Read A Death in Belmont Online

Authors: Sebastian Junger

A Death in Belmont (13 page)

It was thought that whoever was doing the killing probably had some prior history of misbehavior, but that opened up an enormous investigatory task. There were thousands of men in the Boston area who had crossed some line with the female sex, and they all had to be tracked down and evaluated as suspects. A disturbed young man from Belmont was picked up after nurses at a hospital caught him trying to look into the ladies' room. He quickly confessed to killing Beverly Samans in May 1963, but he got his facts sufficiently mixed up that the police had to release him. A married woman called in her suspicions about a man who lived in her apartment building, but it turned out she'd been having an affair with him and was enraged when he called it off. An extremely violent psychotic who had attacked two elderly women in the towns of Salem and Peabody was questioned in the strangling death of an elderly woman named Evelyn Corbin, but the only physical evidence linking him to the crime was a half-eaten doughnut on Corbin's fire escape. The man had eaten doughnuts for breakfast that day, but that wasn't enough evidence to bring charges. A paranoid schizophrenic who washed dishes in a restaurant a block from Mary Sullivan's apartment was also questioned and released, and a black man who knew Sophie Clarkâand had a secret life as a homosexualâwas given a lie detector test and released despite the fact that he had flunked it badly. Detectives had extremely good reason to suspect some of these men, but they could not arrest them without a confession or strong physical evidence. A doughnut on a fire escape or a failed lie detector test was not, in and of itself, proof that someone had committed a crime.

W

HILE BOSTON WAS

trying to track down a serial killer, America was slowly emerging from its fog of grief. The murder of the president, as it turned out, was not just a low point in an otherwise upward-trending time for the country; it was the lip of a long slide into turmoil. Early in 1964 Congress passed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which authorized President Johnson to use “all necessary measures” to protect U.S. forces abroad. Within months Johnson had ordered air strikes against North Vietnamese forces in response to attacks against the American base in Pleiku. At home racial issues were coming closer to dividing the country than anytime since the Civil War. Dr. Martin Luther King's nonviolent tactics started to gain adherence among black activists, but an ex-convict named Malcolm X dismissed them out of hand. “If you think I'll bleed nonviolently, you'll be sticking me for the rest of my life,” Malcolm X said. “But if I tell you I'll fight back, there'll be less blood. I'm for reciprocal bleeding.”

Malcolm X went on to promise that 1964 would be the “hottest

summer in history,” and it came close. In June, King was jailed in St. Augustine, Florida, for trying to eat at a segregated lunch counter. A few weeks later three civil rights workers in Mississippi were killed by a deputy sheriff and a part-time Baptist minister and buried in an earth levee near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Then, in July, riots ignited in Harlem after a New York City police officer shot and killed a fifteen-year-old black boy who was carrying a knife. An angry mob surrounded the precinct house after word of the killing got out, and the police chief had to call for reinforcements to keep from getting overrun. Gunfire was so heavy up Lenox Avenue that night that reporters said it sounded as if police were shooting automatic weapons. The violence sputtered on for days.

Northern reporters went down to the Mississippi Delta to cover the civil rights movement as if they were going to Vietnam to cover the war, not knowing whether they'd make it back. One photographer who had gotten chased by a carload of white thugs found it necessary to buy at 12-gauge shotgun and continue his reporting with the gun across his lap. Meanwhile enlightened ideas about race seemed to be making some headway in the upper echelons of government. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, which gave the federal government broad powers to combat racism at the state level. In November 1964, Lyndon Johnson used that issue to win the presidential election against Barry Goldwater, who, despite the fact that he was half Jewish, was utterly opposed to the antidiscrimination measures in Congress.

In early 1965, an article in

Look

magazine quoted Malcolm X as saying that the debate between violence and nonviolence was, in reality, a debate between self-defense and masochism. In late February, Malcolm X was gunned down in a Harlem ballroom by three young black men who were then nearly beaten to death by the

crowd. Two weeks later, riot police in Selma, Alabama, decimated a peaceful protest march with tear gas and nightsticks under orders from Governor George Wallace, who vehemently opposed black voter registration and new federal antisegregation measures. The attack backfired, not only bringing Dr. King to Selma, but promoting a speech by President Johnson before Congress that was interrupted thirty-six times by applause. Johnson told Congress that the country had waited more than a hundred years for true freedom and that the time for waiting was gone. “There is no Negro problem, there is no Southern problem, there is no Northern problem,” he declared. “There is only an American problem. There's really no part of America where the promise of equality has been fully kept.”

The date was March 15, 1965. Television cameras showed some congressmen moved nearly to tears and others slumped in their seats like recalcitrant schoolboys. Johnson blew kisses to his wife as he finished his speech and strode out of the chamber. A new era in America had begun.

Â

IT WAS SOMETIME

in early Marchâbetween the Selma riots and Johnson's historic speechâthat the phone rang in our house, and when my mother answered it, she was surprised to hear Russ Blomerth on the line. Russ hadn't called in two yearsânot since the studio had been finishedâbut he had odd and urgent news. Mrs. Junger, he told her, I don't know how to tell you this. But I've just found out that Al DeSalvo is the Boston Strangler.

There was only one telephone in our house, a white rotary desk phone that sat on a shelf by the entrance to the kitchen, and next to the shelf there was a small stool. My mother felt her knees go out from under her, and the next thing she knew, she was sitting on the

stool. She had never told Russ about the incident with Al in the basementâshe'd never even told my fatherâbut now it all came back to her.

He was just caught on a rape case, Blomerth went on. And then he confessed to being the Boston Strangler.

