100 Cats Who Changed Civilization (5 page)

Situated atop London’s Highgate Hill stands a statue of a feline known simply as Dick Whittington’s cat. According to legend, he belonged to a man named Richard Whittington, who lived from 1350 to 1423 and served as mayor of London four times. Yet it is doubtful he would be remembered at all were it not for the stories about his wonderful pet—a pet who, in real life, he probably never possessed.

A great deal is known about the real Dick Whittington. He was the younger son of Sir William Whittington, Lord of the Manor of Pauntley in Gloucestershire. He made a fortune selling fine cloth and was on good terms with both King Richard II and his successor, King Henry IV. He married a woman named Alice Fitzwarren and, of course, served as London’s mayor. After his death, he willed his vast fortune to charity.

And then something strange happened—something that would transform the real Whittington into the hero of a childhood fable. The people of London, anxious to know more about their benefactor,

invented a biography that centered around, of all things, a cat. The centuries-old account casts Whittington as a poor country lad who came to the big city to make a name for himself. He worked for a merchant named Fitzwarren and fell in love with Alice, his daughter. His sole possession was a cat, whom he gave to a sea captain to sell during his voyage.

Sometime afterward, Whittington decided to return to his hometown of Gloucestershire. But as he trudged past Highgate Hill he heard the city’s bells tolling. They seemed to say, “Turn again, Whittington, three times Lord Mayor of London.” So he went back to Fitzwarren’s house, where he learned that the captain he’d given his cat to had returned with incredible news. A foreign potentate whose palace was overrun by rats had bought the cat, paying with a huge pile of gold. Dick instantly became wealthy, married Alice, and eventually became Lord Mayor of London three times as predicted, plus an additional term.

The tale became (and remains) a popular children’s story retold regularly in books, plays, and pantomimes. One doubts that the real Whittington would mind. The cat with whom he shares the limelight has won him lasting fame.

THE CATERER

THE CAT WHO USED PIGEONS

TO HELP A JAILBIRD

Throughout most of human history, politics was a winner-take-all proposition in which losers forfeited their fortunes and lives. Such was almost the case for Sir Henry Wyatt, who was born in Yorkshire, England, in 1460. During the two-year reign of King Richard III, he supported the claims of Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, to the throne. The king had Wyatt imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was kept in freezing conditions, tortured, and fed a starvation diet.

But one day a feline walked through the grate covering the cell’s window and made the acquaintance of the room’s emaciated inmate. Wyatt, overjoyed to have company, petted and praised the cat. The two became fast friends, and the stray promptly set about saving its human companion’s life by killing pigeons and fetching them to Wyatt’s cell.

The famished prisoner gladly accepted them, and he convinced one of his jailers to dress and cook the birds. Soon the feline was referred to as Wyatt’s

acater

(caterer). Thus fortified, Wyatt held out against all adversity until, finally, Richard III was ousted from the throne by Henry Tudor, who was crowned Henry VII. Needless to

say, the former prisoner’s prospects rapidly improved. He was freed from the Tower, given wealth and title, and lived to the ripe old age of eighty.

Through it all he never forgot the kindness of the Tower cat, whose fate is unrecorded. One hopes that Wyatt found a way to help his benefactor, as he did almost every other cat he encountered. “Sir Henry in his prosperity would ever make much of a cat, and perhaps you will never find a picture of him anywhere, but with a cat beside him,” said one historical account.

Today, the Church of St Mary the Virgin and All Saints in Maidstone features a stone memorial to Wyatt, “who was imprisoned and tortured in the Tower, in the reign of King Richard the third, kept in the dungeon, where fed and preserved by a cat.” The monument is a touchstone of sorts for the extended Wyatt family, which thrives in both the United States and Canada—and would be all but extinct were it not for one resourceful feline.

