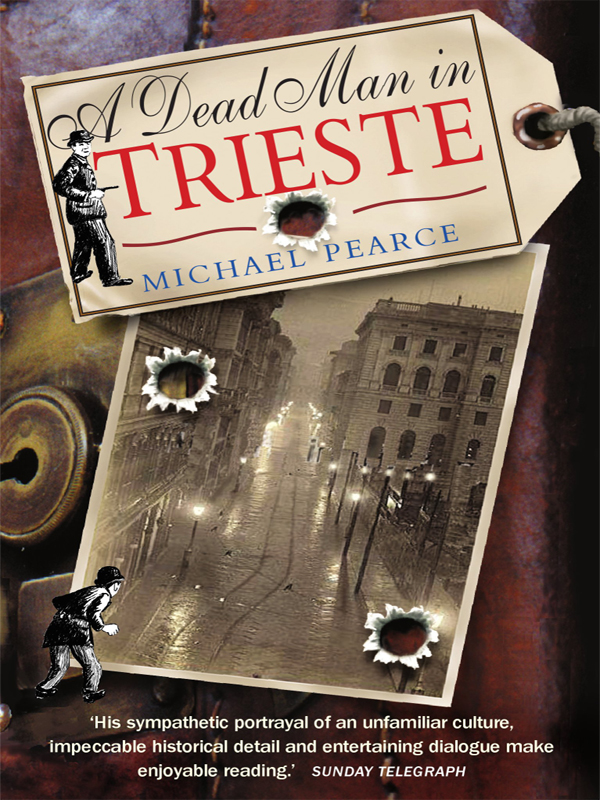

A Dead Man in Trieste

Read A Dead Man in Trieste Online

Authors: Michael Pearce

A Dead Man in Trieste

A DEAD MAN

IN TRIESTE

Michael Pearce

First published in Great Britain 2004

by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters, 162 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

Copyright © 2004 Michael Pearce

The right of Michael Pearce to be identified

as the author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988

ISBN 1–84119–667–3

Printed and bound in Great Britain

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

Contents

Trieste was, so they had told him, the tinderbox of Europe: the sort of place where, at any moment, a spark might ignite the whole powder keg. And they were nearly right, only the spark came almost four years later, in 1914, and it wasn’t in Trieste but just round the corner, in Sarajevo, when the assassination of the Archduke set in motion the train of events which became the First World War. Might, if things had been different, the killing of Lomax have been that spark, Seymour asked himself later? Only that was after the powder keg had exploded, and he was asking himself among the hailstorm of shells and bullets that was the Battle of the Somme, when he wasn’t really in a condition to think clearly about anything.

On that earlier day, in Trieste, as he sat, newly arrived from London, in one of the cafés on the great central piazza, outside in the sun, all that was not just far away but totally unimaginable, so far beyond the reach of normal experience that you just, somehow, couldn’t even think it.

What, actually, he was thinking, as he sat there sweating, still in the hot, dark suit, quite inappropriate for the Mediterranean but which, as a poor policeman from the East End of London, was the only one he had, was that this was all right.

Only three days before he had been in the grime of the East End; except that you hadn’t been able to see the grime, in fact, you hadn’t been able to see anything, because there had been a real old peasouper of a fog, come up from the docks along with a seawater chill which had driven him indoors and kept him stoking the coals of the police station fire. That was where he had been when his instructions came.

And now here he was, under the great blue sweep of the Mediterranean sky, basking in the sun, looking out through the trees at the end of the piazza at the liners in the bay.

‘Very nice!’ the Inspector had said when he had finished giving him his instructions. ‘Sunshine. Palm trees. A holiday trip,’ he had said enviously.

‘Trieste?’ said Seymour. ‘Where’s that?’

The Inspector had held back at this point, but eventually – ’Italy?’ he hazarded.

This, although he had not known it, was fighting talk in Trieste. At the time, though, Seymour had felt relieved.

‘That’s all right,’ he had said. ‘I can manage Italian.’

‘Ye-es?’ said the Inspector, who had always thought there was something funny about Seymour.

Before going along to the Foreign Office to be more properly informed of his responsibilities, Seymour had taken the trouble to look Trieste up in the atlas. It was about half-way along the coast between what Seymour thought of as the top of Italy and –

Well, the Balkans. A lot of little countries, Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Herzegovina, who all got along like a house on fire. Actually,

exactly

like a house on fire.

Trieste, however, belonged to none of these. It was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which at that time covered most of the southern half of Central Europe, reaching down to the sea at only one point: Trieste. Through Trieste much of its trade passed. The port was therefore important to the Empire; too important to let go. On the map the Empire hung poised above tiny Trieste like a great bulk about to fall. And that was pretty much how it seemed to Trieste’s extraordinary diversity of inhabitants.

