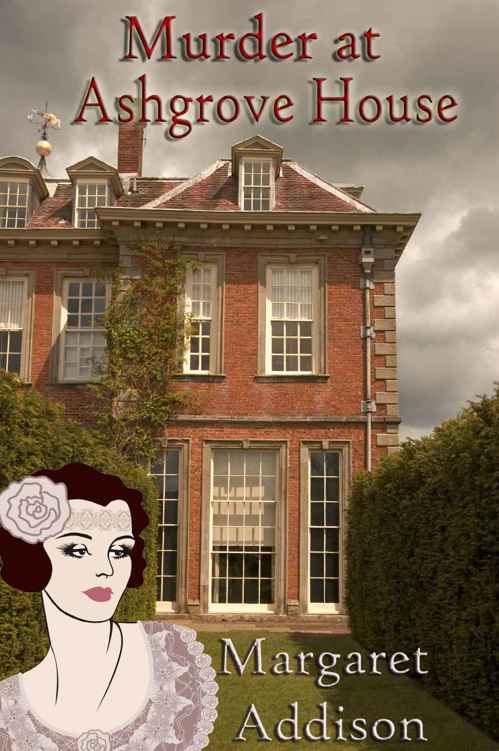

01 - Murder at Ashgrove House

Read 01 - Murder at Ashgrove House Online

Authors: Margaret Addison

MURDER

AT

ASHGROVE HOUSE

by Margaret Addison

A Rose Simpson Mystery

Copyright

Copyright

2013 Margaret Addison

All rights

reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by

any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission

from Margaret Addison except for the inclusion of quotations in a review.

This book is

a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are the product of

the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual

events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

‘Oh, William, I am so frightfully worried about our house party this

weekend,’ said Lady Withers floating into the library at Ashgrove House, where

Sir William was seated on a Chesterfield sofa reading

The Times

. ‘I’m

afraid that it’s going to be a disaster. I’d invited all the right people,

that’s to say the ones that go together so to speak, but now I’m awfully afraid

that it’s not going to work at all.’

‘There, there, Constance my dear, it can’t be that bad,’ said Sir

William, soothingly. Such an announcement had not worried him unduly for he was

well used to his wife’s exaggerations. Indeed, to her annoyance, as far as Lady

Withers could tell he was carrying on reading his newspaper.

‘Darling, I’m being absolutely serious.’ Lady Withers perched herself

beside him on the sofa and fought with the newspaper until, with a sigh he

closed it and put it on the coffee table resigning himself to giving her his

full attention.

‘What can you mean, my dear, I can’t imagine anything nicer than having

young Lavinia down for the weekend. It seems an age since we last saw her.’

‘It

has

been ages, William. She’s been working in that awful

little dress shop. How she can possibly bear it, I don’t know. I don’t think

they even usually give her Saturdays off, can you imagine. But you know what

young girls are like these days. I blame it on the war, don’t you, all that

ambulance driving and men’s jobs, not of course, that Lavinia did any of those

things, being just a child at the time, but still it made women feel they could

do all sorts of things and I expect it’s still in the air. Now, what was I

saying? Oh, yes, it’s not Lavinia I’m worried about, because of course I want

to see her. It’s who she’s bringing down with her that worries me. Of course,

when she asked me if she could bring down a friend, I had no idea that she

meant a girl who worked in the shop with her! So of course I said yes, and then

when she told me who it was, well it seemed rather churlish to refuse and ...’

‘Connie,’ said Sir William hastily interrupting his wife’s flow, ‘I’m

sure there’s really nothing to worry about. Lavinia said in her letter that

this Rose Simpson friend of hers is very nice and perfectly respectable.

Actually, I think it will make quite a nice change from our usual sort of

guest; I was getting a bit bored of them to tell you the truth.’

‘William! You know what Lavinia’s like. She’s never been a very good

judge of character, she just sees in people what she wants to see. Do you

remember that awful girl that she brought down with her a couple of years ago, you

know, that one whose face was covered in freckles and ate with her mouth open!

And this one’s bound to be worse. She’s probably a common little thing covered

in make-up, thinking she looks like one of those American screen goddesses. I

bet she’s got an awful cockney accent too and she won’t know how to behave with

the servants, she’ll probably upset them dreadfully and then they’ll all give

in their notice and walk out and then where will we be? And,’ carried on Lady

Withers quickly, seeing that her husband was about to protest, ‘can you imagine

what Marjorie will say when she hears about it, as she’s sure to?’

