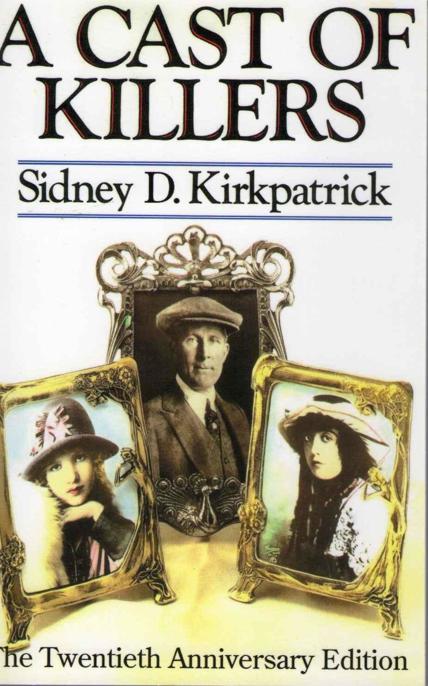

A Cast of Killers

Authors: Sidney Kirkpatrick

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Actors & Entertainers, #Artists; Architects & Photographers

A CAST OF KILLERS

BY SIDNEY D. KIRKPATRICK

The Twentieth Anniversary Edition

A Cast of Killers

The Twentieth Anniversary Edition

Copyright 2007 by Sidney D. Kirkpatrick

All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from Sidney D. Kirkpatrick, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

First Published in the United States by E.P. Dutton, a division of New American Library, 2 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016.

This edition published by Sidney D. Kirkpatrick

1 Birch Lane, Stony Brook, N.Y. 11790

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Data

Kirkpatrick, Sidney

A cast of killers

1. Murder-California-Los Angeles-Case studies

2. Taylor, William Desmond, 1877-1922.

3. Murder-California-Los Angeles-Investigation-Case studies.

4. Vidor, King, 1885-1982. I. Title.

HV6534.L7K57 1986 364.I’523’0979493 85-31202

ISBN 0-525-24390-9

A CAST OF KILLERS

BY SIDNEY D. KIRKPATRICK

Also by Sidney D. Kirkpatrick

Turning The Tide: One Man Against The Medellin Cartel

Lords of Sipan: A True Story of Pre-Inca Tombs, Archaeology, And Crime

Edgar Cayce, An American Prophet

The Revenge of Thomas Eakins

Hitler’s Holy Relics

This edition is dedicated to Colleen Moore

I returned to the William Desmond Taylor murder case in much the same way as I would return to an old bottle of wine I’d put away. When I searched out the bottle recently and brushed some of the crusted dust off it, I realized it was vintage stuff—the rarest vintage of all: a murder that has never been solved. One opens such a bottle at his own peril.

KING VIDOR,

1967

PREFACE

King Vidor was a biographer’s dream—he saved everything. In assembling information for an authorized biography of the late Hollywood director, I found boxes, file cabinets, entire closets filled with 1925 press clippings, laundry receipts from 1934, valentines dated 1956. Even the smallest detail of his everyday life could be chronicled. But I discovered an intriguing gap in the story these things told. There were no important papers for the year 1967. It was as if the director, or a close personal friend, had picked the estate clean of items for that year.

I asked Vidor’s friends and family about this unaccounted-for year. They told me the director had been working on a secret project in 1967, but no one knew what it was. He had traveled extensively, carrying a thick black binder in which he took notes. On one occasion, he called a friend from the Directors Guild and asked him if he wanted to hunt for a bullet lodged in the closet of a downtown mansion. To a second friend, he suggested a trip to Ireland, to do genealogical research.

Nearly a year later, after I had thoroughly cataloged Vidor’s estate, 1967 still remained a mystery. The only clues I had to work with were his tax returns and phone bills. He had indeed been working on something and had written off a considerable amount of money for travel and research. He had called police departments as near as Sacramento, California, and as far as Scotland Yard. My curiosity piqued, I put off writing and focused exclusively on finding out what the director had been doing. When all else failed, I instituted a search of Vidor’s three homes, prying up floor boards in attics, hunting in basement crawl spaces.

