1492: The Year Our World Began (16 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

Savonarola denounced astrology, the humanists’ favored means of political forecasting, as “contrary not only to holy scripture but also to natural philosophy.”

Girolamo Savonarola,

Tractato contra li astrologi

(Florence: Bartolommeo di Libri, ca. 1497). Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Library.

In November, Politian hit back with

Lamia.

The title alluded to a classical commonplace—a mythic queen who, thwarted in love, lost her reason and turned into a child-murdering monster. In Renaissance scholars’ learned code, she represented hypocrisy: Politian was accusing Savonarola of abusing learning against learning. At a time when Europe was convulsed by fear of witches, he likened his adversary to hags who

reputedly plucked out their eyes at night in a diabolic ritual, or to old men who remove their spectacles along with their false teeth and become blind to self-criticism. Philosophy, Politian insisted, is the contemplation of truth and beauty. God is the source of our soul and our mind. He gives them to us for the scrutiny of nature, which in turn discloses God.

Savonarola also differed bitterly from Lorenzo’s circle on the subject of poetry. Lorenzo and his followers loved it and practiced it. Savonarola claimed to see it as an abomination. On February 26, 1492, Politian published an outline of knowledge, which he called the

Panepistemon

—the Book of Everything. He made what at first glance seem extraordinary claims for his own favorite art of poetry. The poet’s was a special kind of knowledge, which owed nothing to reason or experience or learning or authority. It was a form of revelation, divinely inspired. It was almost the equal of theology—a means of revealing God to man. Politian was speaking for most of his fellow scholars. He was uttering a commonplace among Florence’s academicians. Shortly afterward, in the summer of the same year, after the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Savonarola’s reply appeared in print. The idea that poets could write in praise of God was sickeningly presumptuous. “They blaspheme,” he declared, “with vile and stinking lips. For not knowing Scripture and the virtue of God, under the name of the most loathsome and lustful Jove and other false gods and unchaste goddesses and nymphs, they censure our omnipotent and ineffable Creator whom it is not at all permitted to name unless he himself allows it in Scripture.” Poetry “wallowed among the lowest forms” of art.

16

Botticelli painted his enigmatic allegory of Calumny to defend the theology of poetry from Savonarola’s imprecations.

17

In sermons, meanwhile, the friar began calling for the books of poets and Platonists to be burned. A couple of years later, when his supporters seized power in Florence and drove out Lorenzo’s heir, they made a bonfire of Medici vanities and outlawed the pagan sensuality of classical taste.

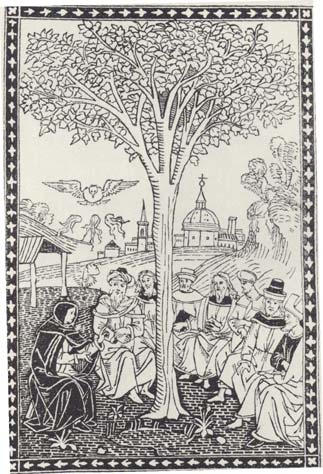

The Florentine engraver of the 1500 edition of Savonarola’s

Truth of Prophecy

imagines him debating the topic with the learned of all religions.

Girolamo Savonarola,

Dialogo della verità prophetica

(Florence: Tubini, Veneziano and Ghirlandi, 1500).

In retrospect, Savonarola came to see Lorenzo’s death as a kind of showdown with the values he hated and a kind of divine validation of his own views. He claimed to have predicted it. The night before lightning struck the cathedral he had another of his fits of sleeplessness. It was the second Sunday of Lent, and the lectionary called for a sermon on the subject of Lazarus, but Savonarola could not concentrate on the text. God seemed to take over. “This saying,” the friar later recalled, “came out of my mind at that time, ‘BEHOLD THE SWORD OF THE LORD, SUDDEN AND SWIFT, COVERING THE EARTH.’ So I preached to you that morning and told you that God’s wrath was stirred up and that the sword was ready and near at hand.”

