A History of the Crusades-Vol 3 (20 page)

In May 1216 Pope Innocent went to Perugia

to try to settle the long feud between Genoa and Pisa, that both might

contribute to the transport of the Crusaders. There, after a short illness, he

died on 16 July. Few Papal reigns have been more splendid or more outwardly

triumphant. Yet his dearest ambition, to recover Jerusalem, was never realized.

Two days after his death the aged Cardinal Savelli was elected Pope, as

Honorius III.

1217: The Crusaders’ Delay

Honorius eagerly took over his great

predecessor’s programme. A few days after his accession he wrote to King John

at Acre to tell him that the Crusade was coming. John was growing anxious; for

his truce with al-Adil was due to expire next year. Honorius also wrote round

to the Kings of Europe. Few of them responded. In the far north King Ingi II of

Norway took the Cross, only to die next spring; and when the Scandinavian

expedition started out it was a paltry affair. King Andrew II of Hungary had

already taken the Cross, but had been excused by Innocent from fulfilling his

vow earlier because of civil war in his country. He now showed zeal, but he had

another motive. His Queen was the niece, through her mother, of the Latin

Emperor Henry of Constantinople, who was childless, and he had hopes of the

inheritance. But when Henry died in June 1216, her father, Peter of Courtenay,

was chosen in his place. King Andrew’s ardour began to fade; but he agreed at

last to have his army ready by the following summer. In the lower Rhineland

there was a good response to the preaching; and the Pope hoped for a large

fleet manned by Frisians. But here again there were delays. Nor was the news

from Palestine very encouraging. James of Vitry, who had recently been sent

there as Bishop of Acre, with instructions to rouse the local Latins, gave a

bitter report of what he found. The native Christians hated the Latins and

would prefer Moslem rule, while the Latins themselves led indolent, luxurious

and immoral lives and were completely Oriental. Their clergy was corrupt,

avaricious and intriguing. Only the Military Orders were worthy of

commendation, though the Italian colonists, who were wise enough to lead frugal

lives, kept some energy and enterprise; but the mutual jealousy of the great

Italian cities, Venice, Genoa and Pisa, made them unable ever to work together.

In fact, as Bishop James discovered, the Franks of Outremer had no desire for a

Crusade. Two decades of peace had added to their material prosperity. Since

Saladin’s death the Moslems showed no tendency to aggression, for they too were

profiting by the increased commerce. Merchandise from the interior filled the

quays of Acre and Tyre. The palace that John of Ibelin had built at Beirut bore

witness to revived prosperity. There were Italian colonies happily established

in Egypt. With the purchasing power of Western Europe steadily growing, there

was a fine future for the Mediterranean trade. But it all depended precariously

on the maintenance of peace.

Pope Honorius thought otherwise. He hoped

that a great expedition would be sailing from Sicily in the summer of 1217. But

when the summer came, though various companies of French knights had reached

the Italian ports, there were no ships. The King of Hungary’s army reached

Spalato in Dalmatia in August, and was joined there by Duke Leopold VI of

Austria and his army. The Frisian fleet only reached Portugal in July, and part

of it remained at Lisbon. It was in October that the rest sailed in to Gaeta,

too late to proceed to Palestine till the winter was over. At the end of July

the Pope ordered the Crusaders assembled in Italy and Sicily to proceed to

Cyprus; but still no transport was provided. At last in early September Duke

Leopold found a ship at Spalato to take his small company to Acre. His voyage

took only sixteen days. King Andrew followed him about a fortnight later; but

the Spalatans could not let him have more than two ships; so the bulk of his

army was left behind. About the same time King Hugh of Cyprus landed at Acre

with the troops that he could raise.

The harvest had been poor that year in

Syria, and it was difficult to feed an idle army. When the Kings arrived, John

of Brienne recommended an immediate campaign. On Friday, 3 November, the

Crusaders set out from Acre and marched up the plain of Esdraelon. Their

numbers, though not great, were larger than any that had been seen in Palestine

since the Third Crusade. Al-Adil, when he heard that the Christians were

assembling, had come with some troops to Palestine, but he had not expected so

early an invasion. He was outnumbered; so, when the Crusade advanced towards

Beisan, he retired, sending his son al-Mu’azzam to cover Jerusalem, while he

waited at Ajlun, ready to intercept any attack on Damascus. His fears were

scarcely justified. The Christian army lacked discipline. King John considered

himself as being in command, but the Austro-Hungarian troops looked only to

King Andrew and the Cypriots to King Hugh, while the Military Orders obeyed

their own leaders. Beisan was occupied and sacked. Then the Christians wandered

aimlessly across the Jordan and up the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee,

round past Capernaum and back through Galilee to Acre. Their chief occupation

had been the capture of relics. King Andrew was delighted to obtain one of the

water-jugs used at the marriage feast at Cana.