For that was the other thing about Trieste. Within its small confines there were Italians and Austrians and Greeks and Serbs and Croats, Montenegrins and Maltese, Slovenians and Slovakians, Bosnians and Herzegovinians, not to mention Germans and Spanish and French. It was the point at which many different peoples met, met and rubbed together. And where they met there was friction, and where they rubbed there was always the possibility of a spark. Trieste was Europe in miniature, a place where all its peoples were pressed uncomfortably together, like gunpowder pressed into a barrel, like gunpowder awaiting a spark.

Through the trees on the westward side of the square he could see ships. There was a pier just beyond the trees with a ship tied up alongside it. He could see the name of the line. It was written twice, in German and in Italian:

Osterreicher

Lloyd

, and

Lloyd Austriaco

. He had noticed that before, on his walk down from the hotel. Everything seemed to be double here.

In the café most of the people were speaking Italian. He listened idly to the conversation, trying to get used to the language again.

But this was embarrassing. He had thought he had known Italian, told them that he had. That was why they had picked him. But this was different from the Italian he knew. Odd phrases crept in from other languages: German, he could understand that, Slovenian, he could make a shot at. But ‘

sonababic

’? It took him some time to work out that it was English: son of a bitch. The influence of the docks, he supposed.

Seymour knew about docks. He had been born and bred not far from London’s docks in the East End, had worked almost all his life, even when he had moved to the Special Branch, in London’s dockland. It was where immigrant families like his tended to settle when they first came ashore. Even when they moved, later, they didn’t move far. They tended to stay in the East End even if they weren’t working in the docks. They stayed with what they knew.

They came ashore in waves, the Jews at one time, the Poles, like his grandfather, at another. There had been others since. When you walked around the East End or went into its pubs and bars you would hear all kinds of languages. It was, although he did not know it, not so very different from Trieste.

It was a world, he thought, that, though foreign, the Foreign Office did not know. Lomax would not have known it. Maybe he would have known about it more than those people Seymour had met in the Foreign Office in London, because he was a consul and his work in Trieste would have taken him down if not into the docks, at least into the port. But he wouldn’t really have known because, from what Seymour had seen, Foreign Office people lived in a world apart.

When he had gone in he had found two people sitting behind a desk, an older man and a younger one. The older one had looked at him without warmth.

‘You know what this is all about, I suppose?’ he said, as if he doubted it. ‘Rather different, I imagine, from anything you’ve been used to.’

He turned to the younger man.

‘In fact, so different that I really wonder – do we have to?’ he asked.

‘Proceed? I’m afraid so. The Minister was particularly insistent.’

‘Yes, but – a policeman!’

‘They’re the ones who usually handle this sort of thing.’

‘Yes, I know, but that’s in the ordinary way. Surely this is a bit different?’

‘That is, of course, why we asked for someone from the Special Branch.’

‘Yes, but . . . You’ve never dealt with anything like this before, have you?’ He turned the papers in front of him. ‘Whitechapel. Is that where you have been working? Your . . .’ He seemed to pick up the word with tongs and look at it. ‘. . . beat?’

‘Not “beat”, exactly. In the Special Branch. But it’s where I’ve been working. The East End generally.’

‘The East End?’ It was spoken almost with incredulity. He looked at the younger man. ‘About as far, I imagine, as you can get from . . . well, the world he would be investigating.’

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ said the younger man. ‘Trieste, the docks.’

‘You know what I mean. Our world. The world of the Foreign Office. Paris, Vienna.’

‘This is just a consul.’

‘It’s still our world, though, isn’t it? And a very different one from the one this gentleman is acquainted with. He’ll be like a fish out of water. I don’t know why they sent him.’

‘Languages,’ said the younger man. ‘We stipulated languages.’

‘But has he got them? What languages, in fact,’ – the scepticism was evident – ‘do you have?’

‘French, German, Italian, Hungarian, Polish –’

‘But to what level?’ the man broke in. ‘A few words are all very well down in . . . Whitechapel’ – he spoke the word as if it was somehow unclean – ‘but you’ll need rather more if –’

‘Actually, the level of foreign languages expertise in Whitechapel is rather high,’ said Seymour, stung. ‘They’re all native speakers.’

The younger man laughed.

‘Immigrants, you mean?’ said the older man.

‘Yes.’

‘Hmm.’ He was silent for a moment, considering. Then he said: ‘And you yourself?’

