The Broken Lands (16 page)

Authors: Kate Milford

“Oh, no,” Sam muttered. “Don't do it, kid.”

Ambrose nodded sadly. “Of course he took it down, but only to see it better. And of course, that's when Jack woke up and screamed at the boy to give it back, and in his panic the boy dropped the necklace into what remained of the fire.”

“Rosin is a kind of pitch,” Jin said softly. “Pitch burns.”

Ambrose nodded again. “Jack dove and managed to save it before the piece burned up entirely, but the damage was done. He turned on the trembling boy, who was crying his apologies, and ordered him from the house.

“âBut what if it's still out there?' the boy asked.

“That, of course, was the question. Jack looked at the strange child who wore such terror on his small face and for a moment he almost relented. But he was too far gone, and in the end, his twisted anger and hurt won out.

“He opened the door and the boy, who knew perfectly well that the damned thing was still out there seeking him, walked out of the cabin, shaking all over.

“It was upon him before Jack could shut the door.

“The boy dropped to his hands and knees with a shriek. It was as if something huge, something unseen, had come flying at him from behind and knocked him flat. Then the boy was upright again, but plainly not under his own power. He flailed violently back and forth and from side to side, feet occasionally leaving the ground, entire body occasionally beingâhow else to put it?â

blotted out,

as if some larger creature had passed between the boy under attack and the man watching.

“Jack managed to pull himself together long enough to realize he ought to go for his gun. By the time he had gotten it and come back to the door, the golden-eyed boy was dead. The last thing Jack saw was his shredded body sliding along the ground toward the woods, dragged by the unseen thing that had chased him there. And Jack made his last wish: that anyone else who touched that pendant would feel the full weight of all his loss and all his sadness and all his loneliness, as well as all his horror and guilt for what he had done to the boy. And that was the autumn.”

Despite his skepticism about the story itself, Sam discovered he was shocked and horrified. He glanced at Jin. She held her fists curled tightly in her lap, and her fingers were so tense that a little network of shiny scars on her hands that Sam hadn't noticed before stood out white against her skin.

“Winter came and went and came again. The death of the strange boy marked Jack's cabin as an evil place, and there were no roamers desperate enough to venture there any longer. Years passed and Jack lived on, alone and unaging as he waited for the woman to return and suffered the memory of the boy's death over and over. Perhaps his long life came from his dealings with the uncanny roamers; perhaps the world of men had just forgotten him as completely as he had forgotten it.

“But the otherworld had not forgotten Jack and what he had done. Poor hospitality was bad enough, but there were very few children among the uncanny, and the death of the boy with the golden eyes was something they could not forgive. They watched Jack's life lengthen as if he had no intention of dying, and finally they decided that if he would not die like the mortal he was, someone would have to go and carry him to Hell where he belonged.

“The first one turned up in the winter. When Jack opened the door, he found a man in a striped suit waiting there. âJack, I'm here to carry you to Hell,' the man said, âand I'm not taking no for an answer. Get your things together and let's go.'

“Jack stared at the man in the suit for a long minute. Then he laughed. âFine. I guess it's about my time. Come on in while I pack. There are some blankets there if you'd like to warm up.'

“âDon't mind if I do,' the man said. And he went straight to where the blankets sat on a chair by the fire. Jack stood there and laughed and laughed while the blanket the man had reached for clung to his fingers, burning them and refusing to be let go, no matter how the stranger shook his hands and howled.

“âI'll set you free,' Jack laughed, âbut I'm certainly not going with you to Hell.' What could the fellow do but agree? So Jack ordered the blankets to stop their torture and the man in the suit slunk out of the cabin and into the woods.

“The next one came in the summer. This was a bigger man, shaggy-headed as a bear. âI'm here to carry you to Hell,' he growled when Jack opened the door, âso get your things together and let's go. And I know all about your cursed blankets, so don't bother trying that trick on me.'

“This time Jack didn't laugh. He took a deep breath and nodded. âI can see I'm not going to be able to change your mind,' he said sadly. âCome on in while I pack.'

“âNo, thank you,' said the shaggy-headed man. âI'll wait right here. Make it quick.'

“âWell, I suppose there isn't really much I need,' Jack admitted. âTruthfully, the only thing I really care about is that rose vine. It reminds me of someone I used to know. Since you're right there, break me off a branch of roses and I'll be ready to go.'

