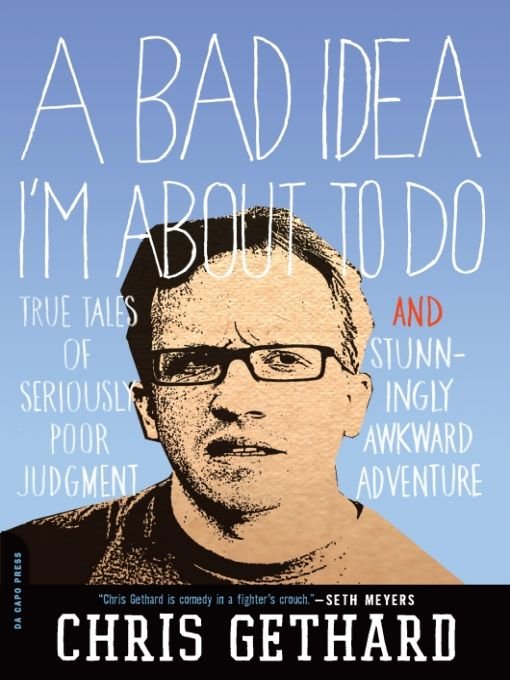

A Bad Idea I'm About to Do

Read A Bad Idea I'm About to Do Online

Authors: Chris Gethard

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

What Others Are Saying About Chris Gethard and

A Bad Idea I'm About to Do

A Bad Idea I'm About to Do

“Chris Gethard is comedy in a fighter's crouch. His stories travel through adolescence and New Jersey with a sweetness and rage that makes you both wish you were there and feel like you were.”

âSeth Meyers,

Saturday Night Live

Saturday Night Live

“Whenever I'm feeling down on myself or think that I'm slowly going crazy, I think of one of Gethard's stories. Then I realize that, hey, I don't got it so bad after all.”

âJack McBrayer,

30 Rock

30 Rock

“Chris Gethard tells the amazing stories an eccentric old man would tell . . . if that man had lived his fucking life with any balls. His stories are hilarious and rivetingâbut more importantly, real.”

âRob Huebel, Adult Swim's

Childrens Hospital

and MTV's

Human Giant

Childrens Hospital

and MTV's

Human Giant

“Chris Gethard stories are like a roller coasterâat times you are scared, shocked, and ultimately exhilarated by the hilarity each story containsâand once you finish one, you wanna hear another one right away.”

âPaul Scheer, FX's

The League

and Adult Swim's

NTSF: SD: SUV

The League

and Adult Swim's

NTSF: SD: SUV

“Chris Gethard is one of my favorite storytellers. He's amazing! He's always getting into the most unusual situations.... Even normal situations become amazing when you're Chris Gethard. Seriously, when Geth is talking, I stop and listen.”

âRob Riggle,

The Daily Show with Jon Stewart

The Daily Show with Jon Stewart

“Maybe you shouldn't tell me things like that.”

âChris's mom responding to the distressing news that her son might have herpes

To my mother and my Aunt Re,

who while sitting at my kitchen table and

talking into the night taught me that sad stories

stop being sad if you can make them funny.

who while sitting at my kitchen table and

talking into the night taught me that sad stories

stop being sad if you can make them funny.

Introduction

“W

ould you like to hear a story I've never told anyone?” my mother asked.

ould you like to hear a story I've never told anyone?” my mother asked.

We were in the living room of my parents' home in New Jersey. My mother sat in her familiar spot on the couch. My dad was at the kitchen table.

It was Mother's Day 2010.

Foolishly, I said “Sure.”

“Great,” she began. “It's about your birth.”

My father interrupted as he entered from the other room. “And I've never heard it?”

“No,” she said. She paused, looked at me, and continued. “I've never had the heart to tell anyone this story.”

That's the moment it first hit me that when your mother asks you if you want to hear a story no one's ever heard, you should probably always say “No.”

“When you were little and the other kids used to make fun of how big your head was,” she told me, “it always broke my heart.”

This meant her heart was broken nearly every single day. My forehead has always been an obtrusive, disproportioned source of embarrassment to me. My childhood nickname was “Megahead.” (In many ways this was a good thing. While “Megahead” made me angry, I preferred it to being mocked about how my last name phonetically spells out the words “Get Hard.”)

“I knew since day one that was going to be a problem for you,” she continued. “Because when you were being born and you started crowningâyou know, emerging? The doctor took a step back and said, âMy God, his head is as big as a bowling ball.' ”

I froze.

That's how my life began

, I thought to myself.

That's literally the first thing that ever happened to me. It wouldn't even be fair to measure my life in units of time yet. I was only three

inches

old and I was being mocked by the medical care professional whose job it was to bring me into life safely

.

, I thought to myself.

That's literally the first thing that ever happened to me. It wouldn't even be fair to measure my life in units of time yet. I was only three

inches

old and I was being mocked by the medical care professional whose job it was to bring me into life safely

.

My mom had obviously thought I would laugh at this story. When she saw that instead I was reeling from it, she tried to make a joke to recover.

“Well,” she sighed, “you'll never know how many stitches they gave me.”

Her joke didn't make me feel any better.

“How many?” I asked. I was approaching full panic.

She got very serious as she realized she was digging herself into a deeper hole.

“No, seriously, you'll never know,” she said. “They refused to tell me.”

That pushed me over the edge. “Jesus, I'm sorry!” I spat out.

I have to say, apologizing to your mother on Mother's Day for being born is not one of life's peaks. That can safely be described as a valley.

Before I could say anything, my father jumped in with his own attempt at a joke meant to save the situation.

