97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement (12 page)

Read 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement Online

Authors: Jane Ziegelman

Tags: #General, #Cooking, #19th Century, #History: American, #United States - State & Local - General, #United States - 19th Century, #Social History, #Lower East Side (New York, #Emigration & Immigration, #Social Science, #Nutrition, #New York - Local History, #New York, #N.Y.), #State & Local, #Agriculture & Food, #Food habits, #Immigrants, #United States, #Middle Atlantic, #History, #History - U.S., #United States - State & Local - Middle Atlantic, #New York (State)

© 1937 King Features Syndicate

Maggie and Jiggs’s high jinks inadvertently launched a chain of gastronomic events that transformed both the perception and reality of Irish-American food ways. In 1914, a New York saloon-keeper, James Moore, opened a restaurant on West 47th Street, in the city’s emerging theater district. In homage to Maggie and Jiggs, he called it Dinty Moore’s, the comic-strip tavern to which Jiggs is always sneaking off. Like the fictional version, the real-life Dinty Moore’s served homey cooking, but the crowd it attracted was distinctly upscale; theater and publishing luminaries, politicians, and, in later years, broadcasting executives. Having grown up in a rough-and-tumble Irish neighborhood, James Moore was catapulted into New York society, but, like Jiggs, he held tight to his culinary roots, proudly known as “the corned beef and cabbage king,” a dish that remained on his menu until his death in 1952.

Thus, in two very public forums—the comic strip and the restaurant—corned beef and cabbage became reattached to its Irish past. When Joseph and Bridget Moore lived at 97 Orchard Street, they would have marked St. Patrick’s Day with, perhaps, a dish of pig jowls, a common celebratory food among Irish East Siders. By the 1940s, during the lifetime of their great-grandchildren, corned beef and cabbage had become the mandatory St. Patrick’s Day meal. At the same time, the era’s food authorities denounced it as a culinary myth—a food pretending to be Irish that wasn’t Irish at all. To explain its prevalence among Irish-Americans, they invented a number of historic scenarios. In the one most oft-repeated, Irish-Americans were introduced to corned beef, a food unknown to them in Ireland, by their Jewish neighbors and adopted it as a cheaper substitute for their beloved bacon.

The story of corned beef illustrates a larger point: immigrants used food as a medium to express who they were and who they wanted to become. They used it to assert identity, and in some cases to deny it. In the nineteenth century, socially prominent Irish-Americans, like our well-heeled banquet guests, found it expedient to distance themselves from certain low-status foods. But as the immigrants’ social position evolved and anti-Irish feelings began to fade, the significance of their foods evolved too. The language of food, like any expressive medium, is never fixed but perpetually a work in progress.

The Gumpertz Family

O

ur visit with Mrs. Gumpertz begins on a Friday, late morning, over a steaming pot of fish, a carp. The fish lays snugly in an oblong vessel, like a newborn in a watery cradle. From our current vantage point, it looks intact. In reality, however, the fish has been surgically disassembled and reassembled. It is the kind of culinary operation worthy of the trained professional, yet the responsible party is standing in front of us, an ordinary home cook. The process begins with a slit down the backbone. Mrs. Gumpertz opens the fish the same way one opens a book. Carefully, she scrapes the flesh from the skin, chopping it fine so it forms a paste, what the French call a forcemeat. Reduced to a mere envelope, head at one end, tail at the other, it is now the perfect receptacle for stuffing. Mrs. Gumpertz fills the skin with the paste and sews it shut. She lays the reconstructed carp on a bed of fish bones and onion—sliced but unpeeled—then puts it up to simmer. Just now, she is standing over the open pot, wondering if it needs more time. She prods it with a spoon; the fish is ready. She lifts the pot from the stove, moves it to a chair in the parlor, and leaves it there to cool by an open window. Moments before sundown, start of the Jewish Sabbath, she slices her carp crosswise into ovals and lays them on a plate. The cooking broth, rich in gelatin from the fish bones, has turned to jelly. The onion skin has tinted it gold. Mrs. Gumpertz spoons that up too, dabbing it over the fish in glistening puddles. To a hungry Jew at the end of the workweek, could any sight be more beautiful?

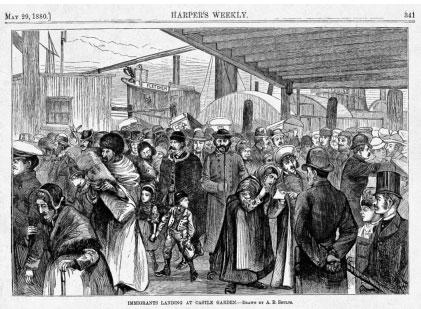

Jewish immigrants landing at Castle Garden, 1880.

