A Durable Peace (45 page)

Authors: Benjamin Netanyahu

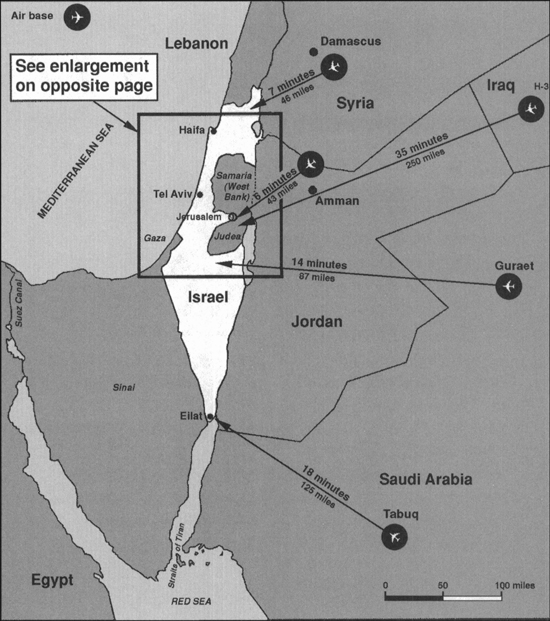

9. Israel’s Strategic Vulnerability 1949–1967

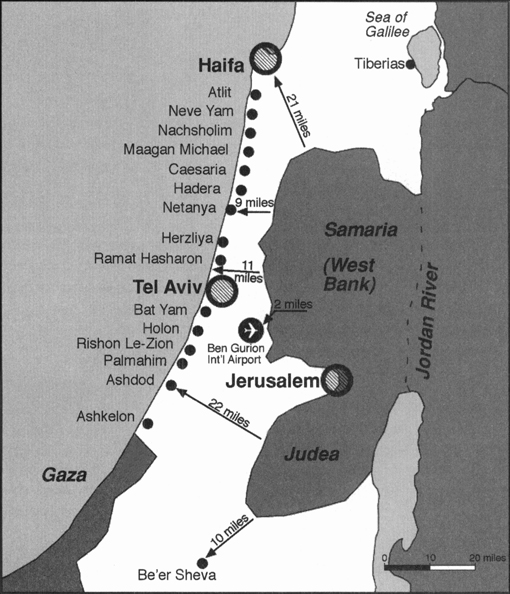

10. Israel’s Exposed Shoreline 1949–1967

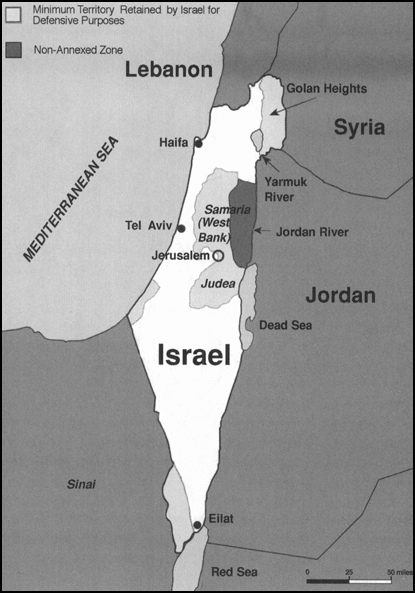

11. The Pentagon Plan for Israel’s Security Needs June 18, 1967

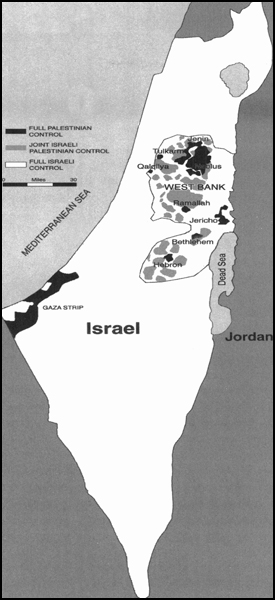

12.1999 Israel After the Oslo Accords

[Without the territories, a] dwarfed Israel would then be an irresistible target for Arab adventurism and terrorism, and ultimately

for an all-out military assault which could end Israel’s existence….

If Israel were to relinquish the West Bank… it would have virtually no warning of attack…. Virtually all the population would

be subject to artillery bombardment. The Sharon Plain north of Tel Aviv could be riven by an armored salient within hours.

The quick mobilization of its civilian army… would be disrupted easily and perhaps irreversibly.

