(5/13) Return to Thrush Green (5 page)

Read (5/13) Return to Thrush Green Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #England, #Country life, #Pastoral Fiction, #Country Life - England - Fiction

'A time of hope,' commented Dotty to Floss who was busy licking a paw. 'We must remember that, Flossie dear. Let's trust that it augurs well for us too.'

Refreshed by her brief rest, she collected milk can and dog again, and made her way to see her old friend Ella Bembridge.

4 April Rain

MEANWHILE, at Ealing, Robert Bassett's mood changed from stunned shock to querulous fury, and finally to philosophic resignation. Milly, his wife, bore all with patience.

'The firm won't automatically crumble, my dear, just because you are away from the office,' she told him. 'Frank knows the ropes as well as you do, and has always coped during the holidays perfectly well. That old saying about no one being indispensable is absolutely true, so just stop worrying.'

Frank Martell had been with the firm all his working life, starting as office boy at a wage of twenty shillings a week, and soon promoted to thirty shillings a week when Robert Bassett had seen the boy's capabilities. He was now a man in his mid-forties, quiet, conscientious and absolutely trustworthy. To Robert he was still 'young Frank' despite the sprinkling of grey hairs round his ears, and Robert found it difficult to have to face the fact that he would have to give him full responsibility for the business during his own absence.

He felt better about the whole affair after Frank had spent an afternoon by the bedside going through a file of letters and orders. His grasp of affairs surprised Robert. Frank had never said much, and Robert had always been too busy to realise quite how much Frank knew of the running of the firm. His quiet confidence reassured the invalid, and when Milly returned to the bedroom, after seeing Frank out, she found her husband breathing more easily and looking very much more relaxed.

'He's done you good,' she commented. 'You'll sleep better tonight.'

'I believe I shall,' agreed Robert.

Milly brought him an omelette at half-past seven, and for the first time since the onset of his illness he emptied his plate.

When she had gone, he lay back upon the pillows contentedly. The door was propped ajar, and darkness was beginning to fall. He felt as he had as a child, secure and cosseted, with the door left open for greater comfort, and access to grown-ups in case of emergency.

His gaze roamed over the shadowy room. How little, over the past years, he had noticed the familiar objects around him!

He looked nbw, with renewed awareness, at these old inanimate friends. There, on the dressing-table, stood the shabby oval leather box containing the two splendid hairbrushes which his father had given him on his twenty-first birthday. They were still in daily use, but had far less hair to cope with these days.

Nearby stood the photograph of Milly as he first saw her, hair parted demurely in the middle, eyes upraised soulfully, and never a hint of a double chin. To his mind, she was better looking now, plump and white-haired, her complexion as peach-like as when they first met, and the tranquillity, which had first attracted him, as constant as ever. He had been lucky in his marriage, and lucky to have two beautiful daughters.

On the wall opposite the bed hung a fine print of the Duomo of Florence. They had spent their honeymoon in that city, staying at a quiet hotel which had once been an ancient family home, not far from the cathedral. They had always promised themselves a return visit to that golden city, but somehow it had never happened.

'If I get over this,' said Robert aloud, 'I'm damned if we don't do it. That's the worst of life. One is everlastingly putting things off until it's too late.'

He smoothed the patchwork bedspread. Here was another reminder of the past, for Milly and the two girls had made it together, before marriage had taken them away from home to Thrush Green. Robert had teased them, he remembered, about ever finishing it. They must have spent three winters on the thing, he thought, now tracing the bright hexagons of silk with a finger.

Most of the furniture had come from his own shop, but the bedside table had stood beside his parents' bed. He remembered it well, at the side of his widowed mother during her last long illness, laden with medicine bottles, books and letters, much as it looked now, he thought, with a mild feeling of shock. Well, it had served the generations loyally, and no doubt would continue to be used by his children and grandchildren. There was something very comforting in this quality of permanence. It put into perspective the brief frailty of man compared with the solid works of his hands.

Yes, here, all around him stood the silent witnesses of his life. He was glad to have had this enforced breathing space to acknowledge his debt to faithful old friends.