‘My grandfather was Polish, my mother Hungarian.’

The older man looked at the younger man again.

‘Is that all right?’

‘Very helpful, I would have thought.’

‘No, I don’t mean the languages.’

‘When did your family come over here?’ asked the younger man.

‘My grandfather came in the early fifties.’

‘After the Year of Revolutions?’ said the younger man, amused.

‘That’s right.’

‘With the police after him?’ said the older man.

‘The Czarist police, yes.’

‘He was a revolutionary?’

‘I think in English terms he would have counted just as a liberal. Today he votes Conservative.’

‘And your father?’

‘Born here. As I was.’

‘Does he share your grandfather’s views?’

‘Which ones? The old ones?’

The man made an impatient gesture with his hand.

‘He runs the family business. It’s a timber business down by the docks. He doesn’t have much time for politics. Take that in any sense you wish.’

The younger man laughed. The older one looked at him with irritation.

‘This is important,’ he said.

‘It’s also sixty years ago,’ said the younger man.

‘I know, I know. But one has to be sure. The point is,’ he said to Seymour, ‘this is an investigation which has to be handled with extreme sensitivity. Diplomatic sensitivity. There are currents . . . One would need to be confident that the man we send out was not going to be drawn into them . . .’

‘Unlike, perhaps, the person whose death he would be investigating,’ murmured the younger man.

Lomax, the British Consul at Trieste, had disappeared. That much seemed to be certain, although much else wasn’t. The younger man, for instance, had said he was dead.

Dead?

‘It seems the most likely thing,’ said the younger man, ‘in the circumstances.’

‘Could you tell me about the circumstances?’

‘The immediate ones are that he was in the main piazza with some friends.’

‘Drinking,’ said the older man.

‘And then?’

‘He left. And hasn’t been seen since.’

Seymour waited, but it looked as if nothing was going to be added.

‘Is that all?’

‘All?’ said the older man. ‘Isn’t that enough?’

‘No body?’

‘Body!’

‘Not yet,’ said the younger man.

‘Or anything that suggests foul play? Apart from his having disappeared?’

‘This is Trieste,’ said the younger man softly.

‘But mightn’t he have just, well, gone somewhere?’

‘If you go somewhere, you usually come back,’ said the younger man.

‘Is it possible that he could simply have walked out?’

‘Walked out?’

‘On the job.’

‘Consuls do not walk out on their job,’ said the older man severely. ‘At least, British ones don’t.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Seymour doggedly, ‘but I still don’t see why you should presume that he is dead.’

The younger man and the older man looked at each other. The older man sighed impatiently.

‘It’s the kind of man he was,’ said the younger man.

‘Always getting himself involved,’ said the older man. ‘Quite improper! For a consul.’

‘And what we know of the situation out there.’

‘Involved in what? What

is

the situation out there?’

The younger man hesitated.

‘Hadn’t that better wait until you get out there? It will all make much more sense to you then.’

‘I doubt it,’ said the older man.

‘Oh, I think Mr Seymour will soon get a feel for things.’

‘A tinderbox,’ said the older man. ‘An absolute tinderbox. And that’s what we’re sending him out into. One fool after another!’

But nothing seemed less like a tinderbox, as he sat there in the sun, looking at the sea sparkling through the trees, and watching the seagulls swoop in to pick up the crumbs beneath the tables. That morning, after he had checked in at his hotel, he had gone first to the Consulate and then to the main police station. In the police station he had been taken to see a Mr Kornbluth, who, it appeared, was the officer in charge of the case.

Kornbluth was sitting behind his desk, big, heavy, stolid, unyielding, like a great block of masonry, or, perhaps, a pile of rubble. He looked at Seymour unblinkingly. He seemed to be working something out. Then he said, haltingly, in English:

‘You wished to see me?’

Seymour, going by the name, replied helpfully in German.

‘I am from the British Consulate,’ he said. ‘My government’ – that was a good start. He would soon get the hang of this diplomatic business – ‘is anxious to know the circumstances in which the Consul disappeared.’

He waited.

Kornbluth said nothing.

‘I wonder if you could tell me something?’

For a moment it appeared that Kornbluth could not, but then, almost reluctantly, he said:

‘He was reported missing on Wednesday, the 23rd.’

‘And?’ prompted Seymour, when it seemed that Korn-bluth was going to stop there.

‘At 10.45 a.m.’

Was he merely obtuse? Or was he doing this deliberately? A word, a German word, rose up in Seymour’s mind:

lumpen

. That’s what Kornbluth was:

lumpen

.

‘Could you give me some more details, please?’