King John was dissatisfied and planned an

expedition of his own to destroy the fort that the Moslems had erected on Mount

Thabor. Neither Hugh nor Andrew joined him, nor would he wait for the Military

Orders. His first attack on the fort, on 3 December, failed, though in fact the

garrison was ready to surrender. When the Orders arrived two days later a

second assault was attempted, but in vain. Once more the army retreated to Acre.

1218: King Andrew returns Home

About the New Year a small band of

Hungarians, against local advice and without their King’s approval, planned a

foray into the Bekaa and was almost annihilated in a snowstorm when crossing

the Lebanon. Meanwhile King Andrew rode off with King Hugh to Tripoli, where

Bohemond IV, ex-Prince of Antioch, recently widowed of his first wife,

Plaisance of Jebail, celebrated his marriage to Hugh’s half-sister, Melisende.

There Hugh suddenly died, on 10 January, leaving the throne of Cyprus to an

eight-month-old boy, Henry, under the regency of his widow, Alice of Jerusalem.

King Andrew returned to Acre and announced his departure for Europe. He had

fulfilled his vow. He had recently added to his relic-collection the head of St

Stephen. It was time to go home. The Patriarch of Jerusalem pleaded with him

and threatened him in vain. He took his troops northward, through Tripoli and

Antioch, to Armenia, and thence, with a safe-conduct from the Seldjuk Sultan,

to Constantinople. His Crusade had achieved nothing.

Leopold of Austria remained behind. He was

short of money and had to borrow 50,000 besants from Guy Embriaco of Jebail,

but he was ready to work further for the Cross. King John used his help for the

refortification of Caesarea, while the Templars and Teutonic knights set about

the construction of a great castle at Athlit, just south of Carmel, the Castle

of the Pilgrims. Al-Adil meanwhile dismantled his fort on Mount Thabor. It was

too vulnerable and not worth its upkeep.

On 26 April 1218 the first half of the

Frisian fleet arrived at Acre, and a fortnight later the half that had wintered

at Lisbon. There was news that the French Crusaders massed in Italy were soon

to follow. King John at once took counsel about the best use to be made of the

newcomers. It had never been forgotten that King Richard had advised an attack

on Egypt; and the Lateran Council had also mentioned Egypt as the chief objective

for a Crusade. If the Moslems could be driven out of the Nile valley, not only

would they lose their richest province, but they would be unable to keep a

fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean; nor could they hold Jerusalem long against

a pincer attack coming from Acre and from Suez. With the Frisian ships at their

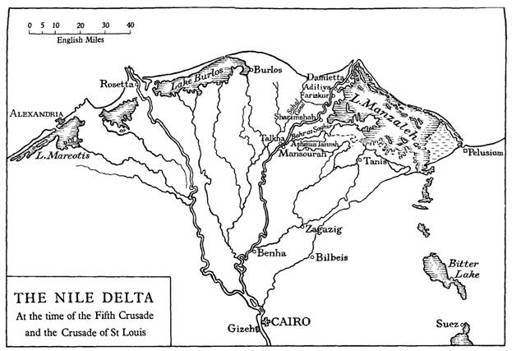

disposal the Crusaders now had the means for a great attack on the Delta.

Without hesitation it was decided that the first objective should be the port

of Damietta, the key to the Nile.

1218: The Crusade lands in Egypt

The Sultan al-Adil was an old man now and

had hoped to spend his latter years in peace. He had his worries in the north.