Twenty-three days into my search, I knelt beside the hot-water heater in the garage of Vidor’s Beverly Hills guest house and uncovered a locked black strongbox. A tire iron on the wall a few feet away cracked the padlock. A black binder sitting inside, and stacks of loose notes and documents, told me I had found exactly what I was looking for.

I studied the contents of that black strongbox with a deep sense of foreboding, as if this were a prelude to a much longer quest. At first I was intrigued, then shocked. The black strongbox told of the director’s briefly turning away from filmmaking to solve the scandalous murder of a friend and fellow film director, William Desmond Taylor. The results of Vidor’s investigation were sensational and explosive. So why had Vidor salted them away?

As I set out to answer that question, I began writing a new book: the story of King Vidor solving the murder of William Desmond Taylor. It wouldn’t be the story I had set out to write, but I knew it would be the story Vidor wanted told. To him, a film director was only as important as the story he had to tell. And what a story this was!

The resulting book is as accurate and factual an account as I believe possible. All of the events, episodes, and persons portrayed are real. All living participants were interviewed, and only original documents and source material consulted. Dialogue was reconstructed based on Vidor’s notes and the recollections of witnesses.

King Vidor, I had come to learn, had sealed away the contents of the strongbox until such time as the story they told could be made public without injuring the reputations or careers of living participants. The time has now come that the story can be told.

SIDNEY D. KIRKPATRICK

Willow Creek Ranch Paso Robles, California, January 1986

404 Alvarado Street on the night of February 1, 1922

Illustration Brian Borden

1

King Vidor rose early. While his wife slept, he showered, shaved, ate a small breakfast, and began his working day. As he stepped outside on Monday morning, December 5, 1966, the sun rising over the eucalyptus trees in his yard promised the kind of southern California day that film directors pray for. But Vidor wasn’t shooting a picture that day. He had another, more important project at hand: solving a murder.

In dark sunglasses and his favorite brown-checkered cap, he drove his supercharged red Thunderbird down Sunset Boulevard and out of Beverly Hills. Having once dreamed of becoming a race car driver, he loved taking full advantage of the T-Bird’s power and maneuverability as he crisscrossed through the side streets of Hollywood and Hancock Park on his way downtown.

When he reached Westlake, the residential slum bordering the business district, he couldn’t help remembering the neighborhood’s glorious past. Once, not many years earlier, stately homes had sat among palm and citrus trees; now all that remained were seedy boarding houses, unattended billboards, and the abandoned trolley tracks, barely visible through the latest layer of asphalt.

Vidor parked beside a Mexican food stand at the top of Alvarado Street. He bought coffee, then made his way down to number 404, on the east side of the street.

The address was a construction site, a pile of rubble waiting for the dumpster. Workers scurried about on foot

and machines, while haggard onlookers watched.

Sidestepping potholes, Vidor took a seat at a bus stop, wondering if any of the others around him had also read the Los Angeles

Times

article about the bungalow court being demolished, or if they were merely passing time, attracted to any activity in the dying neighborhood.

He noticed a deeply tanned man with large, tattooed arms, kicking through the rubble. The man looked up at Vidor, then away. Vidor sipped his coffee and thought back nearly forty-five years, to the time when 404 Alvarado Street, now just another victim of urban decay, had been the setting for one of the greatest scandals in Hollywood history.

On the morning of February 2, 1922, a team of Los Angeles Police Department investigators met at that same Alvarado Street address. The cool morning air still held the acrid odor of the smudge pots that nearby orange growers burned at night to warm their groves. As the investigators entered Bungalow B, to investigate a simple case of natural death, they encountered a flurry of unexpected and quite peculiar activity. Accounts of what they found were as varied as the sources that reported them, but there could be no doubt that the intrigue taking place had the drama of a first-class detective story.