‘The last time he was seen was the evening before. In the Piazza Grande. He was with a bunch of layabouts.’

‘Layabouts?’

‘His friends.’ Kornbluth’s voice was heavy with disapproval.

Seymour was slightly taken aback. Layabouts? He would have to look into this.

‘Always he was with them.’

‘The layabouts?’

‘In the piazza. Drinking.’ Kornbluth shook his head. ‘For a consul, it was not seemly.’

‘Well, no. And that’s what he was doing that evening?’

‘As every evening.’

Seymour was beginning to get the picture.

‘And then he left?’

‘

Si

.’

‘At about what time?’

‘Nine thirty. Or so they say.’

He had slipped, apparently unconsciously, into Italian. Seymour followed him.

‘Have they any idea where he might have been going?’

‘They think he might have had an appointment. He kept looking at his watch.’

Now that he was speaking Italian, he seemed to talk more freely.

‘I have looked in his appointments book, however, and there is no mention of any appointment there. His clerk, Koskash, knows nothing about one. I have spoken to the port officials – there could have been a boat coming in. But there wasn’t. At the port they know nothing about it. Nor in the offices, nor in the banks.’

He paused.

‘There is, anyway, something wrong in all this.’

‘Something wrong?’

‘Appointment? Business? Evening?’ Kornbluth shook his head and suddenly appeared to twinkle. ‘In Trieste,’ he said, ‘no one does any business in the evening!’

He glanced at his watch.

‘Nor at lunchtime,’ he said. ‘How about an aperitif?’

Now that he was speaking Italian he seemed a different man.

‘I’m sorry I spoke in German,’ Seymour said. ‘I was going by the name.’

‘It

is

German,’ Kornbluth said. ‘Or, rather, Austrian. But that was a long time ago. My family have been here for, well, over a hundred years. Trieste born and bred, that’s what I am.’

‘And so you grew up speaking Italian?’

‘Not Italian,’ corrected Kornbluth. ‘Triestino.’

‘Ah!’ said Seymour. ‘That’s it! I’d been wondering why it was different.’

‘And the difference is important,’ said Kornbluth. He looked at Seymour curiously. ‘You can hear it? You speak Italian very well.’

‘But not Triestino,’ said Seymour.

Kornbluth clapped him on the shoulder.

‘Not yet,’ he said. ‘But after a slivowicz or two, you will.’ He held the door open. ‘We’ll go down to the old city,’ he said, ‘and I’ll tell you something about Trieste. And about Signor Lomax.’

The Canal Grande ran back from the bay in a long three-hundred-yard spur right into the heart of the city. At the end was a domed church with a classical portico. Between the Ionic columns girls were sitting darning socks and cutting out material for cloaks. Both sides of the canal were lined with working sailing boats from which singleted crewmen were unloading sacks on to the quay. Occasionally the sacks were torn and Seymour could see what they contained: olives, pistachio nuts, figs, muscatel raisins. Whenever the contents spilled out on to the quay they were immediately seized on by young girls who scooped them up and put them in the pocket made by lifting up the front of their dress.

As well as sacks, there were barrels, either of wine or of olive oil. There were also barrels, not sacks, of coffee beans. Seymour had seen the barrels standing outside shops. Sometimes they were open and then the pungent smell spread out across the street.

The harbour was framed by tall neo-classical buildings which rose up on each side. Kornbluth took him to a little café at the foot of one of these where the tables spread out across the quay right to the edge of the water. From where they sat they could look down into a boat piled high with watermelons. The men had stopped half-way through unloading and on the quay above was a similar stack. The ripe, almost over-ripe, smell of the melons hung over the tables.

Kornbluth looked around him with satisfaction.

‘Do you know what I see here?’ he said.

‘Boats?’ hazarded Seymour.

‘Work!’ said Kornbluth. ‘The work that has made Trieste what it is. I like to see people working. I don’t mean shoving bits of paper around. I mean really putting your back into it. Now you don’t always see that down in the new docks where the large ships are. It’s all cranes and things. But you do see it here. And what I like about it is that it’s real. Real people handling real things, olives and nuts and so forth. Watermelons,’ he said, looking down into the boat. ‘Not fancy people pushing bits of paper around. Ah, I know that’s progress, that’s what it’s got to be when you’re a big port, as Trieste is these days, the seventh busiest in the world, so they say. But it all started here, right here, in what was the old port, with people working their asses off.’

He sipped his slivowicz.

‘And that’s what I don’t like about layabouts. Sitting there drinking what other people’s sweat has earned.

