(6/13) Gossip from Thrush Green (12 page)

Read (6/13) Gossip from Thrush Green Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #Country life, #Thrush Green (Imaginary Place), #Pastoral Fiction, #Country Life - England

A plump middle-aged lady showed him into Justin's office on the left-hand side of the hall, and he was greeted affectionately.

'Just let me set you a chair, padre,' said Justin. 'Not that one. Take this, it has a padded seat.'

He levered up a heavy chair with a high Jacobean-type back and a seat upholstered in leather which was so old and rubbed that it resembled suede. It was, as Charles found, surprisingly comfortable.

'Tea now, I think, Muriel,' said Justin to the plump lady.

'Yes, sir,' she said, so humbly that Charles would not have been surprised to see her genuflect, or at least pull her forelock had she had such a thing. Obviously, Justin was the master in this establishment.

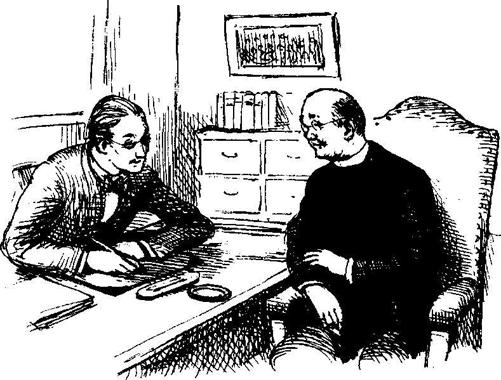

Well now, just tell me the trouble,' began Justin, when the door had closed.

Charles gave a remarkably concise account of his actions before and after the fire, and explained his position as a tenant of Church property.

Justin listened carefully, his fingertips pressed together. He watched his client over his half-glasses and thought how rare and pleasant it was to be face to face with an absolutely honest man.

A discreet knock at the door heralded the arrival of Muriel with the tea tray. It was lowered reverently upon a vacant space on Justin's desk.

The good rector, had he given any thought to the matter, would have been grateful for a mug of ready poured out tea with perhaps a bowl of granulated sugar with a well-worn teaspoon stuck in it. He was much impressed with the elegant apparatus now before Justin.

Two delicate china cups stood upon a snowy linen tray cloth. An embroidered satin tea cosy covered a silver teapot, and small cubes of sugar, accompanied by silver clawed sugar-tongs, rested in a matching bowl. Some excellent shortbread fingers were ranged alongside.

'Well!' exclaimed Charles happily, 'I really didn't expect such a beautiful tea! And what a handsome tea cosy!'

'It is rather nice, isn't it?' agreed Justin, surveying it as though he had just noticed it. 'One of the girls in the office ran it up one Christmas. And the tray cloth too, I believe. Very good with her fingers obviously. A slice of lemon, Charles, or milk?'

'Milk, please. Do you usually have time for tea? I hope you haven't gone to all this trouble on my behalf.'

'From four to four-thirty is teatime,' replied Justin firmly. 'I only see old friends then whom I like to invite to share my tea tray. Try the shortbread. Muriel makes it for me weekly.'

The rector could not help thinking in what a civilised way Justin seemed to conduct his business. He had no doubt that just as much work got done in the leisurely framework of Justin's day as was accomplished by so many feverish young men rushing from one thing to another.

'Of course, we have always stayed open until six o'clock,' said Justin, submerging his lemon slice gently with his teaspoon. 'So many of our clients appreciate being able to call here after their work is over. One needs a cup of tea to refresh one towards the end of the day.'

'Very sensible,' agreed Charles, dusting shortbread crumbs as unobtrusively as possible from his clerical grey trousers.

Over the tea tray Justin dealt with the rector's anxieties, and assured him that all would be satisfactorily arranged with the insurance people, the Church authorities, and all other interested parties in this sad affair.

It was exactly twenty-eight minutes past four when he rose and shook his old friend's hand in farewell.

'By the way,' he said, on his way to open the door, 'I am retiring at the end of this year.'

'You can't be!' exclaimed Charles. 'Why, you know you are always referred to as "young Mr Venables"! Who will take over?'