9

The view of the generals was forcefully elaborated upon in November 1991 by Lieutenant-General Thomas Kelly, who had served

as the director of operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the Gulf War and who visited Israel later that year:

It is impossible to defend Jerusalem unless you hold that high ground…. [I] look onto the West Bank and say to myself, “If

I’m chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces, I cannot defend this land without that terrain.”… I don’t know about politics,

but if you want me to defend this country, and you want me to defend Jerusalem, I’ve got to hold that ground.

10

Of course, the position of successive administrations in Washington has not been based on such cold strategic calculations.

The U.S. government cannot escape the intense politicization of the issue that has taken place since 1967, and the version

of Israel’s defense needs to which the United States is officially committed is skewed accordingly. This is why a great many

American officials insist on ignoring their generals and asserting that an Israel ten miles wide can count portions of the

Mediterranean in its tally of the strategic depth available for its defense, evidently believing

that the Israeli army can walk on water. But there is a limit to the number of miracles an army can perform, and Israel’s

soldiers have performed more than most. No country should ask its army to continue to do the impossible, especially since

it would be hard pressed to perform even the ordinary military tasks that security dictated while standing on the head of

a pin.

This is obvious enough even to nonmilitary observers who have become acquainted with Israel’s geography. Their common sense

tells them what every military planner knows: Never prepare for the previous war. But here Israel is being asked to prepare

to fight the Six Day War again, a conflict that preceded the previous war by several wars—except that the conditions that

prevailed before June 5, 1967, and that allowed Israel to escape death then are gone forever. For one thing, a repetition

of the surprise Israeli air strike that demolished all the Arab air forces in 1967 is impossible, because since 1968 Arab

military aircraft no longer sit on open runways but are sheltered underground in fortified bunkers. For another, after 1969

the Arabs acquired highly effective antiaircraft missiles, which took a deadly toll of Israel’s air force in 1973. And with

the improvement of Arab battle strategy, the long hesitation that allowed Israel the time to mobilize its troops, which was

the fatal error of the Arab coalition on the eve of the Six Day War, will certainly not occur again. Further, the Arab armies

have increased three- and four-fold in size. Their slow-moving infantry divisions of the past have become rapidly moving armored

and mechanized formations. Arab artillery is no longer towed but is self-propelled.

But whereas the Arabs have plenty of space to deploy their massive armies around Israel’s borders, a truncated Israel would

find it extremely difficult to field its army, which has also been enlarged since 1967, in the small stretch of space between

the edges of Tel Aviv’s suburbs and the border. It is therefore absurd to assume that since Israel survived a previous attack

from the boundaries of the Six Day War, it could necessarily do so again.

One way I have tried to get this point across to foreign visitors

is by flying with them from Sdeh Dov, the small airport on the Tel Aviv beach, to the pre-1967 border a few miles to the east.

The helicopter traverses the suburbs of Tel Aviv and reaches the last house of the last suburb, Kfar Saba, in minutes. From

there it flies over a small field, then reaches the Arab town of Kalkilya across the old border. Before the 1967 war, the

distance between Kfar Saba and Kalkilya used to be a number of miles. But Kfar Saba has grown, and so has Kalkilya. “That,”

I say, pointing to the few hundred yards that currently separate the last house in Kfar Saba from the first house in Kalkilya,

“is what most of the world intends to be Israel’s strategic depth.”

Beyond Kalkilya, we can see the wall rise up: the mountains of Samaria, which from the air look like a castle fortress looming

up over the coast. Then I ask the pilot to fly due west to the coast, heading directly for embassy row on Tel Aviv’s beachfront

Hayarkon Street. If the visitor is American, the pilot flies us over the American embassy; if British, over the British embassy,

and so on. The round trip takes all often minutes. When the visitor is a diplomat from a country that is particularly dogmatic

about having Israel “return the West Bank,” he can easily imagine himself working in an embassy all of five minutes’ helicopter

flight from the new border that his government insists Israel should have.

On one occasion I was explaining the significance of this tiny distance to an American senator. The pilot became very excited

and joined in on my side of the discussion. It turned out that he was the brother of a prominent civil servant who was identified

with Israel’s dovish Labor party.

“Tell him who you vote for,” I said to the pilot, guessing.

“Labor,” he answered. “But what’s the difference? We all want to live.”

