The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (37 page)

Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

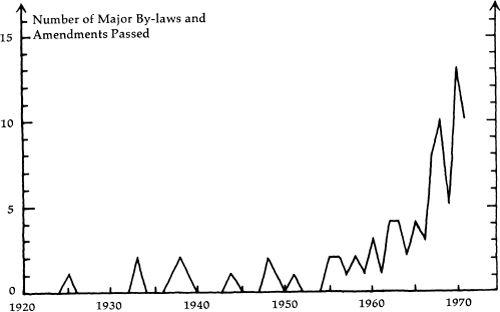

For comparison, here is another graph for ninety communities in Canada, which shows that recent concerns about noise extend also to cities and towns with smaller populations.

At this point it is advisable to point out that cities with no anti-noise legislation should not necessarily be considered backward; perhaps they are just quieter. For instance, while the principal cities of India possess no anti-noise legislation, sound level readings taken in numerous districts of Bombay at night were all significantly lower than the upper limit advocated by Norway for residential districts at night.

z

Although community noise legislation around the world is various, certain subjects reappear with predictable regularity:

shouting or creating a disturbance in public;

street and house music;

loudspeakers, radios, etc.;

noisy animals;

unmuffled motor vehicles;

noisy industry in residential areas.

While these are common to many parts of the world, the stress is often different. Thus while in northern countries dogs prove to be a special nuisance, in Latin America it is radios and loudspeakers. In many Latin American cities this is the only item covered by the noise by-law, which is usually aimed at restricting the use of loudspeakers by vendors and outside business establishments. (Venezuela appears to be unique in prohibiting music in busses and taxis if passengers find it objectionable.)

Restrictions against blowing car horns are found in numerous by-laws around the world although the enforcement of the legislation varies enormously. While cities like Tunis restrict the blowing of horns to “un ou deux coups brefs … en cas d’absolue nécessité seulement,” when we had researchers count the number of horns sounded at main intersections in several of the world’s capitals, the Middle East appeared to be the most tolerant of car-horn noise. Here are the hourly averages for a few different cities:

| | Moscow | 17 |

| | Stockholm | 25 |

| | Vancouver | 34 |

| | Utrecht | 37 |

| | Toronto | 44 |

| | Sydney | 62 |

| | Vienna | 64 |

| | Amsterdam | 87 |

| | London | 89 |

| | Tokyo | 129 |

| | Boston | 145 |

| | Rome | 153 |

| | Athens | 228 |

| | New York | 336 |

| | Paris | 461 |

| | Cairo | 1150 |

These counts were done in 1974-75. Our method was to count all audible horns at an intersection over a period of nine hours on a typical weekday. Of special interest is the fact that previous counts done at the same locations in London and Paris yielded far fewer horns. In fact, the number had about quadrupled in both cities in four years! Could this be part of a larger pattern of increase?

Our civic noise legislation list distinguishes between those communities possessing qualitative and quantitative legislation. It also shows that a considerable number of communities are expecting to adopt or are actively studying some form of quantitative legislation. As this appears to be a trend, at least among technologically developed nations, it calls for a comment. Quantitative legislation shifts the burden of investigation and proof onto the civic administration, which is an encouraging change, for the difficulty with qualitative legislation has always been to prove anblegation of noise in court. Nevertheless, quantitative legislation is difficult and costly to supervise, for expensive equipment must be purchased and it must be operated properly by trained staff.

Two approaches to the quantification of sound measurement are currently employed. The first, which is favored in such parts of the world as Japan, Scandinavia and Australia, is to establish acoustic zones in the community (residential, commercial, industrial, etc.) and to fix general sound levels for each zone for particular times of the day and night. A second method is to set limits for particular offensive noises and to concentrate on keeping them under control. This method is preferred in Canada, the U.S.A. and parts of Europe and South America. Little standardization exists from country to country or even from community to community in the same country. For example, among the seven Canadian cities with quantitative limits for automobiles in 1972, the permissible level ranged all the way from 80 decibels at 20 feet (Burnaby, B.C.) to 94 decibels at 15 feet (Toronto, Ontario). In fact, after a careful investigation of quantitative legislation from many countries, one is forced to conclude that there is every bit as much capriciousness involved in its formulation as in the other kind.

The difficulty is that while established levels may be able to cope with physically destructive sounds, they do not relieve the problem of psychologically distressing nuisances. This is an area in which too little research has been conducted, and in any case it is hardly likely to lend itself to such easy quantification. It is for this reason that the most practical anti-noise legislation for the present era should contain both quantitative and qualitative provisions, though as human nature seems always disposed to an either-or approach to problem-solving, we will probably witness an erosion of the qualitative in favor of the quantitative, for the latter better suits the technocratic mind.

How the Study of Noise Legislation Reveals Cultural Differences

Noise by-laws are not created arbitrarily by individuals; they are argued into existence by societies. Hence they can be read to reveal different cultural attitudes toward sound phobias. For instance, along with articles dealing with well-known noise sources, the city of Genoa (Italy), in its

Regolamento di Polizia Comunale

(1969), identifies some unusual problems. Article 65 states that from 9 p.m. to 7 a.m., shutters must be opened and closed as quietly as possible. A keynote for the European, the shutter is a soundmark for the outsider. In this connection, too, I am reminded that in Étienne Cabet’s nineteenth-century Utopia,

Voyage en Icarie

, the author describes the wonderful invention of noiseless windows with which each Icarian’s house is fitted. Article 67 of the Genoese regulations places restrictions on the noise of furniture moving between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m.—a matter which may cause some puzzle mentuntil an Italian explains that often heavy work such as moving is carried on at night to avoid the summer heat. Article 70 contains the customary proscription against street music and article 73 explains that Bocci (Bowls) must not be played after midnight. It is surprising to find specific games mentioned as sources of noise, but outdoor bowling is frequently mentioned in the by-laws of European cities. In Luxembourg it is prohibited to “jouer aux quilles” between 11 p.m. and 8 a.m.