Marjorie was the Countess of Belvedere, Lady Withers’ older sister and

Lavinia’s mother. ‘She’s never forgiven me for Lavinia working in that blasted

shop. She blames me, as if it had been all my idea. Just because it was here at

Ashgrove that Lavinia and Cedric made that silly bet that she couldn’t earn her

own living for six months, and Cedric only did it because Lavinia said that she

was sure he didn’t do any work at Oxford, just flounced around pretending to be

intellectual and copying everyone else’s essays. They really can behave like a

couple of children sometimes, the way they wind each other up. I tried to

explain it to Marjorie, that I hadn’t even known that they had made a bet until

she told me about it, but she was not impressed and I could tell she didn’t

believe me; you know how she can be sometimes.’

‘I do,’ conceded Sir William. Much as he loved his wife, he often found

her endless rambling conversation infuriating, but then he had only to remind

himself how much worse things would have been if he had married her sister.

Poor Henry. He didn’t know how the Earl of Belvedere stuck it, but he would

never admit as much to his wife.

‘“Ladies from our class do not work in dress shops, Constance.” That’s

what she said to me as if I didn’t know it already. Apparently even Mrs Booth,

who in Marjorie’s opinion is totally middle class even if the lady in question

considers herself to be from the top drawer, said to her that it would be

totally unthinkable for anyone in

her

circle to serve in a shop, even in

the smartest couture house in Paris, which of course Madame Renard’s certainly

is not, as it’s in a little London back street and sells ready-to-wear dresses,

not even bespoke. Really, William, Marjorie can be so cruel sometimes. She said

that it was all my fault, that they would never have made that silly bet if

they hadn’t been here at Ashgrove. So can you imagine what she’ll say if she

finds out about this Rose girl? She’ll say that I’m condoning Lavinia’s bad

behaviour, no, worse, she’ll say that I’m encouraging it.’

‘There, there, Constance, my dear, you’re worrying far too much.’ Sir

William patted her affectionately on the arm. ‘Stafford will make sure that

everything goes alright.’

‘Yes, dear Stafford, I don’t know what we’d do without him. But that’s

not all, William, if only it was. Cedric’s coming down this weekend as well. He

wired to know if we could have him and you know what boys his age are like. He

didn’t wire until it was too late and he’d already set off, so I couldn’t wire

back and say “No”.’

‘Why on earth would you want to say no, Constance, it will be nice to see

Cedric again, and it will be nice for Lavinia to see her brother. Let’s just

keep our fingers crossed though that they don’t make any more bets while

they’re here.’

‘Well, I expect that’s why he’s coming down this weekend. Not to see

Lavinia or to make any more bets, but to see what this shop girl of hers is

like. Oh ...’ Lady Withers broke off what she was about to say as a sudden

thought flashed across her mind and absentmindedly she clutched onto Sir

William’s arm, digging her nails into his flesh until he winced. ‘Oh, William,

I’ve just had an awful thought. What if this girl decides to set her cap at

Cedric! He can be such a silly boy, so very young and impressionable, just the

sort to fall into her trap. He’s probably never come across a scheming little

minx before. Whatever will Marjorie say if they elope to Gretna Green while

they’re here? It will be such a scandal, Marjorie will never speak to me again

what with Cedric being heir to the title and the estate and …’ Lady Withers

looked up and caught the pained expression on Sir William’s face. ‘I know,

dear, that you think I’m over reacting and being a dreadful snob, but really,

I’m not. You see the

real

reason that I’m so worried about Cedric coming

down this weekend is that Edith’s coming down as well. We arranged it weeks

ago, so you see I can’t really do anything about it without offending her; you

know how sensitive Edith can be, William. I do so hope there won’t be any well

unpleasantness

,

this time. You do remember what happened last time, don’t you, when they

both happened to come down at the same time; of course it couldn’t possibly

have been foreseen, not by anyone, but it was still very unfortunate.’

‘Yes, yes, I do.’ For the first time during their conversation, Sir

William sounded concerned. ‘It’s likely to be damned awkward my dear, but if

there’s nothing we can do about it we’ll just have to manage it the best we

can. Make sure that they sit at opposite ends of the table and all that, and

that they see as little of each other as possible while they’re here.’

‘Yes, you’re quite right. I suppose we’d better explain the situation to

Stafford, although I’m sure he’ll already have everything in hand. You know how

awful I am, darling, trying to work out whom to place next to whom at dinner. I

do hate those awful uncomfortable silences which one is obliged to fill by

saying the most silly, trivial things. Nowadays I just tend to leave it to

Stafford to put out the placement cards at dinner parties because he never gets

it wrong.’

‘Indeed, Sir William, m’lady.’ Neither Sir William nor Lady Withers

had heard their butler enter the room. At times Sir William wondered whether

Stafford actually walked like other people, because he seemed always to glide

noiselessly from one room to another.

