A History of the Crusades-Vol 3 (33 page)

When Jenghiz-Khan and his armies returned

to Mongolia, Jelal ad-Din the Khwarismian left his exile in India and collected

round him the considerable remains of his father’s armies. He was welcomed in

Persia as a liberator from the Mongols. By 1225 he was master of the Persian

plateau and Azerbaijan, and by 1226 he was overlord of Baghdad. His kingdom, by

threatening the Ayubites, was a useful factor in the policy of the Franks of

Syria; but the Christians further north found him a worse neighbour even than

the Mongols. In 1225 he invaded Georgia. The Georgian sovereign, George IV’s

sister Russudan, an unmarried but not a virgin Queen, sent an army to meet him.

But the flower of Georgian chivalry had fallen four years before at Khunani.

Her troops were easily defeated at Garnhi, on her southern frontier. While the

Queen fled herself to Kutais, Jelal ad-Din occupied and sacked her capital of

Tiflis, and annexed the whole valley of the Kur river. An attempt by the

Georgians to recover their lost provinces in 1228 ended in disaster. The

Georgian kingdom was reduced to its lands by the Black Sea. It was no longer of

value as the north-east outpost of Christendom, nor as a power that could challenge

the Moslem hold on Asia Minor.

It was not long before the Mongols

returned to the west. A Chin revolt had first to be suppressed in northern

China. But early in 1231 a huge Mongol army under the general Chormaqan

appeared in Persia. The memory of the previous Mongol invasion served him well.

As he marched from Khorassan to Azerbaijan, there was no resistance. Jelal

ad-Din fled before him, to die obscurely in Kurdistan. His Khwarismian soldiers

followed him in his flight, and regrouped themselves in the Jezireh, out of

reach, for the moment, of the Mongol hordes. Thence they hired themselves out

to the quarrelling Ayubites, till their final destruction near Homs in 1246.

Chormaqan annexed all northern Persia and Azerbaijan to the Mongol Empire, and

governed the province, from 1231 to 1241, from a camp in Mughan, near the

Caspian Sea. In 1236 he invaded Georgia. Queen Russudan had reoccupied Tiflis

after the fall of Jelal ad-Din; but she fled once more to Kutais, and the

Mongols took over eastern Georgia. The Georgians, once the atrocities of the

conquest were over, much preferred them to the Khwarismians because of the

efficiency of their administration. In 1243 the Queen herself became their

vassal on the understanding that the whole Georgian kingdom was to be given to

her son to rule under Mongol suzerainty.

Mongol Invasion of Europe

The Christians further to the north were

less well satisfied. In

t

he

spring of 1236 a huge Mongol army assembled north of the Aral Sea, under the

command of Batu, son of Juji, whose appanage included those steppes. With Batu

were his brothers and four of his cousins, Guyuk and Qadan, sons of Ogodai,

Baidar, son of Jagatai, and Mongka, son of Tului. The aged general Subotai was

sent as chief of staff. After suppressing the Turkish tribes by the Volga, the

Mongol army marched into Russian territory in the autumn of 1237. Riazan was

taken by assault on 21 December, and its prince and all its citizens massacred.

Kolomna fell a few days later; and early in the new year the Mongols attacked

the great city of Vladimir. It held out for only six days, and its fall, on 8

February 1238, was marked by another wholesale massacre. Suzdal was sacked

about the same time, and there followed the capture and destruction of the

secondary cities of central Russia, Moscow, Yuriev, Galich, Pereslav, Rostov

and Yaroslavl. On 4 March the Grand Prince Yuri of Vladimir, was defeated and

killed on the banks of the river Sitti. Tver and Torzhok fell soon after the

battle, and the conquerors advanced over the Valdai hills towards Novgorod.

Fortunately for that city, the spring rains flooded the marshes all around.

Batu retired, to spend the rest of the year stamping out the last resistance of

the Kipchaks, while his cousin Mongka conquered the Alans and the north

Caucasian tribes, then made a raid of reconnaissance as far as Kiev.

In the autumn of 1240 Batu led the main

Mongol army into the Ukraine. Chernigov and Pereislavl were sacked and Kiev,

after a valiant defence, was taken by assault on 6 December. Many of its

greatest treasures were destroyed, and most of its population slain, though the

commander of the garrison, Dmitri, was spared because of his courage, which

Batu admired. From Kiev a branch of the army, under Baidar, son of Jagatai,

moved northwards into Poland, sacking Sandomir and Cracow. The Polish King

summoned the Teutonic Knights settled on the Baltic coast to his aid; but their

joint armies, under Duke Henry of Silesia, were routed after a fierce battle at

Wahlstadt, near Liegnitz, on 9 April 1241. But Baidar did not venture to

penetrate further westward. He devastated Silesia, then turned south, through

Moravia into Hungary.

Batu and Subotai had meanwhile crossed

into Galicia, driving before them a horde of terrified fugitives from every

nation of the steppes. In February 1241, they passed over the Carpathians into

the Hungarian plain. King Bela led his army out to meet them and was

disastrously defeated on 11 April by the bridge of Mohi, on the river Sajo. The

Mongols poured over Hungary, into Croatia and as far as the shores of the

Adriatic. Batu remained himself for some months in Hungary, which he seems to

have wished to annex to the Mongol Empire. But early in 1242 messengers arrived

with the news that the Great Khan Ogodai had died at Karakorum on 11 December

1241.