He slid farther down the bed, sighing happily. When his wife came with hot milk at ten o'clock, she found him in a deep sleep, and crept away again, with a thankful heart.

The last few days of April brought torrential rain to Thrush Green. It drummed on the tarmac of the roads and the school playground, with relentless ferocity, so that it seemed as though a thousand silver coins spun upon the ground.

It cascaded down the steep Cotswold roofs, gurgled down the gutters, and a miniature river tossed and tumbled its way down the steep hill into Lulling High Street.

At the village school, rows of Wellington boots lined the lobby, and mackintoshes dripped from the pegs. Playtimes were taken indoors. Dog-eared comics, incomplete and ancient jigsaw puzzles, and shabby packs of cards were in daily use, much to the children's disgust. They longed to be outside, yelling, running, leaping, fighting, and generally letting off steam, and would willingly have rushed there, despite the puddles and the downpour, if only their teachers had said the word.

Miss Fogerty, rearranging wet and steaming garments on the radiators, was thankful yet again for the comfort of her new classroom. At least her charges were able to pay their frequent visits to the lavatories under the same roof. In the old building it had been necessary to thread a child's arms into its mackintosh sleeves (invariably needing two or more attempts) before allowing it to cross the playground during a deluge. Really, thought Miss Fogerty, life was now very much simpler.

Next door to the village school, Harold Shoosmith, a middle-aged bachelor, struggled to locate a leak which had appeared in the back bedroom. He stood on a ladder, his head in the loft and a torch in his hand, while Betty Bell, his indefatigable daily help, stood below and offered advice.

'You watch out for bats, Mr Shoosmith! They was always partial to that loft. I remember as a girl the old lady as lived here then used to burn sulphur candles to get rid of them. Can you see any?'

'No,' came the muffled reply.

'You want a bucket for the drips?'

'No. I can't see a dam' thing.'

'You want another light? A candle, say?'

There was no answer, but Harold's trunk, then his thighs, and lastly his well-burnished brogues vanished through the trap-door, and thumps and shuffles proclaimed that the master of the house was surveying the highest point of his domain.

Betty Bell transferred her gaze from the gaping hole above her to the view from the streaming window. Rain slanted across the little valley at the back of the house, where Dotty Harmer's cottage glistened in the downpour. The distant Lulling Woods were veiled by rain, and the grey clouds, barely skimming the trees, told of more to come. She was going to have a wet ride home on her bike, that was sure.

'Found it!' came a triumphant call from above. 'It's running down one of the rafters. Get a thick towel, Betty, and a bucket, and I'll fix up a makeshift arrangement.'

'Right!' yelled Betty, 'and I'll put on your dinner. You'll need something hot after mucking about up there.'

She descended the stairs and caught a glimpse of a very wet Thrush Green through the fanlight of the front door.

Across the expanse of puddles Winnie Bailey was battling her way towards Lulling with her umbrella already dripping.

'Never ought to be out,' thought Betty. 'At her age, in this weather! She'll catch her death.'

But Winnie was quite enjoying herself. There was something very pleasant in splashing along under the shelter of Donald's old umbrella. It was very old, but a beautiful affair of heavy silk and whalebone, and a wide band of solid gold encircled the base of the handle. It was certainly far more protection from the rain than her own elegant umbrella, which was smaller and flatter, and which she resolved to keep-for ornament rather than use in future.

There were very few people about, she noticed, as she descended the hill to Lulling. Hardly surprising, in this weather, but what a lot they were missing! The stream of surface water gushed and gurgled at her side. Silver drops splashed from trees and shrubs, and a fresh breeze whipped the colour into her cheeks. It was an exhilarating morning, and she remembered how much she had loved a boisterous day when she was a child, running with arms thrown wide, mouth open, revelling in the buffeting of a rousing wind.

She was on her way now to visit three old friends, the Misses Lovelock, who lived in a fine house in the High Street. They were making plans for one of Lulling's many coffee mornings, and although Winnie tried to dodge as many of these occasions as she could, the proposed effort was for a cause very dear to her heart, and that of her late husband's, the protection of birds.

