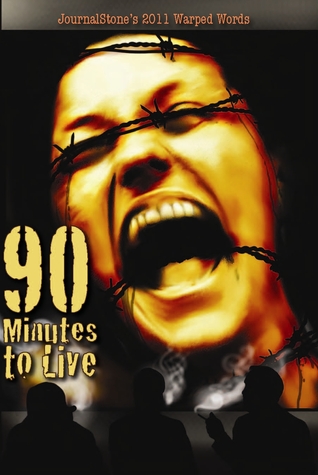

90_Minutes_to_Live

Read 90_Minutes_to_Live Online

Authors: JournalStone

JournalStone’s 2011

Warped Words

90 Minutes

to Live

Compiled By

Joel Kirkpatrick

JournalStone

San Francisco

Copyright ©2011 by Christopher C. Payne

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, names, incidents, organizations, and dialogue in this novel either are the products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously.

JournalStone books may be ordered through booksellers or by contacting:

JournalStone

199 State Street

San Mateo, CA 94401

The views expressed in this work are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

ISBN: 978-1-936564-33-0 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-936564-34-7 (dsj)

ISBN: 978-1-936564-35-4 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 201194318

Printed in the United States of America

JournalStone rev. date:

Cover Design: Denis Daniel

Cover Art: Philip Renne

Edited By: Elizabeth Reuter

Dedication

To Rocky Wood

Additional titles from JournalStone:

Shaman’s Blood

Anne C. Petty

The Traiteur’s Ring

Jeffrey Wilson

Jokers Club

Gregory Bastianelli

Ghosts of Coronado Bay

J.G. Faherty

Imperial Hostage,

Book 1 of the Destruction Series

Phil Cantrill

That Which Should Not Be

Brett J. Talley

Reign of the Nightmare Prince

Mike Phillips

Available through your local and online bookseller or at www.journalstone.com

John La Rue

Brad Carpenter

Bruce Golden

Jeffrey Wilson

Brett J. Talley

Jasmine Cabanaw

Timothy Miller

Bill Patterson

Peter Orr

Nu Yang

JG Faherty

David Perlmutter

Jennifer Phillips

(Science Fiction)

By

John La Rue

Smitty’s a good kid.

He ducks through the hatchways ahead of me; pops a corner, pretty good for anybody born after the war. A little over-eager maybe but I let him do it. There’s no need; this ship is dead already and so is everyone on it.

I

f

anyone is still here.

“Anything doing?” Captain Jaz buzzes us from back aboard the

Lancer

.

“No ma’am,” I report. “Empty hallways.”

It’s creepy. Dead ships always are and I’ve never gotten used to the big ones, even when they’re filled with

p

eople. A sp

a

ceship, to me, is a snug thing, wrapped as tightly around a spaceman as a phone around a battery.

But that was before. Back when dead ships stayed dead.

These days, the nanobots just keep chugging away till they run out of slag. Microscopic, mindless drones working from a schematic of the ship’s original layout, swarming invisibly over the hull to fill in dents and scratches, bridge gaps and repair systems. They’ll repair the ship all right—right back to mint condition even. Only question is whether you’re still alive when the fail-safes reset and life support kicks back on.

They market these boats as unsinkable. Indestructible. Set it and forget it—the ship that repairs itself! Sounds great in a pamphlet I guess. Fate repays us with ships like this one, the

Hannah Lee

, adrift in space with all its machinery ticking over. But somewhere in here I know there are bodies on the deck, rigid as they fell. Silence rings through the ship, end to end, with the click of our boots.

I keep expecting Linda to come around the corner. Keep hoping that she’ll tell me how glad she is to see me. That she’s sorry she ever left.

The

Hannah Lee’s

a luxury cruiser. A party boat. Two people can run it; two hundred could ride. Full-gravity decks, real showers, an inflatable ballroom puffed out of one side, that sort of thing. Gravity decks, can you believe it? Hell of an engine in here somewhere, to support all that.

Now it’s just empty, one hallway after another, gentle machines humming in the

b

a

c

k

g

r

o

u

n

d, doors hissing open in front of us with perfect automation.