18

Another death Savonarola claimed to predict occurred on July 25: that of Pope Innocent VIII. To understand the significance of his death, a retrospective of his life is necessary. Innocent never impressed anyone very favorably. The Florentine ambassador, Guidantonio Vespucci, summed up common opinion diplomatically when he said the pope was “better suited to receive advice than give it.”

19

Innocent became pope at a stalemated conclave in 1484, allegedly by signing petitioners’ claims for favors in his cell at night during the voting. He was renowned for affability and good intentions. But—even in his rare intervals of good health—he was hardly equal to the job.

Most of his pontificate was dominated by violent quarrels with the king of Naples, who scorned the papacy’s historic rights to jurisdiction in his kingdom and incited rebellions in the papal states. The throne of Naples, and that of Sicily, which was tied to it, had been disputed between rival claimants from Spain, France, and England for over two hundred years—ever since Spanish conquerors installed the ruling Aragonese dynasty and displaced the French House of Anjou, whose descendants never ceased to assert their claims and who were still plotting coups and launching raids. The Angevin claim was a subject of dispute in its turn between the houses that descended from the line: those of the dukes of Lorraine, who had a strong claim but little power with which to enforce it; the kings of England, who had

long abandoned interest in Sicily; and the kings of France, who—because of their growing power, if for no better reason—were increasingly realistic claimants.

Another of Savonarola’s prophecies was that France would invade Italy in order to seize the Angevin inheritance. France was the sword that pierced his many visions. But you did not need to be a prophet to know that an invasion was only a matter of time. As Innocent’s pontificate unfolded, everyone could see it coming.

Expectations focused on the king of France, Louis XI, who united Angevin claims to Naples and Sicily because he was the residuary legatee of the previous claimant. Louis, however, was too prudent and practical to risk launching long-range wars. Louis was not made for glory. His mind was calculating, his methods cautious, his ambition worldly. “I will not say I ever saw a better king,” wrote his secretary, “for although he oppressed his subjects himself, he would not allow anyone else to do so.” By a mixture of astuteness and good fortune, he had a glorious reign. His great rival, Charles the Bold of Burgundy, fell at the Battle of Nancy, in 1477, in an attempt to re-create the ancient kingdom of Lorraine. The English, who had carved an empire in France by violence early in the century, had been expelled from the mainland by 1453, their former dominions firmly attached to the crown. Louis was free to assert royal power in parts of France that had formerly been merely nominal parts of the kingdom, including Languedoc in the south and Brittany in the north. France was the fastest-expanding realm in Christendom. Success nourished ambitions, excited envy, and attracted the eyes of outsiders in need of allies.

Louis’s son and heir, Charles, had an upbringing that might have been calculated to turn him away from the paths his father followed. Louis was a neglectful father, but when he did take a hand in his son’s education, he was full of uncharacteristically high-minded counsel.

God our creator has given us many great favors, for it has pleased him to make us chief, governor, and prince of the most noteworthy

region and nation on earth, which is the kingdom of France, whereof several of the princes and kings who preceded us were so virtuous and valiant that they gained the name of Very Christian King, by reducing many great lands and divers nations of infidels to the good Catholic faith, extirpating heresies and vices from our realm, and preserving the Holy, apostolic See and the holy Church of God in their rights, liberties, and prerogatives, as well as by doing various other good deeds worthy of perpetual memory and in such a way that a certain number of them were held to be saints living forever in the very glorious company of God in his paradise.

20

This rhetoric was traditional in the French royal house, as was the doctrine that the king was the servant of the people. But like most rhetoric, it tended to get honored more in the breach than in the observance. Charles’s values—his frameworks of understanding his role as a Christian king—were drawn more from stories of knights than of saints, more chivalry than clerisy. He ascended the throne as Charles VIII in 1483 at the age of thirteen, resolved to be as unlike his father as possible. Their personalities were at odds. Where Louis had been worldly, Charles was wooly; whereas the father was a realist, the son was a romantic. He spent most of his childhood in his mother’s company, reading her books. He became immersed in what we would now classify as chick-lit: romantic tales of chivalry, much the same kind of stuff that turned Columbus’s head—the medieval equivalent of dime novels, in which, typically, heroes undertook perilous journeys to conquer distant kingdoms and marry exotic princesses. In the

Histoire de Mélusine

, Charles read of a queen’s sons—young men like himself—who launched adventures of conquest in Cyprus and Ireland.

