100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (9 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

18. Dodger Stadium

In the center is a pitcher's mound, enclosed by four bases forming the corners of a diamond, 90 feet apart. That's standard. Everything else that surrounds it is a matter of choice.

At Dodger Stadium, the diamond is surrounded on two sides by a symmetrical outfield, laden with the most pristine grass in Southern California. Since 1962, this has never been anything less than perfect. It hasn't been limited to baseball players; it has been the earth under Beatles, Globetrotters, Olympians, Tenors, and a Pope.

At the rim of the outfield is a fence, eight feet high from the left field bullpen to the right, waist-high as you near the foul poles. The wall has changed with the times, alternating different shades of blue; in later years adorned with homages to Dodgers history; still later with welcome-back-to-the-real-world advertising. In the 21

st

century, scoreboards were embedded in its face. The walls have not always been forgiving; for decades they went without sufficient padding, contributing to a key shoulder injury to Darryl Strawberry in the 1990s. James Loney lasted one experimental inning in the outfield in 2007 before his knee fought a losing battle with the joint between the scoreboard and the fence.

Beyond the wallsâcloser to home plate today than they were when the stadium openedâare the pavilions, which can be the Sahara on a day game but a grand ol' time otherwise. Famously, in the initial decade, Willie Stargell became the first player to hit a ball over the pavilion roofsâand the second as well. For nearly two decades, no one else duplicated the feat until Mike Piazza and Mark McGwire in the '90s, homering over the roof-level ring of retired Dodger numbers.

Above the pavilion are two scoreboards at left and right. Despite a remodel, the latter at its heart hasn't changed, offering the lineups and score-by-innings. Its partner used to be made of similar stuff, offering messages and spelling out graphics in text boxes, like a giant number 19 to mourn Junior Gilliam, who was stolen from the team and this world too soon. Then, in time for the 1980 All-Star Game, the left-field scoreboard led ballparks into the video age with DiamondVision and forever changed the experience of attending a game.

Â

Â

Â

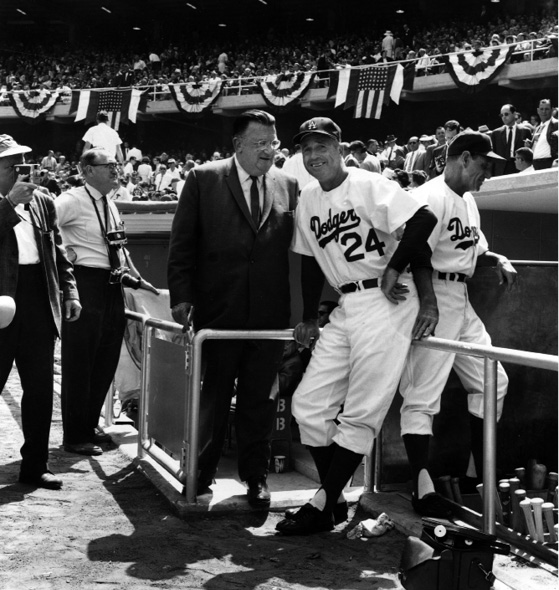

April 10, 1962, was Opening Day at Dodger Stadium, and no one was prouder of the $23 million stadium than visionary Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley (center). Next to him was the popular Dodgers manager Walter Alston (No. 24) and farther right is Dodgers coach Leo Durocher. All three are now members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Photo courtesy of www.walteromalley.com. All rights reserved.

Center field offers no seating, just a black batter's eye and a spot for the TV camera, like the one that got thudded by Jose Canseco's World Series Game 1 grand slam that should have spelled the end of the '88 Dodgers, the camera through which most baseball fans in their bars and living rooms see every pitch. The center-field walls open for new-model cars to drive through on Fan Appreciation Day and for ambulances to come to the aid of the stricken, like Alex Cora, Kazuhisa Ishii, or umpire Kerwin Danley.

Out beyond center field lies the mammoth parking where Dodgers fans safely in their seats can gloat at those struggling to arrive. As stolid a fixture as any in Dodger Stadium's first 46 years, even this became positioned for change with the 2008 announcement that the McCourt-owned Dodgers would breed shops and restaurantsâalong with the nirvana of a Dodger historical museumâover the pavement. But those plans were shelved with the global recession and local depression of the McCourts' ugly denouement. Whatever alterations might come someday, one only hopes that the view beyond the parking never changes: the hills of Elysian Park that for so long displayed “THINK BLUE” in bold letters resting atop, and further back, the San Gabriel Mountains offering as resplendent a backdrop as any in baseball.