'Young Mr Venables will be seventy next birthday,' smiled Justin, 'and the boys here are in their forties and fifties. Plenty of good fellows to carry on at Twitter and Venables, believe me.'

'I can't take it in,' confessed Charles. 'Of course, I shan't mention this until you give me permission to do so.'

'You have it now, my dear fellow. There's no secret about it. Now, I mustn't keep you.'

He opened the office door, and saw Charles out into the sunshine.

The rector retraced his steps in thoughtful mood, pondering on Justin's decision to retire. Seventy next birthday, he had said. Well, perhaps he was right to leave the somewhat gloomy office and to feel free to enjoy his fishing and his golf when the sun shone. Certainly, Justin had served the little town well, as had his father before him. No doubt the middle-aged boys would carry on the good work, but it wouldn't please his old clients.

A car drew alongside the kerb just as Charles was approaching the Misses Lovelocks' house. It was driven by the vicar of Lulling, the Reverend Anthony Bull, and his mellifluous voice floated across the warm air.

'Get in, Charles, if you are making for home. I'm off to Nidden.'

Charles was rather looking forward to walking home in the spring sunshine, but it would have been churlish to turn down this offer, and in any case, he always enjoyed Anthony Bull's company.

He was a tall handsome man with a fine head and expressive hands. As a single man he had fluttered many maiden hearts, and even now, happily married as he was to a rich wife, a steady supply of embroidered slippers, hand-knitted socks, and useful memo pads decorated with last year's Christmas cards, flowed into the vicarage from adoring members of his congregation.

'We only got back from a few days in Devon yesterday,' said the vicar, 'and were appalled to hear about your house. I gather you are at Harold's for the time being, but if you want to come to us, Charles, the vicarage has plenty of room, and we should both be delighted to put you up.'

Charles thanked him sincerely. The vicarage was an elegant Queen Ann house, overlooking Lulling's extensive green. It was common knowledge that Mrs Bull's wealth had contributed to the comfort of their establishment. The beautiful old house had flourished under her cosseting, and Charles could not think of anywhere more lovely to shelter, if the need arose. He tried to say as much to the generous vicar.

'You've heard the rumour, I expect,' said Anthony Bull, 'about the re-organisation of the parishes around here? It's a case of spreading us rather more thinly on the ground, I gather. Nothing definite yet, but I shouldn't be surprised to hear that we are all going to play General Post before long.'

'Do you know,' said Charles, 'I haven't heard the game of General Post mentioned since I was a child! Nor Turn the Trencher, for that matter, nor Postman's Knock. Do you think people still play those party games?'

'I should like to think so,' responded the vicar, drawing up outside Harold's house on Thrush Green, 'but I fear they play rather more sophisticated games these days, with perhaps rather less innocent enjoyment.'

At that moment, Charles saw Dotty Harmer emerging from Ella's, milk can in one hand, and Flossie's lead in the other. He did not feel equal to coping with that lady, much as he admired and respected her.

He hurriedly got out from the car.

'Thank you again, Anthony, for the lift, and your very kind offer of help.'

The vicar waved and drove off towards Nidden. What a beautiful glossy car it was, thought Charles, without a trace of envy. It was fitting that such a fine fellow as dear Anthony should travel in such style, and live in such a splendid house.

He opened Harold's gate, and walked with a thankful heart into his own temporary abode.

9. Trouble At Tullivers

I

T

was soon apparent to the inhabitants of Thrush Green that young Jack Thomas departed from Tullivers each morning at eight o'clock. The shabby van took the road north towards Woodstock, and presumably from there he went to the estate office where he was employed.

His wife Mary and the other two residents were not seen until much later in the morning. The more censorious of Thrush Green's housewives deplored the fact that only once had Mary been seen to shake the mats, and that was at eleven-thirty in the morning. As for the nameless pair with the motor bicycle, they seemed to be invisible most of the time, although Ella reported that she had seen them having coffee one morning in The Fuchsia Bush, and later had noticed their vehicle propped outside the Job Centre in Lulling High Street. Were they proposing to settle locally, people wondered?

