoral

and heretical. One way that Catholics differentiated themselves from the Muslim

culture that had dominated the Iberian Peninsula for hundreds of years was by

establishing marriage as an exclusive relationship between one man and one

woman.

Nevertheless, some people of the lower social groups

committed bigamy, and since the punishments doled out were severe, it makes

sense to ask why they did it. Usually they were men, many of whom had found it

necessary to leave one area and take up residence in another. This might happen

because a man found himself on the wrong side of the law, but more often simply

for employment. The assumption under the colonial patron-client system— the

traditional form being a plantation owner, or

hacendado,

with a large

household of dependents and servants, as well as many laborers who relied on

him for work—was that every member of the working classes needed a

patrón,

who

provided employment and credit, as well as protection for his workers in court

should that be necessary. The patrón served as a kind of insurance policy. The

only flaw in this system was that there were not enough positions for all the

laborers who needed to attach themselves to a master. As a result, many men of

the popular classes found it necessary to move from time to time and look for

work. The difficulty of travel would then prevent their returning home regularly.

Socializing with residents in the new location, along with the impossibility of

living alone, might lead to new couple relationships. The true vagabond would

not need to marry, of course, but the footloose and fancy-free life did not

appeal to the bigamists; they wanted to settle down and have a home. The fact

that they married a second time seems to indicate their desire to abide by,

rather than to violate, the social rules. Sometimes the authorities had a hand

in the decision to marry, since the local priest and government functionaries

were likely to appear at any time of day or night in their unceasing efforts to

end cohabitation. Once the authorities were in the picture, marrying headed off

unpleasant legal consequences, until bigamy was discovered, of course.

CONCLUSION

Like everything else in colonial Latin America, the family

looked different at different levels of the social structure. The church had

considerable success in enforcing Christian marriage as the portal to family

life for those at the two levels where the church exercised most power: among

elites and the indigenous people. Among the casta population and the community

of enslaved workers, family formation was less orderly. The existence of a

racially mixed population was always inconvenient for the Spanish crown and

never officially acknowledged. As a result, people at this level had

considerably more latitude in choosing a partner, as well as in the matter of

whether or not to formalize their relationship. Family formation among the enslaved

population was of less interest to the church, partly because insisting on

formal marriages in this case would have brought the church into conflict with

some of its most important donors. It is important to note, however, that the

frequency of slave marriages by a priest was often surprisingly high, as the

evidence from a frontier area of Brazil shows. This evidence indicates a

commitment on the part of owners to regularizing the laboring population and an

attempt by the workers themselves to seek shelter in the bosom of the

church-approved family.

Families were viewed as the basic building block of

society. An orderly hierarchical society depended on maintaining established

social levels, and this system in turn depended on guiding the process of selecting

a partner. Elite parents and the church exerted their influence over young

people at the highest social level as a way of protecting and perpetuating

elite patriarchal families and their property. In general, Indians married

other Indians, and this was certainly encouraged, partly to facilitate the

collection of tribute from that population. While things were a lot less

orderly at the level of middle groups, the record shows a clear preference for

Christian marriage and legitimization of the offspring among those aspiring to

climb the social ladder; the documentation also shows their imitation of elite

practices like the dowry. Enslaved Africans, and those free people who chose

enslaved partners, had very little control over their family life, married or

not. While slave owners seem to have made some effort to keep couples together,

that may have been more for the sake of order among the working people on the

estate than for humane reasons. Despite legal protection for marriage among the

enslaved, the adjudication of a will or the whim of an owner often separated

even formally married couples. Their children were normally considered future

laborers, rather than members of nuclear families, and distributed according to

the best interests of their owners.

The reader may note here that the focus in this chapter on

marriage as a contract between families and the basic building block of

colonial society has told us little about the nature of love or affection in

that society. For example, an examination of the institution of marriage

provides only a partial view of colonial sexual practices and their meaning to

participants. Historical documents show that people frequently employed their

sexuality outside the institution of marriage, in spite of the position of the

Roman Catholic Church that sex was sinful except when its purpose was

procreation within marriage. The next chapter addresses this extramarital

dimension of sexuality and affective life at greater length, including both

heterosexual and homosexual relationships and the sex lives of priests sworn to

celibacy.

2 - LOVE, SEX, AND

RELATIONSHIPS

INTRODUCTION

Love

and sexual attraction are among the areas most inaccessible to the student of

history. The emotional life of our subjects is often hidden from view. It does

not emerge explicitly in statistics, trials, wills, or other public documents

historians normally use to create a picture of life in the past. It seems

clear, however, that people are sometimes drawn to mates who might not be

suitable or socially convenient for a variety of reasons: the prospective mate

might be promised, or already legally joined, to someone else; might be from a

different social group; might not reciprocate the feelings; might be of the

same gender; or might be a religious worker bound by a vow of chastity. In

short, attraction to another is part of life and a part that does not respect

social rules. In the previous chapter, it became clear that marriage in

colonial Latin America was a contract between families, managed by the

authorities of the religious state. While there were exceptions to the rule,

generally marriage had little to do with love or attraction.