Circle around the perimeter, and you come to the rear of the stadium, offering a reminder to those who might otherwise have no idea that, yes, Los Angeles does have a downtown, and you can spy on it from here and even fantasize about a tram or

Simpsons

-esque escalator that would link the stadium to the city's public transportation nexus. But back to reality. Turn around with your ticket, and find your seat: in the Top Deck with its vertigo-inducing but rewarding view; or in the Reserved Level that is the most populated part of the stadium; or among the affluent on the Club Level (which evolved from exclusivity to downright largesse when suites were added between the Stadium Club in right field and the Dodger executive offices in left); or down to the Loge Level where the seats are upper class if not Hearstian; or down to the Field Level that just seems to expand, expand, expand, encroaching into and populating what used to be roomy foul territory. The home and visitor dugouts have expanded as well. It's all about real estate in Southern California, after all, and you've got to keep up with the Joneses.

It's a short walk from the on-deck circle to home plate, back to that central, fixed diamond of Dodger Stadium. Who knows how often a batter steps out of the batter's box and takes a look around and realizes what the people in the stands realize: that much of the wonder of Dodger Stadium remains, even on your 100

th

or 1,000

th

visit. For all the changes, for however loud or lewd it has gotten in some ways, it is still a

ballpark

. It is a tremendous place to watch a baseball game.

Â

Â

Our Little Secret

They're not foolproof, but here are three good bets for cutting through the traffic to Dodger Stadium.

1) From the southbound Harbor/Pasadena (110) Freeway:

⢠Take the Academy Road exit.

⢠Follow Academy Road to Solano Canyon Drive and turn left.

⢠Proceed ahead to Dodger Stadium entrance.

2) From the northbound Harbor/Pasadena (110) Freeway:

⢠Take the Academy Road exit.

⢠Turn right on Solano Avenue.

⢠Turn right on Amador Street.

⢠Turn right on Jarvis Street.

⢠Turn left back onto Solano Avenue.

⢠Turn left onto Solano Canyon Drive.

⢠Proceed ahead to Dodger Stadium entrance.

3) From the intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Beaudry Avenue:

⢠Head northeast on Beaudry to Alpine Street and turn right.

⢠Turn left on Figueroa Terrace.

⢠Continue on Figueroa Terrace, bearing left.

⢠Turn right on College Street.

⢠Turn left on Chavez Ravine Place.

⢠Bear right onto Stadium Way.

⢠Continue toward Dodger Stadium entrance, which will be on your left.

19. Don't Turn Your Back on a Hero Who's Down on His Luck

After Fernandomania, there was Nomonia (or, as the less eloquent called it, Nomomania). Allowing one hit in five shutout innings in his first major league game, allowing two hits in seven shutout innings while striking out 14 in his fourth, Hideo Nomo whipped the Dodger faithful into a frenzy. It wasn't the rags-to-riches, babe-in-the-woods mind-spinner that Valenzuela caused, but it was a phenomenon nonetheless.

Other than one game started by Giants reliever Masanori Murakami in 1965, no Japan native had ever been a starting pitcher in the NL or AL. And here was the 26-year-old Nomo, the first Japan League player to come to America in his prime, posting 16 strikeouts June 14, then back-to-back games of 13 later that monthâ11 double-digit strikeout games in 28 starts overall during his rookie season. His average of 11.1 strikeouts per nine innings was the fifth-highest single-season total in major league history at the time. He emerged as the ace of the '95 Dodgers (2.54 ERA/150 ERA+), not to mention the NL Rookie of the Year. With two days remaining in the regular season and the Dodgers leading the Colorado Rockies by one game in the NL West, Nomo struck out 11 while allowing one earned run in eight innings, enabling the Dodgers to clinch a tie. One game is the margin by which the Dodgers won the division, and they almost certainly wouldn't have done so without him.