‘Oh, Stafford, I knew you would’, said Lady Withers, sounding relieved.

‘Although I do wish you wouldn’t creep up on us so, it’s most disconcerting.

But I should have known that you’d have everything under control.’ She

clapped her hands. ‘Oh, I feel so much better about things already,

everything’s going to be all right, nothing will go wrong, nothing to worry

about …’ And she drifted out of the room in very much the same manner as she

had floated in, humming a tune softly to herself, blissfully unaware that her

original misgivings were to prove quite founded.

‘Oh, Mr Stafford’, said Mrs Palmer, the Withers’ cook-housekeeper, as she

relaxed with her after dinner coffee that evening in the ‘Pugs’ Parlour’, a

sitting-room-cum-dining- room used by the upper servants, ‘I fear we have quite

a weekend in front of us. I suppose everything’s been done as much as can be,

to avoid disasters?’

‘Indeed, Mrs Palmer, it has.’ Mr Stafford’s voice, as always, so Mrs

Palmer thought, was wonderfully calm and reassuring, indeed she was sure that

she had never seen him look ruffled or flustered. ‘Spencer has been instructed

to unpack Miss Simpson’s suitcase as soon as she and Lady Lavinia arrive, and

then Spencer and Miss Crimms will cast their eyes over her dresses and check

that they’re all suitable, especially the dress that Miss Simpson is proposing

to wear for dinner.’

Miss Crimms, Lady Withers’ lady’s maid, who was also sitting in the

parlour, nodded in agreement between sips of her coffee, careful not to spill

any in front of Stafford.

‘And what if they’re not?’ Mrs Palmer asked, intrigued. ‘What then?’

‘We have contingency plans in place, Mrs Palmer,’ replied Stafford

solemnly. ‘Miss Crimms has already looked out some old gowns of her ladyship’s

that we can give Miss Simpson to wear if necessary, gowns that her ladyship is

very unlikely to remember that she ever owned.’

‘Yes, we don’t want her ladyship to turn around and accuse Miss Simpson

of stealing one of her dresses from out of her wardrobes, now do we!’ Miss

Crimms said, unable to suppress a giggle.

‘No, indeed not, Miss Crimms,’ Stafford glared at her, ‘that would never

do. Her ladyship is not to be distressed or inconvenienced in any way, not if

it is within my power to prevent it. As I was saying,’

before I was so

rudely interrupted

, he would have liked to have added, but didn’t, although

the look that he gave Miss Crimms said exactly that, ‘if necessary a suitable

gown will be given to Miss Simpson to wear in place of her outfit, and then it

will merely be a case of persuading her to wear her ladyship’s gown instead of

her own.’

‘And how will you do that, pray?’ asked Mrs Palmer, enjoying the lady’s

maid’s obvious discomfort at being admonished by the butler.

‘We have our ways,’ replied Miss Crimms, wishing to redeem herself as

quickly as possible. ‘Gentle persuasion in the first instance if Miss Simpson

appears amenable, and then if not more rigorous measures can be adopted if

necessary, such as accidently spilling a vase of water or pot of rouge over her

dress when she is about to go down to dinner or, if the dress is too awful,

offering to press it and then scorching it with an iron!’

‘No!’ Mrs Palmer looked appalled. She was quite sure Lady Withers would

not approve of such drastic measures.

‘I only ever did that once, Mrs Palmer,’ confided Miss Crimms, leaning

forward, ‘When I was lady’s maid to a very young lady who shall not be named,

but who was going to go to a ball in a

very

unsuitable dress, that would

have brought much distress to her mother and shame on the whole family if she

had ever gone out in such a thing. But there was no reasoning with her, I can

tell you, for she was a headstrong young madam if ever there was one, stubborn

as a mule. So I said to myself, there’s only one thing to be done, my girl,

you’ll have to ruin that dress so it can’t be worn. So I told her that I’d just

go and press it, and then I scorched it good and proper with the iron, right

down the front!’

‘You never did!’ exclaimed Mrs Palmer. ‘And how did the young lady take

it, did she guess that you had done it deliberately?’

‘Of course she did! And she was that angry that she went as if to slap me

across the face! But I said, “If you do that m’lady, I’ll take this dress

here and show it to your Mama and say as how you were intending to wear it out

and I was only trying to stop you making a right spectacle of yourself, that I

had tried everything else, but that you’d just not listened to me.” Well, that

soon took the wind out of her sails, I can tell you, became as meek as a lamb,

she did. Scared of losing her allowance from her parents, I’ve no doubt!’

‘Yes, well, Miss Crimms,’ said Stafford, gravely, ‘hopefully we will not

have to resort to such drastic measures in this case!’