(4/13) Battles at Thrush Green (16 page)

Read (4/13) Battles at Thrush Green Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrush Green (Imaginary Place), #Pastoral Fiction, #Country Life - England

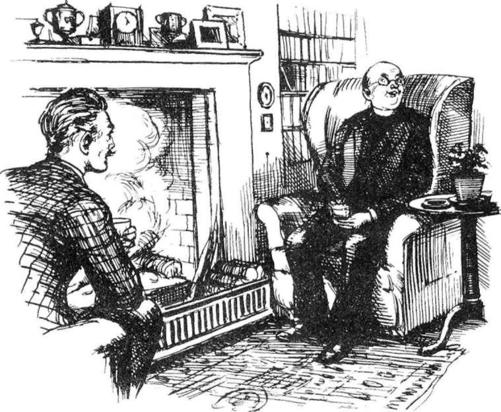

Charles was glad to settle by Harold's log fire, and to accept a small whisky and water.

He looked about the room appreciatively. There was a fine cyclamen on the side table, leather-bound books on the shelves, and a well-filled tantalus on the sideboard. Everywhere the hand of Betty Bell was apparent in the glossy furniture, the plump cushions, the shining glass.

'You manage to make things so very comfortable,' commented Charles. There was a wondering note in his voice. 'Somehow the rectory never achieves such snugness.'

Harold could hardly point out that good curtains and carpets were one of the basic requirements for soft living, and an ample income another, to supply other amenities, including first-rate domestic help.

'I have the advantage of lower ceilings, for one thing,' said Harold, 'and not such an exposed position. Those Victorian Gothic buildings never were designed for cosiness.'

'Dimity does wonders,' went on Charles, nursing his glass. 'When I think how bleak the house was when I lived there alone, I never cease to be thankful for her presence. Do you remember Mrs Butler who kept house for me?'

'I shall never forget her,' said Harold firmly. 'I have never, in all my travels, met a meaner, tighter-fisted old harridan.'

Charles looked shocked.

'Oh, I wouldn't say that,' he protested.

'Of course you wouldn't. But it's true. I remember the disgraceful way she allowed you to be neglected when you had flu, only bringing up a water biscuit or two when she deigned to climb the stairs! You were sorely put upon, you know that, Charles. Saints often are.'

'She was rather

frugal,

' admitted the rector. 'But why I mentioned her was that I heard by chance that she has married again.'

'Poor devil,' said Harold. 'I hope he belongs to a good club.'

'I really came,' said Charles, changing the subject tactfully, 'to have a word with you about this matter of the faculty. So far there are eight names on the list of objectors, but I fear that there may be some who object in their hearts but have not the courage to state so publicly.'

'In that case,' said Harold reasonably, 'they shouldn't worry you. I suppose you still want to go ahead and apply?'

'I do indeed. And so, of course, do most of the parochial church council members, as you know.'

'I believe we could get the churchyard taken over by the parish council, if that body were willing. It has been done elsewhere, and then of course the upkeep comes out of public funds.'

The rector put down his glass with a quick gesture of repugnance.

'I shouldn't dream of it,' he said sharply. 'Would you?'

'No, indeed. I think it is the church's business and should remain its responsibility.'

'Absolutely! Absolutely!'

'I only mentioned it as a way of solving our problem. Somehow, I didn't think you would jump at the idea.'

'My chief worry is two-fold,' said Charles. 'The village must agree about the matter, so that there are no grievances, and secondly, we must consider expense.'

'The faculty shouldn't run us into much more than ten pounds or so,' said Harold. 'The church funds can stand that all right.'

'I'm aware of that. What disturbs me is the possibility of a real battle in the village. If those eight objectors are truly all we have to contend with, then there's hope. But if, suddenly, more join the fight, we may even need to call in lawyers, and you know what that means!'

'It won't come to that.'

'Who can tell? I was talking to the vicar of my old parish at the Diocesan Synod last week, and their affair went to a hearing in the Consistory Court. The expense was astronomical. It depressed me very much.'