“The shaggy-headed man was so pleased with how well Jack was cooperating, he didn't bother to wonder about the strange request. He reached right into the roses, and immediatelyâtoo quickly for the man to escapeâthe vine wrapped him in its thorns. The stranger screeched in pain while it twisted and tightened, and Jack just laughed and laughed.

“âI'm not going with you,' Jack said finally. âI'll let you go, but then off with you and leave me in peace.' The man held out as long as he could, but in the end there was nothing for him to do but agree.

“The last one came in the autumn, and it was a girl. When Jack opened the door and found her there, he nearly fainted dead awayâshe was the very image of the golden-eyed boy, only her eyes were the silver of the winter moon.

“âYou have worn out your welcome in this place,' she told him. âCut me with your thorns, burn me with your blankets, it makes no difference. There is no torture you can show me that I don't already feel without my brother. I am here to carry you to Hell or tear you to pieces myself.'

“Jack looked at her and knew that she was telling the truth. âFine,' he said. âBring me my necklace, the one by the hearth, and I'll go with you willingly.' And I think there was a part of him that hoped this last ruse would fail. He held his breath as the girl with the silver eyes crossed the cabin and took hold of the rosin pendant.

“Her scream was worse than any sound he had ever heard, full of more pain than he would have believed possible. It was the sound of murder witnessed; it was the sound of humanity dying; it was the sound of hope frozen and thrown against a rock to be crushed like an icicle. It was everything Jack had wished. Before his eyes the girl was rapidly going mad with anguish. It was too much to witness, even for him.

“âStop,' he shouted. âStop, and set her free!' But he had forgotten to include that bit in his wish, and all he could do was try to hold her down and keep her from hurting herself until she reached a momentary calm, like an eye in the storm of torment. The girl stared at him with her red-rimmed silver eyes. âI see now,' she said in a voice broken by screaming. âYou are already in Hell.' And then she flung him aside like a rag doll as the pain and agony began to build in her body again. She staggered out of the house screeching, leaving Jack alone with his precious possessions. For a long time, he heard her ravaged voice echoing through the trees.

“More years went by, and at last Jack began to tire of his long life. The woman with the violin was clearly never coming backâthere was no way to know if she was even alive. Worse, he had the death of the boy with the golden eyes and the madness of his silver-eyed sister on his conscience, and these memories never stopped tormenting him. So finally he packed up his things, put the pendant around his neck, cut a rose from the vine for his lapel, and went in search of Hell for himself.

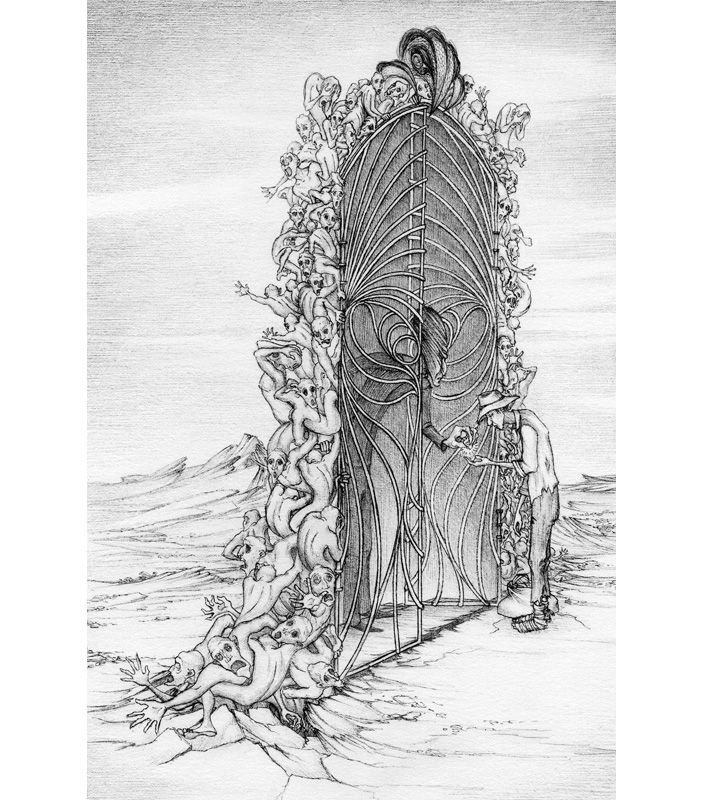

“From time to time, he encountered other strange roamersâfor naturally, that is what Jack himself became the second he started out on the roadâand after all the trouble he had caused, they were glad to help him find his way. But when he at last found his way to the Gates of the Underworld and rang the Infernal Doorbell, something impossible happened.