About a week after the fire, the peace of Thrush Green was shattered between eleven and twelve one starlit night, by the raucous sound of pop music and the throbbing of drums. Occasionally an ear-splitting shriek broke the rhythm, and above it all was the wailing of a nasal voice which might have been a woman's or a banshee's.

The downstairs lights at Tullivers were still ablaze at that time, and the noise certainly came from that house. Ella Bern bridge, some hundred yards or more away, was wakened by the din, and so were Isobel and Harold Shoosmith, equally far away.

'What the hell goes on?' muttered Harold, leaning out of his bedroom window. 'Thoughtless louts! They'll wake everyone at the Youngs' place, and I should think poor old Robert Bassett will be blown out of his bed at this rate.'

Robert Bassett and his wife were the elderly parents of Joan Young. Their home, converted from stables in the Youngs' garden, was one of the nearest houses to Tullivers. He had been very ill, and it was natural that Harold should be concerned first with his old friend's position so close to this shocking noise.

'I shall go and ring them,' said Harold firmly. Isobel heard him padding downstairs to the telephone.

There was a long wait, and then he returned.

'So much dam' racket going on they can't hear the bell,' he fumed. 'I've a good mind to ring the police.'

'Wait a bit,' urged his wife. It will only make more to-do if the police come. It may stop soon.'

'I doubt it,' said Harold grimly, but he shut the window, and got back into bed.

He was not the only one to telephone to Tullivers. Edward Young, outraged on his father-in-law's behalf, also failed to get through, and as he was just out of a hot bath, he did not feel inclined to traipse across to Tullivers to remonstrate in person.

Joan had been along to see her parents, and had found them quite cheerful and in bed. Philosophically, they had inserted the ear plugs which they always took with them when travelling, and they appeared less perturbed than their children.

Winnie Bailey had contented herself with viewing Jeremy's sleeping form and postponing complaints until morning. The cacophany ended about half past one. The lights went out at Tullivers. The residents at Thrush Green heaved sighs of relief, swore retribution at some more reasonable hour, and fell thankfully asleep.

Only Winnie Bailey's Jenny remained wakeful, and she was seriously considering the geographical advantages of Percy Hodge's farm house, should she ever be invited to live there. There was now no doubt that Percy was seeking a second wife, and was being uncommonly attentive to her.

Jenny, brought up in an orphanage and later a drudge - though a grateful one—to the two old people who had taken her in, could not help feeling touched by Percy's devotion. On the other hand, did she really want to marry at all?

Life at Thrush Green with kind Winnie Bailey held all the happiness that she needed. Never had she enjoyed such luxury as her own small flat overlooking the green. Winnie's companionship was doubly precious because she had never known such warmth and generosity of spirit. And how good she had been to her in this last illness! And then she loved the house they shared. It was a joy to polish the lovely old furniture, to set the kitchen to rights, to shine the windows, the silver, the brass. The thought of leaving Winnie and the fine old home which they shared was insupportable.

And yet—poor Percy! He certainly missed his Gertie, and he was a fine fellow still. She would be cared for if she threw in her lot with his, and did he not perhaps need her more desperately than Winnie did? Jenny's warm heart was smitten when she recalled the buttons missing from his jacket, and the worn shirt collar that needed turning. What a problem!

St Andrew's church clock chimed four, and Jenny heaved a sigh. Best leave it all until later! She'd be fit for nothing if she didn't get a few hours' sleep, and tomorrow she had planned to turn out the larder.

She pulled up the bedclothes, punched her feather pillow into shape, and was asleep in five minutes.

Harold Shoosmith rang Tullivers at seven-thirty next morning to remonstrate with young Jack Thomas before he left for work. The young man was as profuse in his apologies as can be expected from someone at that hour, only partially dressed, and attempting to get his own breakfast. It wouldn't happen again. They would make sure that all the windows were shut, and the volume kept down, during future rehearsals.

Before Harold had time to enquire further, the telephone went dead. Other residents rang later in the day but did not get quite as civil a response as Harold had received.

Winnie Bailey decided to call in person during the evening when, she supposed, young Jack Thomas would be home and would have had a meal after his day's work.