Harold took his friend's glass to the sideboard to replenish it.

'I still say, it won't come to that. We'll fight our own battle here at Thrush Green. I feel sure that we can talk to the objectors on their home ground, and get them – or some of them, anyway – to see things as we do.'

'You won't get Percy Hodge to,' said Charles, accepting the glass. 'He hasn't appeared in church since the meeting, and I fear that he is deeply hurt. The graves of his forefathers mean a great deal to him. It makes me very unhappy to see such bitterness.'

The rector sighed.

'Ah well, Harold. It does me good to talk over things with you. Somehow, they are never quite so bad after a gossip in this cheerful room.'

He prodded a log with the toe of a shabby shoe.

'Do you pay much for logs? he enquired.

Harold told him.

'And how much is coal?'

Harold told him that too.

Charles looked thoughtful.

'Perhaps that's why we so seldom have a

big

fire,' he said, quite without self-pity. 'Dimity deals with the bills to save me trouble, and so I hadn't quite realised how much a

big

fire costs.'

He stood up and smiled radiantly.

'But how lovely it is,' he cried. 'I can quite understand people practising

fire

worship. I'm a little that way myself, I believe!'

The night air was sharp as he crossed the green. Already the grass was becoming crisp with frost. Two miles away, at Lulling Station, a train hooted, and from Lulling Woods, in the valley on his right, an owl quavered and was answered by another.

His tall house loomed over him as he unlocked the front door. It looked gaunt and inhospitable, he realised. His thoughts turned on the conversation he had just had with Harold.

He found Dimity in the sitting-room, close to the fire. It was half the size of the one he had just left, he noticed, unusually observant. One could see the edges of the iron basket which held the fire. The coals were burning only in the centre of the container.

He looked aloft at the distant ceiling, and at the expanse of sparsely curtained window space. Although the night was still,

some

wayward draught stirred the light drapings.

The lamp by which Dimity was seated had a plain white shade which threw a cold light upon the knitting in her hands. Harold's shades, he remembered, were red, and made a cheerful glow.

'My dear,' he said abruptly. 'Are you cold?'

Dimity looked surprised. She put down her knitting, the better to study her husband.

'Why no! But you must be. Come by the fire.'

He threw off his coat and took the armchair opposite her, spreading his hands to the meagre warmth.

'I don't mean just now, my dear. Do you find the house cold? Habitually, I mean? Do you find it colder, say, than Ella's?'

'Much colder,' agreed Dimity, still looking puzzled. 'But naturally it would be. It faces north, and it's twice the size.'

'And we don't heat it as well, I fear,' said Charles.

'Ella always liked more heat than I did.'

'I've just come from Harold's. His fire seems enormous. I'm beginning to think we must give a very chilly welcome to visitors here. But my main concern is for you. You know that you tend to be bronchial. We really must keep a better fire, or see if we can put in some central heating of some sort.'

'Charles dear,' said Dimity, 'it simply can't be done. Do you know how much coal costs?'

'Harold told me. I couldn't help thinking that he must have made a mistake. Why, as a boy, I remember coal carts coming to the house with a large ticket displayed, saying two-and-six a hundred weight.'

'And that,' pointed out Dimity, 'was over half a century ago! Times have changed, and I'm sorry to say that Harold's figure is the correct one.'

'There must be many ways of making this place snugger,' argued Charles, looking about him with fresh eyes. 'What about a red lamp shade, like Harold's?'

'We could do that,' said Dimity, nodding.

'And a screen? My mother had a screen. She said it kept off draughts. And a sausage filled with sand at the bottom of the door. That would help.'

Dimity suddenly burst into laughter.

'Oh Charles! To see you as a domestic adviser is so funny! And such a change! What this house really wants is double-glazing, central heating, thick curtains and carpets, cellars stuffed with coal, and a log shed filled with nice dry logs. But we should need to find a crock of gold, my dear, to provide ourselves with all that.'

