(5/20)Over the Gate (11 page)

She remembered, in a flash, that she had heard of his marriage during the war, but no further details. Lily Parker had risen above the station of the Blundes and had not passed on news of this family to Elsie.

'I'm still living at the old house,' said Elsie. 'Where are you now?'

'Near Southampton,' said John Blundell, falling into step beside her. 'I've a small shipping business there.'

'Alone?' asked Elsie, probing gently.

'No, I've two sons, both married now. They help me to run it. They're good boys.'

They emerged from the yew-flanked gateway into the village square. A beautiful glossy car was waiting near the railings of the village school which they had both attended so long before.

'I'll run you back, if I may,' said the man. They drove at a sedate pace to Elsie's home.

'Do have some tea with me,' said Elsie. 'You don't have to hurry back, do you?'

He must not be too late, but he would love some tea, he said. They talked until it was half past six, and during that time Elsie learnt that he had married an Italian girl whose father was in an Italian shipping line and was a man of some substance. Their two sons were born in Italy. They had come back to England for the boys' schooling. The climate had not suited his wife but she refused to leave him during the winters to run the business alone, and had contracted Asian 'flu, five years before, which had proved fatal.

It was apparent that he had loved her dearly. His voice shook as he told the tale in the shadowy firelit room and Elsie was reminded of his early tears when she had so light-heartedly turned him down at the tender age of seven.

This was the first of many meetings. Elsie knew, before a month had gone by, that this would end happily. Despite local tales to the contrary, Elsie did not pursue John Blundell. There was no necessity. There was mutual attraction, affection and need. Before the end of February they were engaged, and the marriage was arranged to take place after Easter. To Elsie it seemed wonderfully fitting that her first suitor should also be her last.

'And so, you see,' said Amy, 'it all ended happily. Elsie adores the boys and the first one is going to live at the old house at Bent with his wife and children. Elsie and John want something smaller, and I think they both want to be at a little distance from Bent. Everyone says they're tremendously happy, even though they are, well-somewhat

mature.

'

Amy eyed me speculatively. I returned her gaze blandly.

'Funnily enough,' I said, 'I had my first proposal at the age of seven. I was fishing for frogs' spawn at the time. Not a very glamorous pursuit, when you come to think of it.'

Amy leant forward with growing interest.

'What happened to him? Do you ever hear?' Clearly, she was hoping that history would repeat itself.

'I heard only the other day,' I told her. 'He's doing time for bigamy.'

6. Black Week

I suppose everyone encounters periods when absolutely everything goes wrong. The week after my friend Amy's visit was just such a one, and left Fairacre village school and its suffering headmistress sorely scarred.

On Monday morning I awoke to find that there was no electricity in the house. I am not a great breakfast-eater and can face a plate of cornflakes with cold milk as bravely as any other woman on a bleak March morning. But it is very hard to go without a cheering pot of tea, and this I saw I should have to do, for the clock stood at twenty to nine—inevitably, I had overslept—and the oil stove would not boil water in time.

A wicked north-easter cut across the playground. A few wilting children huddled in the stone porch.

'Go inside!' I shouted to them, as I bore down upon them.

'Can't get in!' they shouted back. I joined the mob. Sure enough, the great iron ring which lifts the latch faded to admit us.

'Mrs Pringle's inside, miss,' said Ernest.

'Well, why didn't you knock?' I asked, mystified.

'She don't want us mucking up her floor, she says.'

'What nonsense!' I was about to exclaim, but managed to bite it back. Instead I hammered loudly with the iron ring. After some considerable time, during which icy blasts played round our legs and blew our hair all over our faces, there was the sound of shuffling footsteps, the grating of a key, and Mrs Pringle's malevolent countenance appeared in the chink of the door. I widened the crack rapidly with a furious shove and had the satisfaction of hearing a sharp bang occasioned by the door meeting Mrs Pringle's kneecap.

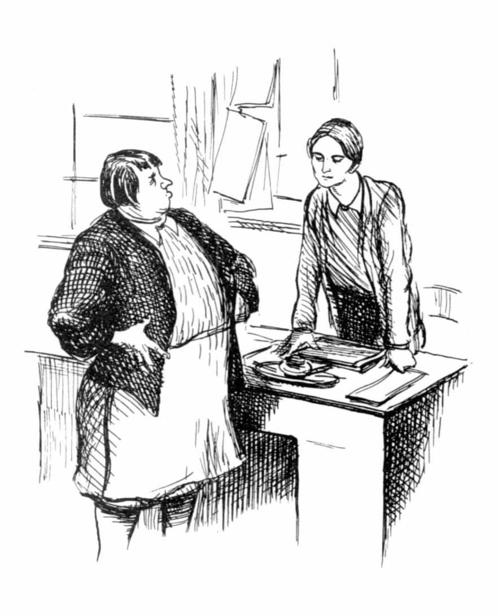

'Can I have a word with you?' I said with some asperity, ignoring her closed eyes and martyred expression. The children surged past us to their pegs in the lobby, and I went through to my room followed by Mrs Pringle. As I guessed, her limp was much in evidence. I hoped that this rime the affliction was genuine. Judging by that crack on the kneecap, it might well be.

'I have asked you before, Mrs Pringle,' I began In my best schoolteacher manner, 'to leave the door open when you arrive so that the children can come inside. It isn't fit for them to be out in this weather."

Mrs Pringle arranged a massive hand across her mauve cardigan and gasped slightly. She replied with an air of aggrieved dignity.

'Seeing as the lobby floor was wet I didn't want the children to catch their deaths in the damp atmosphere,' began the lady, with such brazen mendacity that I felt my ire rising.

'Mrs Pringle,' I expostulated, 'you know quite well that you locked the door because you wanted to keep the floor clean.'

