1066 (15 page)

Authors: Andrew Bridgeford

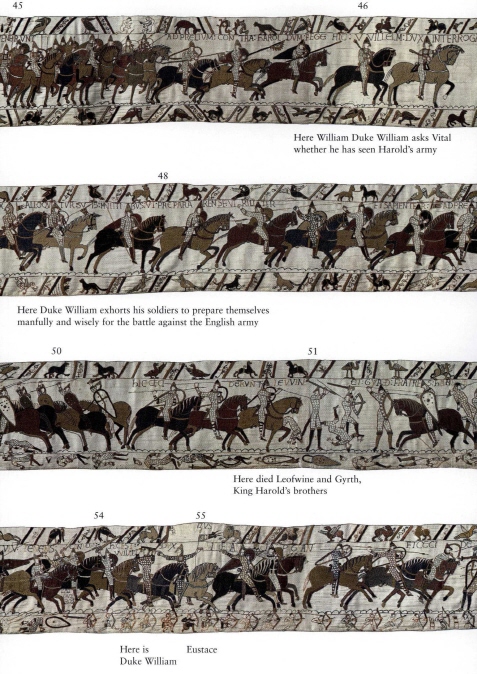

It is the picture, not the words, that shows where his sympathies lie, for the word FRANCI is pictorially linked, inextricably, to the preceding image of Count II Eustace of Boulognes [scene 55]. A great lion in the upper border marks out the letters F and N with its paws whilst Eustace's enormous banner shares the same, uniquely elongated compartment in the border and even touches the lion's chest. What is more, the knight who takes up the charge carries a lance which underlines the very word FRANCI and at the same time he is pointing back at Count Eustace with his index finger. To make the connection even more explicit, the far end of the lance is touched by Eustace's left hand; it even seems to grow out of his skin. There can surely be no doubt, at this deeper level, that it is the French under Count Eustace, and not the Normans, who are indicated by the word FRANCI. Extraordinary as it may seem, all those charging knights in the Bayeux Tapestry, so often described as 'Normans', are at the deeper level nothing of the sort. This is a whole new layer of meaning, a layer of meaning which has lain hidden and unsuspected for almost a thousand years. The implications are profound. The tapestry began by undermining the Norman claim by subtly recording the English viewpoint and now it has discreetly highlighted the controversial Count Eustace II of Boulogne and his northern Frenchmen over and above the Normans. So much for telling the story 'strictly from the Norman point of view'.

Roused by the trio of Odo, William and Eustace, the bloody fighting resumes in earnest and the battle is now entering its final bitter stage. Up to now no clear advantage had been gained by either side, and a great many lay dead or maimed. If William could not deliver a killer blow before dusk the situation would probably be dire. Harold's reinforcements would soon arrive, perhaps the next day, perhaps in the days that followed, and the battered ducal army would be no match for fresh troops eager to defend their country and to repel the invaders.

The embroidered knights press on with another attack deep into the redoubtable English position. A French knight seems to be intent on pursuing one housecarl in particular, for he ignores the nearest enemy and thrusts his sword straight at the face of the one standing behind [scene 55]. Another French knight has been knocked out of the saddle but he still manages to ride on the neck of his horse and strikes down a goatee-bearded Englishman with a single blow of his sword. Presumably these two incidents really happened. Next, in a very enigmatic picture, a knight with spurs on his heels is standing on the ground; he is the only knight not on horseback in all the battle scenes. Grabbing the hair of an unarmed Englishman, he is about to decapitate him in a formal-style execution [scene

56].

His victim's decapitated body lies beneath, in the lower border, together with the sword that did the job. As he performs this gruesome task, the knight has another sword in his belt. The handle of his belted sword protrudes from his groin as if it were a penis, whilst its tip seems about to obscenely penetrate a stallion behind. The meaning of this scene remains obscure.

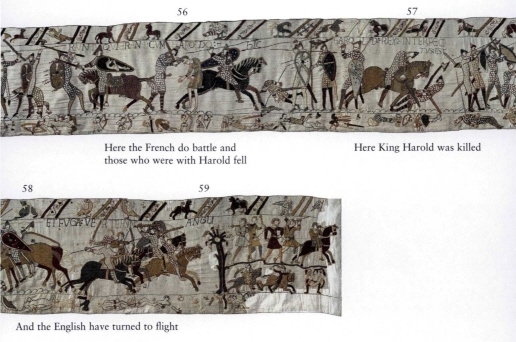

The lower border is now full of archers, shooting skyward in a desperate attempt to inflict further damage on the English position. Harold is standing amidst his men by the dragon banner of Wessex. He is still holding fast; but the end is near. Under the inscription HIC HAROLD REX INTERFECTUS EST (Here King Harold was killed) the King of the English appears to have been suddenly hit in or around the eye by an arrow [scene 57; plate 12]. He must be in agony now, as he tries to extract the shaft from his face, but then a mounted knight arrives at the scene and swinging down his heavy sword he strikes Harold on the thigh. The king collapses. A great English battleaxe, presumably representing Harold's military power, splits in two under his falling weight. The sprightly Harold Godwinson, whose tragic story has been animated so poignantly and memorably in the Bayeux Tapestry, now lies dead upon the very ground that he was attempting to defend.

The tapestry's image of Harold stuck by an arrow in the eye is one the most famous and enduring in English history;but it is not universally accepted as the correct reading. It has sometimes been argued that Harold is not, in fact, the famous figure wrenching an arrow from his face under the word HAROLD but rather that he is only the second figure, the one struck on the thigh beneath INTERFECTUS EST (was killed).

10

This has never been entirely persuasive.

11

It rests upon some doubtful generalisations about the conventions followed by the artist and ignores the obvious implication that the arrow-in-the-eye figure who stands under (and even breaks up) the letters HARO/L/D must be the eponymous casualty. He even looks up at the letter O in his name. Moreover, the tapestry is not alone in telling the arrow-in-the-eye story, or something like it. The arrow story may have been circulating in some Norman accounts even before 1080

12

and in the first third of the twelfth century two Anglo-Norman writers recorded a version of Harold's death that seems very close to the tapestry. The first, William of Malmesbury (c. 1125), wrote that Harold's 'brain' was 'pierced by an arrow' before 'one of the knights hacked his thigh with a sword as he lay on the ground'.

13

The second, Henry of Huntingdon (c. 1130), was the earliest known English writer explicitly to mention Harold's eye: 'the whole shower sent by the archers fell around King Harold and he himself sank to the ground, struck in the eye', whereupon 'a host of knights broke through and killed the wounded king'.

14

Whether these writers were basing their accounts on an interpretation of the Bayeux Tapestry or were recording a similar but independent tradition, the view that the Tapestry is following the arrow story is rendered more probable. Moreover, in his poetic re-rendering of the work as a luxurious wall hanging around Countess Adela's bedchamber, written between 1099 and 1102, Baudri of Bourgeuil writes that Harold was hit by an arrow, albeit without specifying the point of impact: 'a shaft pierces Harold with deadly doom'.

15

This was evidently Baudri's interpretation of the tapestry and as a contemporary observer it may be assumed that he was familiar with the artistic conventions of his day.