Blomerth presumably wanted my mother to hear the news from him before she read it in the newspaper. DeSalvo had begun making lengthy confessions to the police, and Blomerth had already been contacted by investigators to provide corroborating evidence. DeSalvo, as it turned out, had been alone or off the clock for every single strangling in the Boston area. The authorities were particularly interested in December 5 and December 30, 1962, which were the days Sophie Clark and Patricia Bissette had been killed. Blomerth said his records showed that on those days, Al had come to our house by himself to check on the diesel heaters. “The exact hours that he did this I have no way of knowing,” Blomerth testified in writing. “But I must tell you that Albert was a truly remarkable man. He had unbelievable strength, energy and endurance. He was completely lovable to every individual while working for me. Never was there any deviation from the highest proper sense of things.”

So Al had left our house and gone on to kill a young woman. Or he had killed a young woman and then showed up to work twenty minutes later; either possibility was too horrifying to contemplate. Al had spent many, many days working in the studio while my mother was home alone; all he'd had to do was ask to use the bathroom or the telephone, and he was inside the house with her. It would be stupid to kill someone you were working forâyou'd be an immediate suspect, like Roy Smithâbut couldn't you do it on a day when no one knew you were there? Al came to our house to check the heaters unannounced and on no particular schedule. What

would have prevented him from attacking my mother and then slipping away afterward?

My mother hung up the phone and shuffled through her memories of DeSalvo. What about the afternoon when Bessie Goldberg was killed; could Al have driven over to Scott Roadâwhich he passed every day on his commute from his home in Maldenâand killed her and then gone back to work? My mother had come home that day to a phone call from my baby-sitter telling her to lock the doors because the Boston Strangler had just killed someone nearby. She had hung up the phone and gone in back to repeat the bad news to Al, who was painting trim on a stepladder. What could have possibly been going through Al's mind during that conversation? If he was indeed the Strangler but hadn't killed Bessie Goldberg, it must have been a terrific shock to hear about a similar crime so close by. And if he

had

killed Bessie Goldberg, there my mother stood at the foot of the ladder telling him about it. How would my motherâalone in the house with dusk falling and a dead woman down the roadâhave appeared to the man who had just committed the murder?

Four months earlier Al had stood at the bottom of the cellar stairs and called up to my mother with an odd look in his eyes. For a moment, at least, our basement was a place where the very worst things imaginable could happen without anyone around to prevent them. Was there some equivalent place in Al's mind where he went in those momentsâsome dark cellar hole filled with dead women and a staircase leading back up into the rest of his life? If so, why had he not gone down there, figuratively speaking, while my mother stood in the studio talking about the latest murder? What had protected her from the fate that those other women had suffered?

There was no way to know; my mother just remembered Al

saying how terrible it was about the Goldberg murder and then going back to painting trim. By seven o'clock that night, my father had returned from work and was hearing from my mother what had happened on Scott Road that day. Dr. Edwin Hill of the Harvard University Department of Legal Medicine was snapping on his latex gloves at the Short and Williamson Funeral Home and commencing the autopsy on Bessie Goldberg's body. Al was already at home with his wife and children. Roy Smith was drinking cheap whiskey in a Central Square apartment and either worrying about the fact that he'd just committed murder orâif he hadn'tâworrying about how he was going to convince the police of that.

And Leah and Israel Goldberg, still deeply in shock, were answering endless questions at 14 Scott Road. They had not yet started out across a continent of grief that a lifetime of walking could not cover.

A

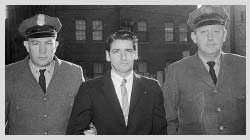

LBERT DESALVO

, Bridgewater Correctional Institution:

“That day of the first one, it was in summer of 1962 and I think it was raining or going to rain because I remember I had a raincoat with me. I told my wife I was going fishing and I took my rod and a fishing net that had these lead weights in it, I must have known I was going to do it because I had the lead weight in my pocket when I went into her building. I don't know why I went there, I was just driving around feeling the thing build up, the image, and when it got strong so I just couldn't stand it, then I'd just park and go into the first place coming along like it was just right for me to go in there. I went into number 77, I remember it said that on glass over the door in gold letters, and that the door was heavy but it was open and I just walked in. I went up to the top floor and she let me in without no trouble. Most of them was scared at first but I talk good and act like I don't care whether they let me in or not. I talk fast and I ain't sure what I'm saying sometimes, you know? Inside her apartment to the left was a kitchen then, down a

little hall maybe ten feet, the bathroom. The light was on. I see a sewing machine. It was brown. A window with drapes, a light tan bedroom set, a couch, a record player, tan with darker colored knobs. The bathroom is yellow, the tub would be white and she was going to take a bath because there was water in it. Music is playing, long-hair symphonies and stuff like that, after I turned it off but I ain't sure if I got it all the way off. She took me along to show me the bathroom, what had to be done there for work, turning her back on me. When I see the back of her head I hit her on the head with the lead weight. She fell. I put my arm around her neck, and we fell together on the floor. She bleed a lot, terrible. After I put the belt around her neck I ripped open her robe and I played with her and pulled her legs apart, like this. I think she was still alive when I had intercourse with her. Then I look around and I'm angry, I don't know why and I don't really know what I'm looking for, you understand me? After, I took off my jacket and shirt and washed up and made a bundle. I grabbed her raincoat out of the brown cabinet in the bedroom. I went out wearing her raincoat, a tan one, carrying my shirt and jacket wrapped in my own raincoat. The first thing I see when I come out of the apartment is a cop. He looks at me but I don't pay no attention and go right past him to my car. I got into my car and drove around until I came to an army and navy store and I took off her raincoat and left it in the car and went into the store and bought a white shirt and put it on in the store. I drove towards Lynn and cut up my shirt and jacket with my fishing knife and threw them into a marsh where I know the waves will come and wash them away. Then I went home.”