“The Devil himself came to the door, looked Jack over as if he were some form of livestock, and pronounced these words: âNo, I don't think so.' Then the Devil paused, fished about in his waistcoat pocket, and held out his hand. In it was a live coal.

“âTake this,' he suggested, âand go find your own place. I suppose you know Heaven isn't going to let you in, either.' And with that, the Gates of the Underworld clanged shut in Jack's face.

“And that,” Ambrose finished, “is how Jack came to be wandering the earth, looking for somewhere to start his own place.”

“Stepped on a pin, the pin bent, and that's the way the story went.” Tom lifted his glass. “That's the proper way to finish a tale like that where I come from.”

“That's a story,” Sam protested after a long moment's silence. “That's not real. It isn't possible.”

“I told you you'd have a hard time believing it,” Ambrose said. “A city is chaotic, but it's at least predictable. The country is wide and strange, and full of wonders that have to be seen to be believed. This is who is meant by Jack Hellcoal.”

“So the message,” Mapp said grimly. “The words that were on the wall. They said

Claimed by blood for Jack Hellcoal

. What is it he's claiming, exactly?”

“Well,” Ambrose said thoughtfully, “I think you have to consider the worst-case possibility, Mr. Mapp. That he's decided on New York.”

Then the Devil paused, finish about in his waistcoat pocket, and held out his hand.

Then the Devil paused, finish about in his waistcoat pocket, and held out his hand.Â

Sam stared. “He's . . . decided on New York for what? For his own . . . what, his own personal Hell?”

“Looks that way,” Ambrose said, draining what remained in his glass.

Jin turned her glass in circles on the tabletop. “How does it work? Making a place into Hell?”

Ambrose shrugged. “No idea.” He looked at Tom, then at Mapp. “You?”

Mapp shook his head. “Nope,” Tom said thoughtfully. “But I can't say as I think it sounds like a good thing for the folks who already live here.”

Silence fell over the table.

“He must be stopped,” Ambrose said finally. “He absolutely must. You understand, this isn't about New York. I like New York, but there's more at stake than that.” He looked at Tom. “That's true, isn't it?”

The old man nodded. “The country isn't in what you'd call a safe place. Folks are angry, still. Folks are scared, and folks feel like punishing each other, and I don't think many of 'em are clear about what they're mad for. They're just mad.”

“That's because they're the

other

kind of mad,” Ambrose muttered. “All of them. They're less than a score of years removed from the worst thing that has ever happened to this country, and frankly, a lot of things that many of us hoped a Union victory would change went right back to the way they were. The number of lynchings this year . . . the strikes, the bombings . . . the number of people who are out of work . . . and a lot of people seem to be working rather diligently to make sure Emancipation turns out to be a change in terminology rather than a new life for men like Tom.” He looked at the old guitar player. “Would you agree?”

Tom sighed. “Being free is better than the alternative. But just saying the word isn't enough. There's a lot of places in the country where folks will still do mighty nasty things to a body, free or not.” He rubbed a hand across his face, which wore an expression that reminded Sam a lot of the haunted gazes of some of the other soldier-guests of the hotel. “So many people died for us to be able to have a right to that word,

free

.”

Ambrose nodded. His eyes were glazed over in recollection. “It was just bodies falling,” he murmured. “Whatever got you there in the first place, in the end it was bodies falling and dying long, slow deaths. They weren't even people. They were just bodies, bodies that fell and foamed and bled and froze and starved and died. And no one has forgotten, or forgiven, a moment of it.”

He smiled thinly at Sam. “The point is, the country is angry and afraid and I swear to you, not one city, not one town is safe from the possibility of exploding into violence at the slightest touch. Nothing would provide a swifter impetus back into chaos than some kind of inexplicable terror erupting in a place as visible as New York. Frankly, I don't think I'm alone in believing the United States would plunge headlong into panic at far less. Just think about what happened only last month with all the railroad strikes. Dozens and dozens of people dead. Whole streets, whole districts burned to the ground. Hell, if a strike in Pittsburgh can almost start a war, wellâ” Ambrose shook his head and shuddered. “This country is fragile. If New York or any city of the North or South falls . . . What we're discussing would tear this country to pieces once and for all.”