'But the shade,' pleaded Charles. 'And the screen?'

'We'll manage that, I think,' smiled Dimity. 'And I'll make the door sausage before the week is out. By the way, it's proper name is a draught-excluder.'

'Let's hope it lives up to it,' said Charles, recklessly putting two lumps of coal on the fire.

The subject still occupied Charles's mind later that night. Beside him, Dimity slept peacefully, but the rector could not rest.

There was no doubt about it, he was failing as a husband if he could not provide such basic things as warmth and shelter for his wife. It was not fair to expect Dimity to put up with such discomfort. He was used to it. He hardly noticed it, unless it was drawn to his attention, as it had been that evening, by the contrast between Harold's circumstances and their own.

Well, he supposed that he could look out for another, better-paid, living; but the thought appalled him. He loved Thrush Green, and now that he had embarked on the churchyard venture it would seem cowardly to run away from it and all its many problems.

Then there was the possibility of part-time teaching at the prep school in Lulling which Paul Young attended. Charles was friendly with the headmaster, and he recalled now that only a week or two earlier he was saying that he was looking out for someone to take Religious Instruction. No doubt, he had been sounding him out, thought Charles, but at the time he had not realised that, in his innocence.

But would it bring in any reasonable sum? And how much of that would be taken away in tax? And had he really the time to pay three or four visits a week to the school? His parish was an extensive one, and he took sick-visiting seriously. It was one of the qualities which endeared him to his flock.

The poor rector tossed unhappily. Something must be done. He had certainly been failing in his duty towards Dimity. Because she was so uncomplaining, he had let things slide.

'Sins of omission!' sighed Charles, thumping his pillow. 'Sins of omission! They must be rectified.'

He fell asleep soon after three o'clock, and dreamt that he was stuffing a red draught-excluder with sausage meat.

14 Dotty's Despair

A

S

the end of term approached, the preparations for the nativity play made uneasy progress.

Miss Watson turned a blind eye and a deaf ear to the protests of her truculent staff, but some points had to be conceded.

For one thing, Miss Fogerty refused point blank to try to train the infants in speaking parts. They were too young for it. They would be unreliable and let the others down. They could sing the carols at the end of the performance and she was quite willing for them to take non-speaking parts, such as oxen and asses and so forth, which were well within their capabilities, but the speaking cast must come from the junior school.

When little Miss Fogerty adopted this militant attitude, Miss Watson knew that she must give way. Dear Agnes was usually so co-operative, but there was no doubt about it, she had not been her usual tranquil self this term, and it would be as well to humour her.

Consequently, the long desk at the side of the infants' room was piled high with animal masks of extraordinary variety. The most life-like was one made by an artistic young mother who had adapted an oblong box, which had once held sticks of chalk, into a splendid muzzle for a cow. With a head-dress of magnificent horns, her daughter was the envy of the class.

There were several donkeys, recognisable mainly from their long ears, although most of them drooped so pathetically that Miss Fogerty privately thought that they looked more like the Flopsy Bunnies. However, the mothers would form the most important section of the audience, and the eyes of these beholders would see only beauty and delight.

To Miss Watson's secret dismay, Miss Potter was being extremely awkward about using the terrapin hut for the performance. She ignored her headmistress's requests to take down models, remove sand trays, dismantle the nature table and generally clear away such obstacles which would impede rehearsals. She also refused point-blank to attempt to make scenery of any sort. Miss Watson was nonplussed by this rebellious attitude.

'No one has scenery now,' the girl assured her. 'If we must have this play which, frankly, I think far too ambitious for these children, then the audience must imagine the settings. We were always taught at college that it was better training for the children to leave the stage clear for their own interpretations. Besides, where could we store the stuff? And who's to assemble it and take it down?'

There was much good sense in these remarks, but Miss Watson could not get over the fact that they had been expressed by a very junior member of staff to her headmistress. To give up the idea of the play was out of the question. Nevertheless, if it were to be done at all, it would have to be done, as Miss Potter said, without scenery.