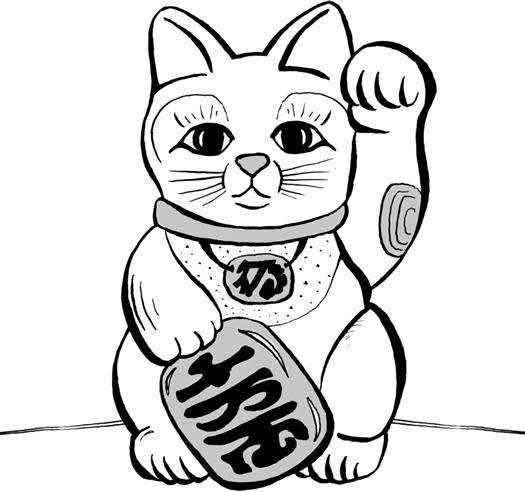

MANEKI NEKO

THE FORLORN TEMPLE CAT

WHO BECAME JAPAN’S SYMBOL

OF GOOD FORTUNE

A visitor to almost any Japanese shop, restaurant, or bar will likely find, crouched near the entrance, a small porcelain statue of a cat. The cartoon-like creature may sport a slight smile and hold a gold coin cupped in one paw. The other paw (either the right or left) will be raised in a beckoning gesture. This is the famous Maneki Neko, or beckoning cat, a charm that supposedly attracts wealth and good fortune to anyone who displays it. But this creature may not be entirely mythological. According to Japanese legend, it is based on a real tortoiseshell tabby—a tabby whose timely invitation to a passing nobleman elevated a humble Buddhist shrine to wealth and fame.

Several different stories purport to tell what happened, but the following is the most commonly recounted: Sometime during Japan’s Edo period (1603–1867), a nobleman rode past a rundown temple outside Tokyo. While passing, he happened to notice the temple master’s cat, which seemed to beckon to him. Intrigued and perhaps slightly unnerved, he dismounted and approached. At that moment a lightning bolt struck the spot on the road he’d just left.

The noble, who believed the humble feline kept him from destruction, endowed his temple home with lands and money. Years later, when the cat who saved his life died, he had the first Maneki Neko figurine created in his honor. According to some versions of the tale, the place in question was the famous Gotoku-ji shrine near Tokyo. Whether this story is true is anyone’s guess. However, the popularity of cat statues among the Japanese is indisputable. They have been produced by the millions, in versions ranging from

piggy banks to dashboard ornaments—all of them designed to attract money and luck to their owners, just as the original feline did.

The wings of pop culture have spread the talisman’s influence around the world—sometimes in unexpected ways. One of the most famous Pokémon characters, Meowth, is an anime incarnation of Maneki Neko. And the ubiquitous Hello Kitty bears more than a passing resemblance to the famous feline. Even her name is considered by some to be a loose translation of that of the beckoning cat.

RUTTERKIN

THE CAT WHO WAS ACCUSED

OF MURDER

During the Middle Ages, European cats received some of the worst press in the history of the species. They were accused of being agents of evil and of serving as familiars for witches. Popes occasionally railed against them, and public disapproval of felines could grow so heated that they would be exterminated from entire towns.

One example of this overreaction took place in Lincoln, England, in 1618. Joan Flower and her daughters, Margaret and Philippa Flower, were accused by the local magistrates of using the dark arts to take revenge on their employers, the Earl and Countess of Rutland. History doesn’t record the reasons for their ire. However, it describes their alleged methods in forensic detail. According to testimony from the women (extracted, as was usual at that time, under torture and intense interrogation), Joan Flower possessed a spirit familiar called Rutterkin, which manifested itself in the form of a sinister-looking black cat. The feline was their weapon of choice when casting spells. One favorite tactic was to steal gloves from members of the Earl’s family, boil them, prick them full of holes, and then rub them along Rutterkin’s back. According to court proceedings, this

odd-sounding bewitchment accomplished the death of the Earl of Rutland’s son, Lord Ross.

And what did the supposedly demonic cat get in exchange? In addition to the women’s immortal souls, he also was allowed to feed on Joan Flower’s blood.

The death of Lord Ross, plus various odd illnesses suffered by other close relations, finally drove the Earl of Rutland’s family to believe that the Flowers were hatching some sort of plot against them. The women, after enduring all the usual inducements available to the medieval legal system, signed confessions. Joan died in custody, but her daughters were burned at the stake.

What became of Rutterkin? One hopes he had the good sense to simply slink away. His kind were maligned throughout Christendom, making it impossible for the hapless feline to get a fair hearing. Even today, in our supposedly enlightened era, his descendants are slandered in everything from Halloween cards to cheap, straight-to-video horror flicks. In a very real sense, today’s black cats have one paw in the Dark Ages.

SINH

THE LEGENDARY CAT WHO

WAS THE FIRST BIRMAN