Mrs Pringle's martyred expression changed suddenly to one of fury.

'And what if I did? Mighty little thanks I gets in this place for my everlasting slaving day in and day out. What's the good of me washing the floor simply to have them kids mucking it up the minute it's done, eh?'

Fists on hips she thrust her face forward belligerently.

'And what's more,' she continued, in a sonorous boom audible to all Fairacre, 'you've no call to give me a vicious hit like you done with the door. My knee's almost broke! I could have you up for assault and battery, if I was so minded!'

'I'm sorry about your knee,' I said handsomely. 'Of course, if you'd left the door unlocked there would have been no need to push our way in.'

'H'm!' grunted Mrs Pringle, far from mollified. 'No doubt I'll have to lay up with this injury, and with the stoves drawing so bad as they are with the wind in this quarter

someone's

going to find a bit of trouble!'

She limped heavily from the room, wincing ostentatiously.

For the rest of the day she maintained an ominous silence. I can't say I let it worry me. Mrs Pringle and I have sparred for many a long year and I know every move by heart. Now I confidently awaited her notice, and was rather surprised when it was not forthcoming.

The wind was fiendish all day. Every time the door opened, papers whirled to the floor. The partition developed a steady squeak as the strong draught shook it, and the door to the infants' lobby made the whole building shudder every time an infant burst forth to cross to the lavatory.

During afternoon playtime, when my back was turned for three minutes, Patrick, trying to shut the windows with the window pole lost his balance and broke an upper pane, bringing down a shower of glass upon the floor and a shower of invective upon himself. Now we had an even fiercer draught among us, accompamed by banshee wailing among the pitch pine rafters. We were all glad when it was time to go home.

Mrs Pringle, black oilcloth bag swinging on her arm, stumped into the lobby as I went out. She stared stonily before her and did not deign to answer my greeting. Past caring, I fled through the wind to die haven of my little house, craving only peace and tea.

On Tuesday I woke to hear the hiss of sleet on my bedroom window. The playground was white, and the branches of the elms swayed in the same wicked north-easter. Luckily, the electricity was functioning again, and after breakfast I made my way back to the school to see if the stoves were doing well.

They were not going at all. Mrs Pringle, with devilish riming, was going to give in her notice this morning, I could see. Meanwhile, sleet and snow blew energetically through the broken pane, and the usual cross-draughts stirred the papers on the walls.

Mr Willet arrived as I was lighting the stove in the infants' room. His face was red with the wind's buffeting, and his moustache spangled with snowflakes.

'Here, I'll do that,' he said cheerfully. 'They tell me her ladyship's gone on strike again.'

'I'm not surprised,' I said, and told him about yesterday's fracas.

'She's a Tartar,' commented Mr Willet. 'But never you fear, we'll manage without her. Soon as these ere stoves is drawing I'll paste a bit of brown paper over that there broken window. Best tell the Caxley folk to come and do a bit of glazing, I suppose. That's too high for me to manage this time.'

The children arrived. Ernest handed me a note. The handwriting was Mrs Pringle's.

'Am laid up with my damaged knee,' it said. 'Doctor is coming today and may say give in my notice. Will let you know. Matches is short.

Mrs Pringle.'

Matches were not short, they were non-existent, as I had discovered, but by now the stoves were going, in a sullen black mood, and little puffs of smoke occasionally escaped from them. Mrs Pringle had been correct about their dislike of a north-east wind. The stoves resented it as much as we did. As the fuel grew warm the smoke increased, and we worked throughout the morning amid lightly-floating smuts and eye-watering fumes.

Mr Willet, working perilously on an inadequate ladder as he blocked up the hole in the window pane, left his lofty perch now and again to survey the stoves.

'Beats me,' he said, scratching his head. 'I'll bet Mrs P. put the evd eye on 'em before she left!'

It seemed more than likely.

In the afternoon Eileen Burton complained of a stiff neck. I was about to dismiss this as a result of the draughts, but observing her flushed appearance I took her temperature. It was over a hundred, her neck glands were painful and she had not had mumps. I surveyed her anxiously.

'But my cousin's just had them,' she told me. 'And we often plays together.'

There was nothing for it but to wrap her up warmly, put her in my car and run her home at playtime. How many more, I wondered, peering through the gloom of the smoke-filled room on my return, would succumb in the next few days?

The sleet had changed to heavy snow by Wednesday morning, but mercifully the wind had dropped and the stoves behaved themselves.

The relief was tremendous, and I began to enjoy school without Mrs Pringle's presence. But the snow brought its own problems. The children were excited and fussy, quite incapable of working for more than three consecutive minutes, and standing up to look out of the windows whenever it was possible to see 'if it was laying.'

'Eggs or bricks?' I asked them tartly, but, quite rightly, they did not rise to this badinage and I was forced to give an elementary grammar lesson, in the middle of a spirited account of Moses in the bulrushes, knowing full well that neither would bear much fruit.

The snow was certainly 'laying'. It was coming down thick and fast, large snowflakes whirling dizzily and blotting out the landscape as effectively as a fog. It was nearly six inches deep by midday, and the dinner van was remarkably late. Surely there were no drifts yet, I thought to myself, to hold up Mrs Crossley on her travels? She was usually at Fairacre between half past eleven and twelve, having only Beech Green's dinner to deliver before returning to her depot.

At twelve the children who go home to dinner departed. There was still no sign of the van and I was beginning to wonder if I should telephone the depot when Patrick came running back to school, followed by the rest of the home-dinner children, all in a state of much agitation.

'Mrs Crossley's slipped over,' shouted Patrick.

'And spilt all the gravy,' shouted another. He seemed to think that the loss of gravy was more important than Mrs Crossley's accident.

'She's hurt her leg,' volunteered a third.