Lady, if you please, it seems the time has come for us to undertake a journey, so as to learn of foreign lands, kingdoms, and places and win honor and good renown on distant frontiers…. There we shall learn what is different about distant lands and what they have in

common with our own. And then, if fortune or good luck is willing to befriend us, we would dearly like to conquer lands and realms.

21

It would be hard to imagine a program that more exactly foreshadowed Charles’s ambitions. Taking her leave of her adventurous sons, Mélusine grants them leave to do “what you wish for and what you see as being to your profit and honor.” She advises them to follow all the rules of a chivalrous life, adding counsel that seems to anticipate Charles’s methods as a conqueror:

And if God gives you good fortune and you are able to conquer land, govern your own persons and those of your subjects according to each person’s nature and rank. And if any rebel, be sure to humble them and make clear that you are their lords. Never lose hold of any of the rights that belong to your lordship…. Take from your subjects your rents and dues without taxing them further, save in a just cause.

22

In one aspect, however, the successors of Mélusine’s sons failed to follow her advice. “Never,” said the heroine, “tell of yourselves what is not reasonable or true.” Writers of chivalry, by contrast, filled their chronicles with marvels and fables, improbable episodes, fantastic monsters, and impossible deeds. People treated them as true, much as modern TV addicts relate to their soap operas. Scenes from fictional pilgrimages adorned stained-glass windows at Sable and Chartres. Charles VIII was among the many readers chivalric tales suckered.

Even more relevant to Charles’s own prospects was

The Book of the Kings’ Three Sons,

in which young heirs to the thrones of France, England, and Scotland quit their homes secretly to fight for the king of Naples and his beautiful daughter, Yolande, against the Turks. “If you undertake the journey,” urged the knights who sought the princes’ help, “you will learn knowledge of all the world. Everyone will be happy to be your subject. Neither Hector of Troy nor Alexander the Great ever had

the renown you will gain after your death.” In August 1492, when he was planning his own expedition to Naples, he read the book afresh. His moral education was largely based on a book of chivalric examples drawn from stories of the Trojan War and presented in the form of dialogues between Prince Hector and the Goddess of Wisdom.

23

Historians have tried to discard the traditional view that tales of chivalry besotted Charles VIII and filled him with romantic notions. But none of the alternative explanations for his behavior works. There was no economic or political advantage to be gained from invading Italy, whereas the conclusion that storybook self-perceptions jostled in the king’s mind seems inescapable. As heir of René of Anjou, he succeeded to a great romantic lost cause. Beyond Naples and Sicily lay the lure of Jerusalem, the long-lost crusader kingdom. The title of King of Jerusalem, though disputed by other monarchs, went with the Sicilian throne. Charles’s accounts show that he remained an avid collector of chivalric books throughout his life. He identified with a former conqueror of Italy, his namesake Charlemagne, whom many writers reworked as a fictional hero. He called his son Charles-Orland, after Roland, Charlemagne’s companion, who, in fictions his legend spawned, supposedly roamed southern Italy performing deeds of love and valor and who, in an equally false and venerable fiction, died fighting Muslims. Charlemagne was more than a historical figure: legends cast him as a crusader and included a tale of a voyage to Jerusalem, which he never made in reality. He was a once and future king who, in legend, never died but went to sleep, to reawaken when the time was ripe to unify Christendom. The legend blended with prophecies of the rise of a Last World Emperor, who would conquer Jerusalem, defeat the Antichrist, and inaugurate a new age, prefatory to the Second Coming.

Italians with their own agendas encouraged Charles’s fantasies. When he entered Siena, the citizens greeted him with paired effigies of himself and Charlemagne, his supposed predecessor. In the violently divided politics of Florence, some citizens wanted him as an ally against others. Venetians and Milanese wanted him on their side in their wars

against Naples and the pope. When popes had quarrels with Naples, they wanted him to fight on their behalf. When Charles was still a small boy, Sixtus IV had sent him his first sword as a Christmas gift.