(2013) Looks Could Kill (2 page)

“Yes, I’m very sorry, we’ll need to do something about Emma’s behaviour,” George replied.

And so Emma’s first birthday party ended, leaving frayed tempers, upset children and a substantial amount of chocolate cake on the carpet. Mary fretted at the thought of how she would ever restore the carpet to its former pristine condition. Emma was scolded but still didn’t really understand what she’d done wrong.

“What do we do, George? Her behaviour is wearing me down.”

“Well, dear, what about a nursery? She might do better if she spent more time with children her own age.”

And so Emma’s parents found a nice, fairly local Montessori school whose stated aim was to “create a safe, happy and caring environment.”

On the first day, Emma’s parents dropped her off after speaking with the nice Montessori person, who assured them that Emma would be well cared for – and at considerable expense, it should be pointed out. Shortly thereafter, Emma showed her displeasure at being abandoned by her parents by dropping her nappy and glaring at staff that came to rectify the situation. Both staff complained of feeling unwell and had to go home early, resulting in the nursery being closed early that day.

On the second day, Emma’s parents were counselled about her unacceptable behaviour, which the nice Montessori people believed reflected what was happening in the parental home and should be dealt with in situ rather than in an environment where vulnerable infants might suffer. Emma’s mother was called back later in the day to resolve another messy situation after Emma had thrown a tantrum and half-a-dozen infants had vomited their breakfasts in the play area. Emma’s mother was not happy to have to think about it.

Sadly, Emma’s time at the nice Montessori school lasted all of three days, and by the end of that duration, the nursery was considered unsafe and unhappy for infants and staff alike.

So plan A was abandoned and plan B put into place: back home where Emma belonged with her mother and would be safe, happy and thoroughly cared for.

February 1965

Emma was now two years-old and fully meeting her expected developmental milestones. Her speech was particularly impressive. Her television viewing had also moved on, and her favourite programme now was Noggin the Nog. Emma said she really liked the man’s voice, which made her feel sleepy.

One day, when it was just her mother and teddy at home with her, Emma heard strange noises coming from the bathroom. Emma opened the door and saw her mother with something sharp in her hand and something red dripping onto the floor. Emma immediately recognised this as blood.

“Mummy, Mummy!” she cried. ”You’re bleeding!” Emma rushed in to help her.

“No, Emma, it’s nothing,” she said, “Mummy isn’t hurt. You go outside and play with teddy.”

This left Emma feeling very confused. Blood was red and red was bad. She’d seen blood before when she fell down and cried because it hurt. Therefore she was sure her mother must be hurt. It was all very muddling.

So Emma did as her mother said and went out to play with her teddy bear. Teddy was a particularly special teddy bear that Father Christmas had given to Emma last Christmas and she loved him a lot. Her mother and father had also given her a nurse’s outfit for Christmas, but Emma said she wanted to be a doctor like her father. Teddy and Emma used to play doctors and nurses, but Emma was always the doctor.

A few weeks after the bathroom episode, Emma’s mother gave her a little present wrapped up in some pretty paper. She was very excited and opened it. Inside, there was a little knitted jacket that her mother had made for teddy. Emma thanked her mother a lot for it and put it on teddy. But when her mother was gone, Emma took it off teddy and kissed his tummy better. Emma thought there was too much red in the jacket and that the red looked too much like blood. Emma didn’t want teddy to be hurt. Emma and teddy went outside to the bottom of the garden where her father had lit a bonfire. Emma threw the jacket on the bonfire as far as she could. Emma and teddy walked back inside. Emma could see her mother looking from the window watching them. Her mother was crying.

Emma wanted to say sorry to her mother but she wasn’t sure what she had done wrong. Emma thought she was protecting teddy from the red in the jacket and that seemed right to her. Her mother’s present was a gift and that also seemed right to her. But teddy came first. He was the one Emma really loved. And Emma still didn’t understand why her mother was bleeding in the bathroom but didn’t say she was hurt and didn’t want Emma to help her.

As well as playing doctors and nurses, Emma and teddy also enjoyed drawing and painting, although teddy wasn’t very good at it. Emma once drew a picture of her mother, herself and teddy in the house, but her mother cried when she gave it to her. Emma had coloured it in with her box of paints, but she thinks that must have upset her. Perhaps she used too much red.

Emma and teddy had so much to learn about her mother.

August 1966

A middle-aged woman knocked on the door to Mrs Brown’s study.

“Come in,” said Mrs Brown.

Her secretary entered the study carrying a silver tray with an envelope on it.

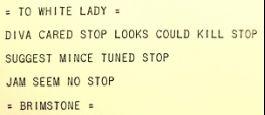

“Ah, thank you, Hermione,” said Mrs Brown. “Now let’s see. What do we have here? How interesting: a telegram.” She opened the envelope and read the contents:

Mrs Brown jotted the letters down on a bit of paper and rearranged them:

VICAR DEAD LOOKS COULD KILL

SUGGEST INDUCEMENT

EMMA JONES

She remembered that incident even though it had been a few years ago and had wondered what to make of it at the time. Brimstone might be on to something, Mrs Brown thought. She would need to keep a look out and do whatever she could do to facilitate proceedings.

“Hermione, I believe we need some more of those brochures printed,” said Mrs Brown. “I think we should offer a generous discount to those in the medical profession. Let’s say 30% off for each term’s fee. And perhaps extend that to those in the dental profession, too.”

“I’ll get on with that right away, Georgina,” said Hermione.