In 1996, Nomo remained strong, even climbing the Mt. Everest of pitching feats by throwing a no-hitter at the hitting capital of baseball, Colorado's Coors Field. Chris Jaffe, writing for

The Hardball Times

, called it the second-most impressive no-hitter in baseball history. But like so many other pitchers, Nomo would battle arm issuesâviolently high pitch counts were a featured element of his Japan-era backstoryâand his performance declined in subsequent years for the Dodgers. After starting the 1998 season with a 5.05 ERA (80 ERA+) in 67

2/3

innings, Los Angeles shipped him with Brad Clontz to New York in a trade for journeymen Dave Mlicki and Greg McMichael. Thus began the peripatetic phase of his career. The Mets, Cubs, Brewers, and Tigers would all release him over the next 30 months, and the Red Sox let him leave as a free agent even though he pitched his second career no-hitter in his first start of the 2001 season.

Nomo found his way back to Los Angeles, and just like that, Nomonia started spreading all over town again. He had a 3.39 ERA (112 ERA+) and 193 strikeouts in 220

1/3

innings in 2002, and then in 2003, he helped anchor one of the great Dodgers pitching staffs of all time with a 3.09 ERA (130 ERA+) and 177 strikeouts in 218

1/3

innings.

And then, in 2004, it all vanished. Stunned by a six-run fifth inning in his first start of the season, Nomo never got his ERA below 6.00. He struck out more than three batters in only four of 18 starts. As far as being a competent pitcher, Nomo was done. Yet Dodgers manager Jim Tracy kept sending him out to the mound every fifth game. Dodger Stadium fansânot all of them, but enough to make an impactâstarted booing him.

Booing, in its many forms, is part of baseball. Some fans are raised in it, some can't help it. Some feel it's harmless venting; some intend it as anything but. Few would call it a particularly mature act, but who ever said you had to be mature at a baseball game?

At some point, however, there has to be a line. There has to be a barrier you don't cross, even if you're unhappy that you've shelled out big bucks to see what's turning into a big loss. And if nowhere else, that barrier has to come with the kind of player that has won huge games for you, thrilled you, that has given his all for you, that has been nothing but professional for you. And if he's gotten well-paid for the work, well, ask yourself if you'd turn down the money.

If you're a Dodgers fan, or any kind of sports fan, remember Hideo Nomo. Remember context. When someone's been a hero for you, cut him some slack during the rough times. Then, more than ever, is the time to cheer him.

Â

Â

Â

20. Dodger Dogs

Dodger Dogs are controversial, and not for Upton Sinclair

The Jungle

reasons.

The fact is, Dodger Dogs are not a single, static entity. Dodger Dogs, like the Dodgers, are different from moment to moment.

First, the Dodgers sell more than one type of hot dog. The nominal Dodger Dog is a footlong tube that out-stretches the bun, but some prefer the shorter, squatter, and arguably tastier all-beef dog.

Depending on where in the ballpark you purchase them, Dodger Dogs are sometimes grilled, sometimes boiled. And if you end up at a boiled stand, you might as well not even bother. Not that it's bad, but it doesn't have the snap that you'd like from a hot dog. Essentially, a Dodger Dog isn't a Dodger Dog without the taste of char. It's part of the food's character, and it's frankly a little silly that the Dodgers sometimes ignore this. And then, even on the grill, Dodger Dogs can be undercooked or overcookedâthere's no doubt that the dog is a precision instrument.

Condiments are also an issue. The Dodgers have been better in recent years at providing spicy mustard in addition to yellow, but the relish can sometimes err on the runny side. Ketchup seems to go well on a Dodger Dog, though of course there are some regions in this country that would consider a ketchup-laden dog a sin against nature.

All of this might seem to make the Dodger Dog an impossible dream, something mythological rather than achievable, and to be sure, some longtime fans have given up on the pursuit and warned other visitors and first-timers off the chase.

But you can get an ideal Dodger Dog. And when you do get one and take it to your seat at the ballpark, it can seem as perfect as the Dodger Stadium grass and the white uniform with blue lettering, as perfect anything you've ever tasted.

It's worth it to endure the subpar Dodger dogs for the champion dogs. I mean, this is baseball, right? If they were all great, that'd be nice, but just a little too easy, wouldn't it?

Â

Â

Face the Music

Maybe Dodgers fans don't think much about the organ player the first time they go to the ballpark. Maybe they took Gladys Goodding for granted at Ebbets Field, or paid no mind to Bob Mitchell, Don Beamsley, teenager Donna Parker, Helen Dell, or Nancy Bea Hefley while absorbing the Dodger Stadium experience.

But when it comes to memories, that's when the organ player is important. You can hear rock music anywhere. The organist gives Dodger Stadium its own personality. It's swimming against the 21

st

-century tide, but the organist needs to be celebrated, not diminished.