In the most sensational accounts of what had transpired, two important executives of Famous Players Lasky, the film production arm of Paramount Pictures, were said to be burning papers in Taylor’s fireplace, while Mabel Normand, the film comedienne in line to inherit—in light of her friend Fatty Arbuckle’s recent imprisonment on manslaughter charges stemming from the alleged rape and murder of a young girl at a wild sex party—the title of Hollywood’s biggest comedy star, was rifling through drawers in search of something. Henry Peavey, black houseman to the bungalow’s occupant, was busy in the kitchen, while all around the house individuals not readily identified milled about (one walked out the front door with a case of bootleg liquor and never returned). During all of this commotion, on the floor of the study, William Desmond Taylor, one of the most important film directors in Hollywood, lay dead.

The investigators found Taylor on his back, his arms at his side. His face was composed and his clothes meticulously arranged, as though he had calmly lain down to sleep. An overturned chair had fallen across one of his legs. One investigator found a monogrammed handkerchief on the floor beside the body. He picked it up and placed it on Taylor’s cluttered desk.

As the investigators asked everyone in the bungalow to stop whatever they were doing, a middle-aged man made his way through the crowd of reporters and photographers gathering outside. He entered the front door and identified himself as a physician visiting a patient in the neighborhood. He asked if he could be of any assistance and was led to the study, where he quickly examined Taylor’s body and said the director had died of a stomach hemorrhage brought on by natural causes.

Mabel Normand and the studio executives told the investigators that Taylor had often suffered terrible stomach cramps, that he had in fact had to travel to Europe a few months before to visit specialists about his condition. Henry Peavey, long a trusted employee of Taylor’s, concurred, saying that only the night before, Taylor had asked him to get him some medication on the way to work the next morning. He showed them the bottle of milk of magnesia, still wrapped in the brown paper from the druggist down the street.

The investigators pieced together what had obviously happened: Taylor had hemorrhaged, fallen from the chair he had been sitting in, and died. They asked everyone in the bungalow just what he or she was doing there. Mabel Normand said she had come to retrieve letters and telegrams she had written to Taylor. They had nothing to do with his death, she said; she just wanted to keep them private. She said Taylor kept them in the middle drawer of his bedroom dresser. But when investigators looked in the drawer, it was completely empty.

Others in the bungalow claimed to be after similar personal items, but like Mabel Normand’s letters, none of those items was alleged to have been found.

Investigators were puzzled by this air of mystery surrounding an otherwise routine case. But then, as people had long liked to suspect, and as the Fatty Arbuckle scandal confirmed for them, a lot more went on within the motion picture community than was ever made public.

Then, less than an hour after the official investigation into the death of William Desmond Taylor was closed, it was reopened, with a completely new emphasis. After questioning everyone in Taylor’s bungalow and sending them on their way, the investigators watched as Taylor’s body was placed on a stretcher to be removed to the funeral home. On the floor where the body had been was a small, dark pool of blood. Investigators turned the body over and found a neat bullet hole in his back.

Anyone could see that Taylor had been murdered. Why then had the man claiming to be a physician declared death by natural causes? The investigators would never know for the man was never seen again, nor was he ever identified. The monogrammed handkerchief that had been found by the body also disappeared forever.

Taylor’s neighbors were immediately questioned.

Douglas MacLean, a noted actor and friend of Taylor’s who lived across the courtyard, said he had heard what might have been a muffled shot the night before, sometime between 8:00 and 8:15. His wife, Faith Cole MacLean, had looked out the window and seen a man wearing a cap and muffler leaving Taylor’s front door. She described the man as about five feet, ten inches tall, of medium build, and roughly but not shabbily dressed. Upon later questioning, Mrs. MacLean said she couldn’t be certain it had been a man she had seen; it might have been a woman dressed as a man. Hazel Gillon, another neighbor, was even less sure. All she said she had seen was a dark figure.