Provided courtesy of HarpWeek., LLC

Twenty-two-year-old Natalie Reinsberg emigrated to New York from Ortelsburg, Prussia, in 1858. Her betrothed, Julius Gumpertz, another German Jew, had arrived a year earlier. Their wedding date is unknown, but their first child, Rosa Gumpertz, was born in New York in 1867. A second daughter, Natalea, known to the family as Nannie, was born in 1869, then Olga in 1871. The couple also had a son named Isaac, born in 1873, but he did not survive childhood. The family moved to 97 Orchard Street in 1870, when most of the building’s residents were German-born Catholics or Protestants, and remained on Orchard Street for the next fifteen years, as the neighborhood around them gradually shifted from Gentile to Jewish.

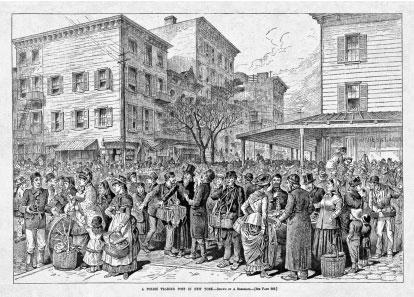

For Jews like the Gumpertzes, the Friday evening meal was reserved for fish, a tradition carried over from Europe. On the Lower East Side, the Sabbath fish tradition brought a stream of basket-wielding shoppers to the intersection of Hester and Norfolk streets, center of the Jewish fish trade in the 1890s. By this time, Hester Street was a full-blown pushcart market open every day except Saturday. The real action, however, began Thursday afternoon and peaked Friday morning, when Jewish women did their Sabbath marketing. This was prime time for the East Side pushcart vendor. Nineteenth-century New Yorkers who ventured downtown from the better neighborhoods above Fourteenth Street were flabbergasted by the scene awaiting them on market day: “There is hardly a foot of Hester Street that is not covered with people during the day. The whole place seems to be in a state of perpetual motion and the occasional visitor is apt to have a feeling of giddiness.”

1

At the corner of Norfolk Street, the shoppers reached maximum density, a solid throng of housewives sorting through wagons of perch, whitefish, and carp for the freshest, clearest-eyed specimens. But now we’re jumping ahead, beyond the scope of our present story…. Back in the 1870s, when the Gumpertz family moved to Orchard Street, East Side women bought their provisions from the public market on Essex Street or, perhaps, from one of the roving peddlers—some with baskets, others with wagons or carts—who patrolled the streets of Manhattan.

An illustration from

Harper’s Weekly

depicting the Hester Street pushcart market, 1884.

Provided courtesy of HarpWeek., LLC

The Friday evening fish recipe was determined by where exactly the immigrant was born. If she came from Bavaria, for example, the housewife stewed the fish in vinegar, sugar, a splash of dark beer, and a handful of raisins, the sauce thickened by a sprinkling of crumbled ginger snaps. This was the famous sweet-and-sour dish known on Gentile menus as carp, Jewish-style. Another possibility was carp in aspic. Here, the whole fish was cut into steaks, simmered with onion and bay leaf, then allowed to cool with its cooking broth. The choicest portion was the head, appropriately reserved for the head of the household. Or perhaps, if she had an expanded food budget, the German cook might prepare an aromatic stewed fish, the sauce enriched with egg yolk. Such recipes were memorialized in

The Fair Cook Book

, a collection of German-Jewish recipes published in 1888 by the women of Congregation Emanuel in Denver, Colorado.

The Fair Cook Book

is the first known Jewish charity cookbook published in America (the queen of the genre,

The Settlement Cook Book

, has sold over two million copies to date). The following recipe, contributed by Mrs. L. E. Shoenberg, a nineteenth-century Denver homemaker, combines the sweetness of ginger and mace, the creaminess of egg yolk and the piquancy of lemon:

S

TEWED

F

ISH

Cut a three-pound fish in thick slices and put on to boil, with one large onion sliced; salt, ginger, and mace to taste; cold water enough to cover fish, let boil about twenty minutes; take the yolks of three eggs, beat light, juice of two lemons, chopped parsley, beat well together. When fish is done pour off nearly all the water, return to fire and pour over your eggs and lemon, moving fish briskly back and forth for five minutes so that the egg does not coagulate.

2

But if the cook was a native of Posen in eastern Prussia, the Friday night fish might resemble Mrs. Gumpertz’s carp. It is the dish we know today, though in an altered form, as gefilte fish. The name “gefilte fish” comes from the German word

gefülte

, meaning stuffed or filled, since the original version was exactly that, a whole stuffed fish. Writing on the provenance of gefilte fish in the 1940s, the Jewish cooking authority Leah Leonard posed several possibilities:

Gefilte Fish may have originated in Germany or Holland sometime after the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. Or it may have been invented in Russia or Poland. Or, perhaps, it was only the culinary ingenuity of a housefrau-on-a-budget in need of a food stretcher. One thing is certain, Gefilte Fish is Jewish.