“What the-” Smitty’s too sweet of a kid to swear in front of me, thinks I’m some kind of hero from the war. Like we

never

swore…. He stops just through the ballroom door. Any marine I ever met could’ve killed him from his right side, easy—he never looked and the blind spot on these pressure suits is like…an acre, even with the visor rolled back. I let it slide and duck past him into the ballroom.

The ballroom’s pretty swank,

if

y

o

u

a

s

k

m

e

.

Some kind of chandelier with prisms and the walls, though I know they’re some light polymer, look a hell of a lot like polished marble.

But it’s a ship that’s got Smitty’s attention. Shit, it’s a Betty, parked right there on the dance floor. Jesus H.P. Christ, a whole goddamn Betty, all in one piece.

“Didn’t you fly one of these, sir?” Smitty asks me, eyes shining.

A Betty’s the least ship a man can take into the sky. Two men, strapped back-to-back around a fuel core—gunner and pilot. You have no life support in there, just you and your suit. No gravity, no air and no eject button.

I went to battle in a Betty a half-dozen times, before me and Randy got promoted past the point of flying—promotion

b

y

v

i

rtue of survival we figured, caus

e

we never

met anybody else who brought back a whole Betty more than four times in a row.

But this one is intact, with the low-libido hull still wrapped in its black matte finish, stealth pinholes as unblemished as the day she was made. Believe me, we stopped making those damned machines before the war even ended.

“What gives?” Captain Jaz buzzes again.

“You won’t believe us,” Smitty says, “But there’s a Betty down here in the ballroom.”

“How many pieces?”

That’s the way they always came back. Pieces.

“Just the one,” said Smitty, “Shipshape, by the look of it. God, what a beauty.”

Something

is

wrong with this ship though. Something more than the echo of a pre-flight knot in my stomach. She’s uncanny, this one, unearthly, l

i

k

e

s

h

e

’s watching me. Ready to put her BB stinger through my pressure suit.

I shake it off.

“Let’s cut the chatter,” I snap—harder than I meant to, “Smitty, the lifeboats?”

He double-times downstairs, guilty, runs round the Betty to the far wall—

t

h

e

on

e

th

a

t

’

s hull p

l

a

t

i

n

g when the ballroom’s not inflated. “Both here,” he shouts up.

Well shit.

“Cap’n, is that all of ‘em?” I buzz Jaz, but I know the answer already.

“Yeah,” she says. “That’s all.” Jaz keeps the sympathy out of her voice but she has to know it’s a blow. No survivors then. No chance Linda got out before whatever happened here took down the ship and everybody on it.

“Now what?” says Smitty, coming back up the ladder.

“Look for bodies,” I say.

“Where?”

I just look him in the eye. Make him work it out himself. He plays with the open visor on his helmet as he thinks.

“I guess if my ship were busting up…I’d go for the life support first.”

I follow him back out of the ballroom, looking back at that damned Betty.

Now I’m glad Smitty’s going through hatches first. There are some things I don’t want to see.

It doesn’t take long.

“Got one Sir,” he calls back.

I can see the legs through the hatch. Can’t help but hold my breath.

Anyone but Linda….

It’s Taylor. Bent awkwardly, lying on his face.

“He died in null-G,” I observe.

“How you reckon?”

“Bend in the elbow,” I point. “Only rigor-mortis in Z-G gives you that twist. He died first and came down after, when our invisible friends got grav going again. A while after or he wouldn’t be stiff when he came down.”

Smitty nods. “Suffocation,” he says. I raise an eyebrow. His turn to explain. He only points. A facemask and a canister lie in the corner, gauge upturned and orange.

Both of us glance at our own gauges. Can’t help it.

Suffocation’s not a way I want to go,

w

a

t

c

h

i

n

g

t

h

e minutes tick down while you struggle harder and harder to draw enough breath.

I figure the first hour is fine. You try to solve whatever problem has you in a bind. You count on the bots to pull through with a repair, patch things up enough to save your sorry ass. Maybe you pray, if that’s your thing. After an hour, you start to worry. You tick into yellow on your gauge and start to panic. Then you hit orange. Then you die.

I shudder.