A curious piece of legislation, found in Germanic countries but not elsewhere, is directed against the beating of carpets and mattresses. This was encountered in Switzerland (page 190). In Bonn (Germany) “the beating of carpets, mattresses or other objects is only tolerated on weekdays between the hours of 8 a.m. to 12 noon and additionally on Fridays from 3 p.m. to 9 p.m.” In Freiburg (Germany) the law is the same but the times are slightly different: weekdays 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 3 p.m. to 9 p.m.

aa

The siesta is a time of reduced energy and many by-laws restrict noisy activities during this period. It is interesting, however, to observe how the siesta expands as one moves south into the stronger sun. In northern Europe it is generally two hours: 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. In Italian cities it often extends from 12 noon to 4 p.m.; but in North Africa it runs to 5 p.m. Typical is this by-law from Tunis: “Between the hours of 10 p.m. and 8 a.m. during the whole year, and between 12:30 p.m. and 5 p.m. from June 1 to September 30 inclusive, it is forbidden to produce or permit to be produced, noises which may disturb the tranquility of the neighbourhood.” Interesting are some of the noises identified in this by-law: “This prohibition applies notably to noises produced in the street or on private property by automobile horns, musical instruments, testing motors, exhaust noise, trumpets employed by gasoline salesmen [!], whistles or cries of ice-cream vendors, or any other calls.” It was this last sound that Albert Camus recalled especially when he reflected on life in North Africa: “… one incident stands out … I heard the tin trumpet of an ice-cream vendor in the street, a small, shrill sound cutting across the flow of words.”

Certain strong but quite vernacular noises may be considered sound-marks—albeit negative ones. For instance, among the most complained of sounds in the city of Essen (Germany) is the restaurant noise of pounding veal foi schnitzels. In Hong Kong a principal source of noise complaints is the sound of “malh jons parties.,he slapping together of mab-jong tiles is also characteristic of the Chinese districts of Vancouver and San Francisco, where it is enjoyed by the tourists.

India is becoming concerned about the noise of air-conditioners at night in the fancy tourist hotels now being built, a problem which has already attracted the largest number of public complaints of any noise in the affluent city of Chicago. In places where there are such hotels in India the sound level was found to be 15 to 20 decibels higher at night.

In Mombasa (Kenya), some of the most common noises are “tin-beaters, drum-beaters, blacksmiths and charcoal-stove makers"; while in the port city of Auckland (New Zealand), a major source of complaint is “backyard panelbeating and boat building"—and there is a by-law designed to prevent it from taking place at night. In Rabat (Morocco) one of the chief noises is family reunions, while in Izmir (Turkey) it is unruly behavior at bus terminals (one has to have visited Turkey to appreciate this) and the matter is dealt with in a rather whimsical piece of legislation: “In bus terminals and parking lots proper behaviour is expected. Any case of noise which may disturb the public—for instance, shouting, fighting, etc.—is subject to a penalty. Any claim that the act was a joke will not change the consequence, which is a 50 Turkish Lira fine.”

By-laws also reveal the different states of development of societies. While in 1961 the city of Melbourne (Australia) repealed an ancient bylaw prohibiting “the ringing of auctioneer’s bells,” because it was no longer necessary, in the same year Manila (Philippines) found it necessary to introduce legislation against such activity: “No bell or crier or other means of attracting bidders by the use of noise or show, other than a sign or flag shall be employed.”

While legislation against loudspeakers and amplified music is common around the world, it is important to note the exemptions worked out by various societies. For instance, Manila, while prohibiting the operation of outside radios and phonographs, retains them for “restaurants, refreshment parlors, beauty parlors and barber shops … from 7 a.m. to 12 midnight.” Vendors of “newspapers and peddlers of ice cream, fruit, candies, confections and sweetmeats” are also permitted the use of a megaphone or magnavox from 5 a.m. [!] to 11 p.m. Another ordinance in Manila states that the prohibition of amplified sound shall not apply to “any house or place where the sacred passion of Christ is recited or sung during Lent… and in cases of important international or national radio events.”

Keeping Sunday quiet, which was a special concern in Switzerland, is by no means a concern of all Christian countries. In San Salvador, for instance, the following schedule to control the use of loudspeakers shows that religious holidays are to be regarded as festive occasions. Loudspeakers are permitted at the following times:

Monday to Saturday: 12 noon to 10 p.m.,

Sundays and Holidays: 8 a.m. to 10 p.m.,

December 24 and 31: 8 a.m. to 5 a.m. of the following day.

We have seen from Chicago how church bells are beginning to become a source of complaint—as was predicted earlier in this book. The same sound is also beginning to cause concern in Germany, and in Luxembourg it has been mentioned as a source of growing complaint. In fact a number f municipalities have already enacted legislation restricting the times when church bells may be rung. Manila restricts them to no more than three minutes per hour during the day and prohibits them entirely between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. In Chiclayo (Peru) they are prohibited between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. In Genoa they are to be silenced on complaint and Hartford (Connecticut) “prohibits the ringing of bells attached to any building or premises which disturbs the quiet or repose of persons in the vicinity thereof.”