3

Across Central and Eastern Europe, one could find some version of gefilte fish wherever Jews had settled, prepared, like clockwork, Friday mornings, and served that evening with grated horseradish. Aside from matzoh or challah, few Jewish foods were as ubiquitous. Here was a food of towering stature in the Jewish imagination. Over the centuries, a body of mystical thinking had grown up around gefilte fish, explaining its perfection as a Sabbath delicacy. Because of its intricacy, the dish was also a perfect measure of the Jewish housewife’s culinary skill. No other food in the Jewish kitchen required as much time or finesse. Along with the Sabbath candlesticks, the oblong gefilte fish pot, a vessel dedicated to that one food, was among a handful of objects that the Jewish housewife carried with her to America.

Despite its Jewish resume, gefilte fish did not originate with the Jews. Rather, it was a culinary convert, a food taken from the Gentile kitchen and adapted by the Jewish cook sometime in the distant past. In this respect, it reflects a larger pattern true of many foods typically consumed by Jews, among the world’s most avid culinary borrowers. Where most cuisines are anchored to a place, Jewish cooking transcends geography. Spatially unmoored, it is the product of a landless people continuously acquiring new foods and adapting them as they move from place to place, settling for a time, then moving again.

Coming from Prussia, Mrs. Gumpertz was an Ashkenazi, a very elastic label that takes in the Jews of northern France, Germany, Austria, Romania, Poland, all of the Baltic countries, and Russia. Its original meaning, however, was more narrowly defined. Sometime in the tenth century, large Jewish families from southern France and Italy began to migrate north, forming settlements along the Rhine River. These were the original Ashkenazim, a term derived from the medieval Hebrew word for Germany. The early Rhineland communities were made up largely of rabbis and merchants. Both figures, it turns out, played major roles in shaping Ashkenazi food traditions. In the great centers of Jewish learning that sprang up in the Rhine Valley, rabbinic scholars directed their intellectual energies toward food-based issues, including the finer points of kashruth, Jewish dietary law. As interpreters of kashruth (which is ever-evolving), they decided which foods were fit for Jewish consumption, how they should be cooked, who was allowed to cook them, and when they should be eaten. Jewish traders, meanwhile, acted as culinary conduits, shuttling foods and food traditions from one side of the globe to the other. As the preeminent travelers of their day, they introduced medieval Europe to the exotic foods of the East: nuts, spices, marzipan, and, most important of all, sugar. On a smaller geographic scale, they carried foods from town to town and country to country, spreading localized food traditions within Europe and creating regional cuisines.

The flow of Jews from southern Europe (most were from Italy, where Jews had been living since the days of the Roman Empire) continued through the twelfth century. By this time, a distinct Jewish culture had evolved in the Rhineland and taken root, but only temporarily. The ever-shifting political environment kept the Jews moving. The period of the Crusades, which began at the end of the eleventh century and lasted for another two hundred years, was a particularly difficult period for the Ashkenazim. On their way to the holy land, crusading soldiers, in a fit of religious zeal, would stop to torture Jews, in some cases wiping out entire towns.

Jewish hatred stirred up by the Crusades set the tone for the next several centuries. State-sponsored expulsions, massacres, and anti-Jewish riots pushed the Jews farther east and north into Poland, Lithuania, and beyond. At the same time, more subtle forms of persecution prevented Jews from staying too long in any one place. Within German-speaking Europe, locally enforced laws restricting the Jews’ right to own property, to work in certain occupations, to live where they chose, and even when they could marry left the Jews both rootless and poor. Many worked as itinerant peddlers, traveling by foot and selling assorted dry goods, pots and pans, needles, thread, and fabric. The truly destitute lived as wandering beggars. For the most part, the Jewish migrations flowed eastward, but if the political situation in Poland or Russia became too inhospitable, Jews circled back into Germany.

The history of Ashkenazi cooking tells the story of a people in motion. Since they came from Italy, it shouldn’t surprise us that many early dishes show a strong Italian influence. The most obvious is pasta, or noodles, which the Jews called

vermslich

, or

grimslich

, words derived from the Italian “vermicelli.” In one medieval noodle dish, a favorite among twelfth-century rabbis, the dough was cut into strips, baked, and drizzled with honey, an early ancestor of noodle kugel. Boiled noodles arrived in Germany roughly three centuries later, another food carried north, this time by traders, many of whom were Jews. In his book

Eat and Be Satisfied

, John Cooper describes a dish called

pastide

, an enormous meat pie of Italian origin, typically filled with organ meats. Too large to finish in a single sitting, the pie was baked in its own edible storage container: a thick whole-grain crust that was chipped away at each successive meal. Like noodles,

pastide

was generally eaten on Friday evenings, a Sabbath tradition that lasted through the eighteenth century.

4