“Think it was a blowout?” Smitty asks.

“Possible,” I say. I pause a minute, thinking over whether I want to ask what’s on my mind. Oh hell. We came this far. “Your guys bring a forty-four?”

“A what?”

“An N-44,” I say but he doesn’t get it until I pantomime the hat.

“Oh!” says Smitty, “Oh sure! But ours is a 260. It’s

way

better-”

“Run get it, will you?” I cut him off.

“Bring it here, sir?” he asks.

“It’s where the stiff is, no?”

He goes.

The forty-four is a thing our guys cooked up during the war, back when we were still learning how to have a real good knockdown up here among the stars. The trouble was, you mostly had whole ships alive or whole ships dead. Never had wounded to tell you how things went bad, so a lot of our trouble-shooting schemes were entirely theoretical.

I turn Taylor over with my foot. His eyes stare up past me, gray.

I reach down and shut them, pull a clump of hair from his head. Funny how much y

o

u can tell from hair. It’s like a little chemical printout

of the last month of a man’s life. The air

he breathed, the water he drank, the food he ate—it’s all bound up in keratin and melanin and oil, laid down line by line as it creeps out of his scalp. They used to use the print to work out where a man had been, Earth or Mars or one of the stations. Wasn’t til

l

t

he war that somebody worked out you could cross-reference the readout with a scan of his cortex and the ship’s logs and get a good read on his state of mind in the closing moments.

Good enough to run a simulation. A resurrection, we mostly called it.

You’d see the MP’s sitting there with their headphones on, talking, asking questions, watching teletype scrawl across a little green screen, fifty characters at a time and listening close for that thin, flat voice, crackling through static from somewhere beyond.

I did a fair number of exit interviews myself. “Tell Sally I love her,” they’d say at the end. Or “Tell Mom I’m sorry.” It sticks with you, the idea everybody dies with something left unsaid.

Taylor—I’m not sure I want to do Taylor. I

never met the man, when he was alive. Just heard Linda talk about him. About his boat—this boat. About his plans for ion harvesters in the Beltway. About his damned haircut. It’s enough to know I resent him. His expiration doesn’t change that.

I hear something move in the hallway and fight back the unreasonable surge of hope it might be Linda, climbing out of some unknown safe room.

She’s dead, somewhere in here.

The noise is Smitty, hauling something that looks like a beige cabinet, balanced across a four-wheeled cart half its size and trailing a power cord down the hall.

“What the holy hell is that?” I ask.

“The 260,” he says. “It’s kind of a wall unit but you said to bring it over….”

If I’d known, I would’ve had him haul Taylor over to the

Lancer

. It would’ve been easier.

“Why’s it so damned big?”

The N-44 was a thin thing, like a skullcap made of plastic with copper lacework. It had a jack for the processor and another for the headset and that was about the whole deal. You plugged it into the ship’s data feed and the computer did the rest.

“It’s an all-in-one unit,” says Smitty, like a salesman. “You put the hair in there, the head and the hand,” he points to the different-sized holes in the thing.

“The hand?”

“Well, sure,” says Smitty, but he doesn’t look sure. “It gauges conductivity I think. And blood type. All that stuff.”

I shake my head. “Wouldn’t’ve worked in my day.”

“Sure it would’ve,” he says, “Works anywhere, any time.”

“Not if he doesn’t have a hand.”

I’ve seen a fair number of

t

hose in my day

.

Back in the first year of the war, the theory was that, in case of a blowout—when your ship’s got a hole in it and you’re losing air—the best thing to do was to sound an alarm, then

r

o

l

l

t

h

e

b

u

l

k

h

e

a

d

s

s

l

o

w

l

y

s

h

u

t

.

G

i

v

e

p

e

o

p

l

e

t

i

m

e

t

o

e

v

acuate.

But people didn’t evacuate. Not spacemen anyway, brave cusses that we were. We found all kinds of bodies mangled in the doorways or freeze-dried in the blown out room and it didn’t get any better

w

h

e

n

t

h

e

y

s

l

o

w

e

d

t

h

e

r

o

l

l

t

o

g

i

v

e

a

l

i

t

t

l

e

more evacuation time.