“Actually,” he said, “you should be apologizing to

me

for that.”

me

for that.”

That's how I spent last Mother's Day.

T

hat story verifies a suspicion I've long heldâthat my life has always been semi-ridiculous. Having lived the kind of life I've lived, I wasn't surprised at all to find out that's apparently been the case literally from the start. It figures that even my birth would be weird.

hat story verifies a suspicion I've long heldâthat my life has always been semi-ridiculous. Having lived the kind of life I've lived, I wasn't surprised at all to find out that's apparently been the case literally from the start. It figures that even my birth would be weird.

On paper, I appear to have it made. Everything about my upbringing seems to subscribe to the good old American dream. Raised in the suburbs, parents still married, good gradesâif anyone should have had it easy, boring, and normal, it's me.

But right from the start I was perceptive enough to recognize that the traditional idea of a “normal life” doesn't really exist. There are cracks in its armor that anyone can see from a mile away. For example, the seemingly idyllic suburb I was raised in was actually filled with maniacal weirdos. My unfractured family in fact put on stunning displays of rage and lunacy. From a very early age, I'd see and experience things that would make me think

This isn't right

and

I have a feeling life is in general more messed up than anyone is letting on

. This type of thinking bred into me an unfortunate blend of curiosity and defiance.

This isn't right

and

I have a feeling life is in general more messed up than anyone is letting on

. This type of thinking bred into me an unfortunate blend of curiosity and defiance.

What I've come to realize is that most people, when faced with a situation that seems ludicrous or dangerous, instinctually take action to avoid it. I, on the other hand, have always wanted to charge headlong into outlandish situations at first sight of them. The weirder something is, the more I want to know about it. The less likely it is for a guy like me to be a part of something,

the more I want to get involved. My philosophy has always been “Why say no to anything?” The only things you have to abandon in order to live by it are common sense, a command of reason, and social acceptability. Not a bad trade.

the more I want to get involved. My philosophy has always been “Why say no to anything?” The only things you have to abandon in order to live by it are common sense, a command of reason, and social acceptability. Not a bad trade.

In the early part of this book, you'll see what I mean about the foundation that my early life laid out for me. I'd wager that if you had the same male role models I did, you wouldn't quite know how life is supposed to work, either. By the time I describe my adventures as a young adult, you'll have learned how I'd developed a personality that got me into car chases, prison (voluntarily), and many other ill-advised pursuits. Then you'll see how things only snowballed from there.

Sometimes when I tell people these stories, I get the feeling they think I'm crazy. Over the years, I've come to realize that they're probably at least a little bit right.

But to me, it always seemed that everything and everyone

around

me was crazy, and that not embracing or addressing that realization would actually make me the weird one. Pretending everything was okay all the time, when life is so odd and often so harsh, seemed more damaging than not.

around

me was crazy, and that not embracing or addressing that realization would actually make me the weird one. Pretending everything was okay all the time, when life is so odd and often so harsh, seemed more damaging than not.

As a result, I've made a lot of foolish decisions. Many people hear about the stuff I've pulled and call me an angry person. The stories you are about to read will definitely reflect that. Others have called me depressed, and I am unable to argue with that diagnosis. Still others have viewed me as standoffish or socially awkward. I'm probably guilty on all counts.

But I don't think any of those individual labels hit the nail on the head. To me, they're mere extensions of what I really am and always have beenâconfused.

Just terribly, terribly confused. About why things work the way they do and why we all pretend that things aren't weird in one way or another

almost all the time

.

almost all the time

.

Unless, of course, it's just me.

But, listen, I'm working on this impulse of mine to dive into the middle of situations both awkward and strange.

Less than two weeks ago, I took the R train from my neighborhood in Queens into Manhattan. It was early afternoon on a Wednesday. At first, everything about the experience was perfectly average.

As I sat in the largely empty subway car, I had my face buried in my BlackBerry, because lately I've been addicted to playing poker on it. This activity helps pass the time, and also helps me maintain the social norm of public transportation in New York City, which is to never make eye contact with anyone, ever.

“EXCUSE ME LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, I NEED A MOMENT OF YOUR TIME,” I heard from the other end of the car. This is not an unusual sentence to hear on a New York City subway. But the aggression and volume put into this particular delivery caused me to look up wide-eyed.

At the other end of the car, the homeless guy responsible for the disruption prepared to launch into his spiel. He didn't look particularly crazy by the standards of New York City homeless people. But he soon proved that looks can be deceiving.

Apparently, I was not the only person to react to him with surprise.

“Oh, this cunt doesn't have the time for me!” the homeless gentleman continued. “Bitch gonna roll her eyes at me.”

“Cunt” is one of the few words that can slice through the thickest of skin. At the very least, it makes any situation more awkward than it was before. I was born and raised in New Jersey, where profanity is considered a quaint regional dialect. Now I live in New York City, where just days ago I witnessed two women going for the same taxi.

Other books

The Ancient Curse by Valerio Massimo Manfredi

Relentless by Adair, Cherry

The Elephant Whisperer: My Life With the Herd in the African Wild by Lawrence Anthony, Graham Spence

Summoned and Stolen (Summoned Series Romances) by Hayes, Susan

Sir Francis Walsingham by Derek Wilson

When Honey Got Married by Kimberly Lang, Anna Cleary, Kelly Hunter, Ally Blake

The Diary of Darcy J. Rhone by Giffin, Emily

In Search of Mary by Bee Rowlatt

Dream Unchained by Kate Douglas

Masterpiece (The Masters of The Order Book 1) by Verne, Jillian