If the three sisters had been on the telephone, Winnie might have been tempted to ring up and excuse herself on such a wet morning, but she was glad that the Lovelocks considered a telephone in the house a gross extravagance. She would have missed this lovely walk, she told herself, as she approached their door.

The sisters were, in fact, very comfortably off, but they thoroughly enjoyed playing the part of poverty-stricken gentlewomen. Their house was full of furniture, porcelain and silver objects which would have made the gentlemen at Sotheby's and Christie's pink with excitement. A great many of these exquisite items had been begged for by the mercenary old ladies who had brought the art of acquiring other people's property, for nothing or almost nothing, to perfection. They were a byword in Lulling, and newcomers were warned in advance, by those luckless people who had succumbed in a weak moment to the sisters' barefaced blandishments.

Winnie had been invited to coffee, and was quite prepared for the watery brew and the one Marie biscuit which would be presented to her on a Georgian silver tray.

She was divested of her streaming mackintosh and umbrella in the hall, the Misses Lovelock emitting cries of horror at her condition.

'So brave of you, Winnie dear, but

reckless.

You really shouldn't have set out.'

'You must come into the drawing-room at once. We have

one bar

on, so you will dry very nicely.'

Miss Bertha stroked the wet umbrella appreciatively as she deposited it in a superb Chinese vase which did duty as an umbrella stand in the hall. There was a predatory gleam in her eye which did not escape Winnie.

'What a magnificent umbrella, Winnie dear! Would that be

gold,

that exquisite band? I don't recall seeing you with it before.'

'It was Donald's. It was so wet this morning I thought it would protect my shoulders better than my own modern thing. As you can guess, I treasure it very much.'

'Of course, of course,' murmured Bertha, removing her hand reluctantly from the rich folds. 'Dear Donald ! How we all miss him.'

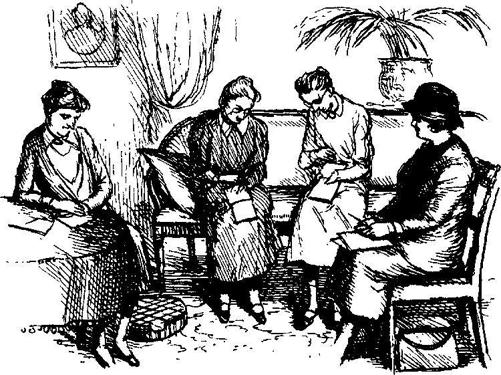

The ritual of weak coffee and Marie biscuit over, the silver tray and'Sèvres porcelain were removed and the ladies took out notebooks and pencils to make their plans.

'We thought a Bring and Buy stall would be best for raising money,' explained Violet. 'We can use the dining-room, and Bertha took a lot of geranium and fuchsia cuttings last autumn which should sell well, and Ada has made scores of lavender bags from a very pretty organdie blouse which was our dear mother's.'

'Splendid,' said Winnie, stifling the unworthy thought that these offerings would not have cost her old friends a penny.

'And Violet,' chirped Ada proudly, 'has made dozens of shopping lists and jotters from old scraps of paper and last year's Christmas cards. They really are

most

artistic.'

Violet smiled modestly at this sisterly tribute.

'And we thought we might ask Ella for some of her craft work. She has managed to collect a variety of things, I know, over the years. Would you like to ask her to contribute? It would save us calling in.'

'Of course,' said Winnie, 'and Jenny and I will supply all the home-made biscuits to go with the coffee, if that suits you.'

The Misses Lovelock set up a chorus of delight. Pencils moved swiftly over home-made notebooks and all was joy, and comparative warmth, within, as the rain continued to pelt down outside.

Albert Piggott, standing in the church porch with a sack draped, cowl-wise over his head, gazed at the slanting rain with venom.

He took the downpour as a personal affront. Here he was, an aging man with a delicate chest, obliged to make his way through that deluge to his own door opposite. And he had a hole in the sole of his shoe.