‘Sweat was what built Trieste. That, and one other thing: order. Oh, I know what you think: he’s a bloody policeman and so he goes on about order. But just think what Trieste is. It’s Austrians and Albanians and Italians and Croats and Slovenians – Slovenia is only five miles away, you know – and Greeks and Turks and Montenegrins and Christ knows what. Now, how are all these buggers going to live together and work together if you don’t have order? They’d be at each other’s throats in half a minute.

‘So, order and sweat. That’s made Trieste what is it. Now I love Trieste and I like it as it is. And I don’t want to see it go. But go it would if some of these bastards with their half-baked ideas had their way.’

‘Go?’ said Seymour.

‘That’s what they want. Some of them.’

‘Go? How can it go?’

’Like Venice. Venice was part of the Austrian Empire fifty years ago. And now it’s part of Italy.’

‘Well, Venice

is

part of Italy. Look at the geography.’

‘So is Trieste, in some people’s view of geography. The geography of those layabouts, for instance.’

‘The ones Lomax was with?’

‘That’s right. What I’ve got against them is not just that they’re layabouts but that they want to take my city from me.’

He looked at Seymour.

‘And that’s the sort of people your Consul spent his time with,’ he said. ‘The sort of people he had for his friends!’

After they had parted, Seymour walked slowly back to the Consulate. It was getting towards noon and the heat lay heavily on the streets. Shops were closing for lunch and siesta and even when they were open there didn’t seem many signs of activity. A few latecomers were still pushing through the bead curtains of the doors of the bread shops but the windows were empty. Most of the day’s baking had gone. In some of the dark side streets there were sounds from the tavernas but for the most part the city had gone quiet.

When he got to the Consulate he half expected to find it closed but the clerk, Koskash, was still inside, a bread roll and an orange on the desk beside him. No, he said, he didn’t go home for lunch; and he wouldn’t have done that anyway, in the circumstances and knowing that Seymour was here.

He was a thin, grey-haired, anxious-looking man. When Seymour had gone in that morning he had got to his feet and bowed in the Continental fashion. There was an air of formal, old-fashioned politeness about him. Like almost everyone Seymour had met, he seemed to speak several languages, switching easily from Italian to English to German. Going by his name, his home language was none of these.

It had been a distressing, sad time, he said. He and Signor Lomax had worked closely together. He had developed a great esteem for the Signor, had always found him very

simpatico

. It had been a great shock when –

Signor Seymour would find everything in order, though. There was, truthfully, not a lot of business coming into the office at the moment and what there was was all routine. He, Koskash, could handle it. Indeed, he normally did handle it. Signor Lomax left most things to him, concentrating on the occasional necessary negotiations that were the usual feature of a port consul’s job. He would drop in at the Consulate every morning to see how things were going and to check on what had to be done, but after that would go on down to the piazza.

Down to the piazza? Well, that was where he liked to spend the day. He was, the clerk explained, very much an ‘al fresco’ consul.

Fresh air consul? What was that?

The clerk hesitated.

Well, it was just that he liked to spend the day there. Usually in the Caffé degli Specchi, the Café of Mirrors. Always in the same place, at the same table.

With the same people?

Was it imagination or did Koskash shift uneasily?

Usually with the same people, yes. The artists.

Artists?

Signor Lomax was interested in art. Surely Signor Seymour had noticed the paintings in his room?

Signor Seymour had not, but he went to take a look now. How had he missed them when Koskash had shown him into the room that morning? The walls were a blaze of colour. On second thoughts he could see how he had missed them. He had looked away. They were such a blaze of colour that they quite hurt the eye. Unfortunately, there didn’t seem to be much else. They weren’t of anything and there didn’t seem to be any pattern or shape to them.

‘In Trieste,’ said Koskash diffidently, ‘there are many artists. There is something new here, they say. In the world of art. But I’m afraid I don’t really know . . .’

And nor, certainly, did Seymour. There wasn’t much call for art in the East End. Artists, there were occasionally, taking advantage of the cheap housing, but somehow he had never seen their pictures. He wouldn’t have known what to make of them if he had. He felt uncomfortable with art, as he did with anything that required you to show your feelings. In Seymour’s hard, tight little world of the police and the docks feeling was something you kept quiet about.

On a small table set back against one of the walls was a pile of scrap metal. There were cogs, bearings, a kind of collar and a small shaft. It could have been a boat engine stripped down. But, no, Seymour was no engineer but even he could see that the bits didn’t fit together. It was just a pile of scrap. Strange place to put it. Or – wait a minute – was it . . .? Could it, too, he wondered uneasily, be Art?

He closed the door and returned to the main office. One thing was already becoming clear: Lomax was a bit of an odd bloke.