1242: The Mongols in Asia Minor

Batu could not afford to be away from

Mongolia while the succession was decided. During the Russian campaign he had

quarrelled bitterly with his cousins, Guyuk, son of Ogodai, and Buri, grandson

of Jagatai. Both had retired angrily home. Ogodai supported Batu against his

own son, whom he sent disgraced into exile. But Guyuk, as the Khan’s eldest

son, was still powerful. Ogodai named as his successor his grandson, Shiremon,

whose father, Kuchu, had been killed fighting against the Chinese. Shiremon

was, however, young and untried. Ogodai’s widow, the Khatun Toragina, born a

Naiman princess, took over the regency, determined that Guyuk should have the

throne. She summoned a Kuriltay, but, though her authority was recognized till

a new Great Khan should be appointed, five years passed before she could induce

the princes of the blood and the clan-chieftains to accept Guyuk. During these

years she administered the government. She was energetic but avaricious. Though

a Christian by birth, she chose as her favourite a Moslem, Abd ar-Rahman, whom

gossip accused of having hurried Ogodai’s death. His corruption and greed made

him universally disliked; but no one had sufficient power to upset the regency.

Till the succession was certain, Batu was

unprepared to indulge in western adventures. He maintained garrisons in Russia,

but central Europe was given a respite. It was only in western Asia, where the

Regent sent as governor an able and active general, called Baichu, that the

Mongol advance continued.

Late in 1242, Baichu invaded the lands of

the Seldjuk Sultan, Kaikhosrau, who was at that moment in the Jezireh seeking

to annex lands left masterless after Jelal ad-Din’s collapse. Erzerum fell to

the Mongols in the early spring. On 26 June 1243, the Sultan’s army was routed

at Sadagh, near Erzinjan; and Baichu advanced to Caesarea-Mazacha. Kaikhosrau

then made his submission and accepted Mongol suzerainty. His neighbour, King

Hethoum the Armenian, hastened to follow his example.

It might have been expected that the

princes of Western Christendom would have planned concerted action against so

terrible a menace. Already in 1232, when Chormaqan had destroyed the

Khwarismian power in Persia, the Assassin Order, whose headquarters at Alamut,

in the Persian mountains, was threatened, had sent envoys to Europe to warn the

Christians and to ask for help. In 1241, when it seemed that central Europe was

doomed, Pope Gregory IX urged a great alliance for its rescue. But the Emperor

Frederick, now busily engaged in conquering the Papal States in Italy, refused

to be deflected. He ordered his son Conrad, as ruler of Germany, to mobilize

the German army, and he appealed for assistance from the Kings of France and

England. When, next year, the Mongols retired into Russia, Western Christendom

returned to its illusions. The legend of Prester John spread an almost

apocalyptic belief that salvation was coming from the East, which left too

strong a mark. No one paused to reflect that if Wang-Khan the Kerait had really

been the mysterious Johannes, his destroyer was unlikely to fulfil the same

role. Everyone preferred to remember that the Mongols had fought against the

Moslems and that Christian princesses had married into the Imperial family. The

Great Khan of the Mongols might not be a Christian himself; he might not

actually be Prester John; but it was hopefully assumed that he would be eager

to champion Christian ideology against the forces of Islam. The presence in the

Eastern background of so mighty a potential ally made the moment seem ripe for

a new Crusade; and a willing Crusader was at hand.

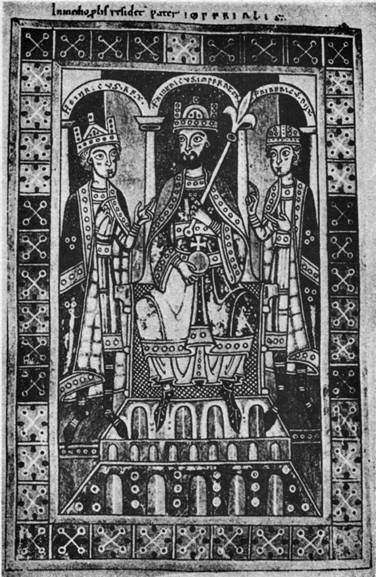

Plate

I. The Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and his sons, Henry VI, King of the Romans

and Frederick, Duke of Swabia.

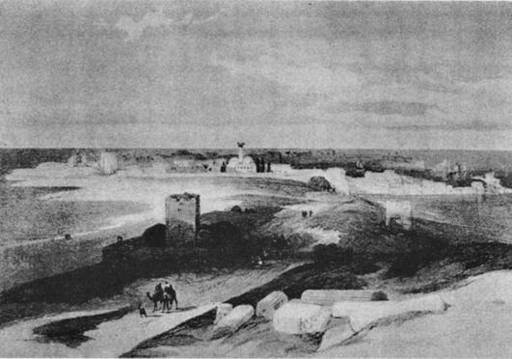

Plate

II. Constantinople from the Asiatic coast. The sea of Marmara is on the left,

the Bosphorus on the right, and the Golden Horn in the centre. The land-walls

of the city can be seen stretching from the Marmora to the Golden Horn in the

background.

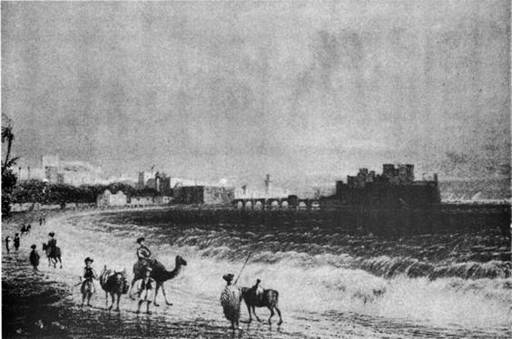

Plate

III. View of Tyre, 1839. The sandy spit joining the city to the mainland was

much narrower in medieval times.

Plate

IV. Sidon. The Castle of the Sea is on the right, and the castle repaired by

Saint Louis on the left.