February 1967

Emma had reached the age of four and kindergarten beckoned. Fortunately, there was a perfectly good establishment in her village – in a nice, sprawling, Victorian house to be exact – that was run by Mrs Brown and known, simply, as ‘Mrs Brown’s’. If you were to meet her, you’d understand why the place had a reputation for turning out well-rounded children fit for the next rung of the education ladder: she was matriarchal but matronly; friendly but firm; and she smelt of wholesome things like apple and cinnamon. All this apart from the apples and cinnamon was well explained in the glossy brochure that Emma’s parents had mulled over towards the end of last year. Emma’s mother was particularly pleased to see that Mrs Brown’s offered a substantial discount to members of the medical profession.

And so the day came for Emma to start at Mrs Brown’s.

Now Emma was quite a pleasant-looking girl and total strangers would stop and bend down to say things like: “What a pretty little thing she is”, “What interesting eyes she has” or “Hasn’t she got a nice smile”. In fact, Emma had the look of a young Elizabeth Taylor about her, with dark ringlets, a retroussé nose and almond-shaped eyes, one of which was a piercing blue and the other an equally striking green. So she had all that in her favour when she crossed the threshold of Mrs Brown’s establishment with her hand firmly clasped by her mother in case she considered running away.

Mrs Brown greeted Emma and her mother effusively, ushering them into the main classroom. Emma clearly liked her immediately and Emma’s mother could see rivalry for her affection looming.

“So, you’re Emma,” said Mrs Brown. “I’ve heard so much about you; come on in and join the other children. This is Emma, everyone, and she’s just had her fourth birthday.”

Emma wasn’t immediately sure where to sit, but she noticed that there was a spare seat next to a boy with dark, wavy hair and she thought he looked nice.

“I’m Danny, and I’m four,” he said.

“Hello, Danny,” Emma said. “I’m Emma. What does your daddy do?”

“He’s a Scottish laird and he’s got a castle.”

Emma was very impressed.

The class that morning was art, which is something Emma was quite good at, although she usually had her teddy bear to help her. Mrs Brown asked the class to draw a picture of a house with their mother, father and themselves in it. This was something of a conundrum for Emma. Her father wasn’t usually in the house as he was working, so she didn’t know whether to leave him outside; and her mother seemed to spend more time in the church than in the house. All of which meant that she’d have to draw a house with only teddy and herself in it, which would upset Mrs Brown and invite too many uncomfortable questions from her classmates. On the other hand, if Emma drew a full household, including teddy, she’d be defeating the purpose of the class, which Mrs Brown said was about expressing themselves. So, to cover all eventualities, Emma decided to draw houses on both sides of the paper.

Emma was quite proud of her drawings when they were completed. She thought she’d caught the mock Tudor design of her house very well and even her figures looked quite realistic. Mrs Brown came to her table and bent down to look at what she’d drawn.

“My dear, why are you in the house on your own?” Mrs Brown asked.

Emma glanced down, shocked. Mrs Brown was looking at the wrong side of the page. Danny sniggered. He’d turned the page over when Emma wasn’t looking. Emma decided she’d get him for that.

Emma turned over the page to show Miss Brown the intended drawing.

“Oh, that’s so much better,” said Mrs Brown. “You must really love your parents and you’ve drawn them so nicely.”

Next day, Emma and Danny were playing in the garden and trying to outdo each other climbing up the mulberry tree. Emma thought she had the edge of Danny but he rudely pushed her aside and almost made her slip. Emma glared at him and was surprised to see his eyes suddenly roll up in his face. Danny then lost his footing and fell about ten feet to the ground, landing heavily on his right arm. Emma scrambled down and ran into the house to find Mrs Brown.

“Mrs Brown! Mrs Brown!” she called.

“What is it, my dear?” said Mrs Brown, coming out of her study.

“Danny’s fallen out of the tree!” exclaimed Emma, bursting into tears.

“There, there, Emma,” said Mrs Brown, reassuringly, “let’s go see how he is.”

Mrs Brown discovered Danny lying on the ground, grimacing, and it was obvious he’d fractured his right arm.

“She did it, Mrs Brown!” said Danny, angrily. “She made me fall.”

“No, I didn’t, you pushed past me!” retorted Emma.

Danny’s parents and an ambulance were called. It was all put down to an unfortunate accident and Mrs Brown assured Danny’s parents that she’d improve playground supervision. Danny quickly forgot the incident and let Emma write her name on his plaster cast.

***

One day, in her second year at kindergarten, and for no particular reason, Emma timidly knocked on the door to Mrs Brown’s study whilst the rest of the class were playing outside. Not hearing anything, Emma opened the door and peered in. Mrs Brown had her back to Emma and seemed intent on something she was doing on a large table. Emma coughed and Mrs Brown turned around, appearing surprised by the intrusion.

“Yes, Emma,” she said, somewhat irritated, “what can I do for you?”

Emma noticed various intriguing items on the tables: a glass jar with something fluttering in it, a large wooden board with objects pinned to it and a collection of fragile looking things with iridescent colours, shimmering in the sunlight. She was transfixed.

“What’s that?” asked Emma.

Mrs Brown wasn’t really sure what to say. Lepidoptery wasn’t exactly part of the curriculum. Still, Emma obviously had an inquiring mind and it was better to be truthful than to send her away to spread rumours of insects done to death. “Emma, this is my hobby, I collect butterflies,” she said.

Emma looked closer. She saw butterflies with their wings spread out with pins fixing them to the board. “Have they gone to heaven?” she asked. “And what’s happening to the one in the jar?”

“Yes, Emma, these butterflies are dead, and this one – she pointed at the jar – is about to go to heaven.”

Emma looked surprised. “Did you kill the butterflies? How could you do that to something so beautiful?” She looked close to tears. Mrs Brown brought her closer to her and put her arm around her.

“Sometimes, Emma, it’s better to put things to sleep to preserve their beauty rather than letting it fade away.”

Emma nodded, not quite sure what to make of what she’d witnessed or what Mrs Brown had told her.