His nephew, az-Zahir of Aleppo, died in 1216, leaving as his successor a child

called al-Aziz, for whom a eunuch, Toghril, acted as regent. Az-Zahir’s

brother, Saladin’s eldest son, al-Afdal, emerged from his retirement at

Samosata to make a bid for the inheritance and summoned to his help the Seldjuk

Sultan of Konya, Kaikhaus. The Anatolian Seldjuks were now at the height of

their power. Byzantium was no more; and the Emperor of Nicaea was too busy

fighting the Franks to disturb them. The Danishmends had faded out. Their

Turcoman subjects were settled now and orderly, and prosperity was returning to

the peninsula. Early in 1218 Kaikhaus and al-Afdal swept into the territory of

Aleppo and advanced on the capital. The Regent Toghril, knowing al-Adil to be

threatened by the Crusade, appealed to his young master’s cousin, al-Ashraf of

Iraq, al-Adil’s third son. Al-Ashraf routed the Seldjuk army near Buza’a;

al-Afdal retired back to Samosata; and the Prince of Aleppo had to acknowledge

al-Ashraf as his overlord. But the Seldjuks remained a menace until the death

of Kaikhaus next year, when he was planning to intervene in a disputed

succession at Mosul. This enabled al-Ashraf to consolidate his power, and to

become a serious rival to his brothers further south.

Up to the last al-Adil seems to have hoped

that the Franks would not be so foolish as to break the peace. His son,

al-Malik al-Kamil, viceroy of Egypt, shared his hopes. Al-Kamil was on

excellent terms with the Venetians, with whom he had signed a commercial treaty

in 1208. In 1215 there were no fewer than 3000 European merchants in Egypt. The

sudden arrival that year at Alexandria of two Western lords with an armed

company had frightened the authorities, who had put the whole European colony

under temporary arrest. But good relations had been restored. In 1217 a new

Venetian embassy was cordially received by the viceroy. The ineffectual

meanderings of the Crusade of 1217 had not impressed the Moslems. They could

not believe that there was any danger now.

On Ascension Day, 24 May 1218, the

Crusading army, with King John in command, embarked at Acre in the Frisian

ships, and sailed down to Athlit to pick up further supplies. After a few hours

the ships lifted anchor, but the wind dropped. Only a few of them managed to

leave the anchorage and sail on to Egypt. They arrived off the Damietta mouth

of the Nile on the 27th, and anchored there to await their comrades. The

soldiers did not venture at first to try to land, as there was no senior

officer amongst them. But on the 29th, when still no fleet appeared, the

Archbishop of Nicosia, Eustorgius, persuaded them to accept Count Simon II of

Sarrebruck as their leader and to force a landing on the west bank of the river

mouth. There was very little opposition; and the operation was nearly complete

when the sails of the main Crusader fleet appeared over the horizon. Soon the

ships came in across the bar and King John, the Duke of Austria and the Grand

Masters of the three Military Orders stepped ashore.

Damietta lay two miles up the river, on

the east bank, with its rear protected by Lake Manzaleh. As the Franks’

experience in 1169 had shown, it could not be efficiently attacked except by

water as well as by land. As in 1169 a chain had been stretched across the

river a little below the town, from the east bank to a tower on an island close

to the west bank, blocking the only navigable channel; and a bridge of boats

lay behind the chain. The Crusaders made this tower their first objective.

When the Moslems realized that the Crusade

was directed against Egypt, al-Adil hastily recruited an army in Syria, while

al-Kamil marched the main Egyptian army northward from Cairo and encamped at

al-Adiliya, a few miles south of Damietta. But he had insufficient men and

ships to attack the Christian positions, though he reinforced the tower. The

first serious assault on the fort, at the end of June, failed. Oliver of

Paderborn, the future historian of the campaign, then suggested the making of a

new device, for which he and one of his fellow-citizens paid. It was a tower

built on two ships that were lashed together, covered with leather and fitted

with scaling-ladders. The fort could now be attacked from the river as well as

from the shore.

On Friday, 17 August, the Christian army

held a solemn service of intercession. A week later, on the afternoon of the

24th, the assault began. About twenty-four hours later, after a fierce

struggle, the Crusaders managed to establish themselves on the ramparts and

poured into the fort. The garrison fought on till only a hundred survivors

remained; then it surrendered. The booty found in the fort was immense, and the

victors made a small bridge of boats to carry it to the west bank. They then

hacked down the chain and bridge of boats across the main channel, and their

ships could sail through, up to the walls of Damietta.