While this determination never to return to the pre-1967 borders is shared by most Israelis, a small minority has emerged

that does not have the same qualms about withdrawing to these lines. Since this minority exercises considerable influence

in Israel’s media

and politics (it is very potent in the left), its argument should be paid due attention. To counter the menacing geographic

reality, the members of this school of thought argue that in the age of missiles the amount of territory Israel holds does

not matter. For if the Arabs possess projectiles that can fly over a territorial defense and hit Israel’s cities and military

bases, what use is territory? This simple formulation has great appeal and is receiving much currency. After all, wasn’t Israel

attacked by Iraqi Scud missiles fired from a thousand miles way? What difference does it make whether it controls or does

not control the West Bank?

However appealing, this argument is based on a fallacy Missiles do not win wars. They can do damage, even terrible damage,

but they do not conquer territory. The intense bombing of North Vietnam by the United States caused considerable destruction,

but since the American army did not invade North Vietnam and take possession of its territory, the United States could not

win the war. Similarly, the devastating American air strikes against Saddam’s troops in Kuwait and Iraq, with everything from

smart bombs to cruise missiles, could not by themselves win the war. Ground action remained indispensable to physically drive

Iraq’s army from Kuwait. Israel might be attacked from the air, but it cannot be overrun and conquered without being physically

overrun and physically conquered. And this can be done only by armies possessing tanks, mobile artillery, and mechanized infantry

that can move into a territory and take possession of it. The distance they have to cover and the terrain they must negotiate

at the start of the fighting are vital factors in determining the outcome of battles. Distance may not make much difference

to missiles, but to an armored division it makes a world of difference whether it must cover 12 miles or 120 miles to reach

its target, and whether the ground it must cross is flat or mountainous. (In point of fact, larger distances do diminish the

effectiveness of missiles as well, though in a different way The same Scud missiles that were fired at Israel from distant

Iraq are now in the possession of nearby Syria, which would be able to pack twice the explosive payload

into each warhead because of the shorter distance the missile must travel to reach its target.)

The physical barrier that the West Bank places before incoming divisions is of particular value in the age of missiles. Israel

must mobilize the bulk of its army to ward off a threat, but in the age of missiles we must assume that the time needed for

such mobilization will

increase.

For missiles, even unsophisticated ones like the Iraqi Scuds, can hit population centers with ease, thereby disrupting the

flow of Israeli civilians to their mobilization centers. As one Israeli reserve officer told me, “If missiles rain down on

my city, I’ll rush to my daughter’s school to see if she’s alive before I head for my unit.” And as the missiles get more

deadly and more accurate, they can be pinpointed on the mobilization bases themselves and on the road intersections that lead

to them, thus further delaying the deployment of Israeli troops toward the front. If, during such an aerial bombardment, enemy

ground troops were to advance toward Israel’s borders, Israel would be hard pressed to bring the reserves to the front to

oppose them. Initial terrain conditions would therefore be even more vital for Israel’s small standing army as it seeks to

hold off the assault of the far larger Arab forces until the arrival of reinforcements. Israel would need more rather than

less space to absorb an attack and buy for itself the precious time it needed to regroup. Thus, the protective wall of the

West Bank provides invaluable time and space.

The age of missiles has introduced not only long-range missiles but also short-range missiles. For these weapons, too, territory

is a vital consideration. I am referring to such weapons as SAM-7s and shoulder-fired American Stinger missiles that can down

helicopters and fighter aircraft with devastating effectiveness. Just how effectively they can do this had been seen in the

war in Afghanistan by the mid-1980s. The mujahideen had been all but crushed by the Soviet army and air force when the United

States decided to supply them with Stingers. This was the turning point of the war. A few years later, Soviet air power in

Afghanistan was almost obliterated by peasants firing sophisticated missiles

from mountaintops. Israel has recently had to contend with thousands of youngsters throwing stones on the hills of Samaria.

Imagine the situation if those youngsters were replaced by thousands of PLO fighters carrying not rocks but rockets, which

could shoot down Israeli military and civilian aircraft. Israel’s international airport, after all, is two miles from the

West Bank, and all except one of the Jewish state’s military airfields are within range of various short-range missiles that

could be easily placed on the West Bank, crippling Israel’s military precisely as the mujahideen crippled the Soviet military.

Of course, such weapons were not available to the Arabs when they controlled the West Bank twenty-five years ago. Today courtesy

of years of Soviet supplies, they are a key component of their arsenals. And there is a growing fear in the West that the

deadly Stingers that were supplied to the Afghanis, Kuwaitis, and others have been making their way into the hands of terrorists—such

as the PLO.