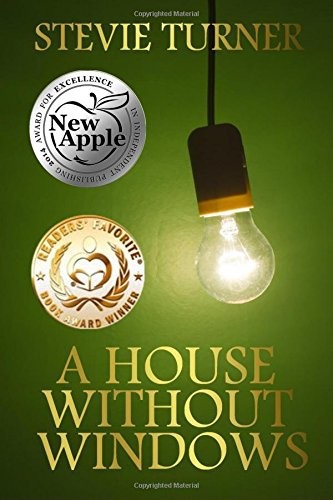

A House Without Windows

Read A House Without Windows Online

Authors: Stevie Turner

A NOVEL BY

STEVIE TURNER

COPYRIGHT 2014 STEVIE TURNER

Dr Beth Nichols thinks she may have been held captive by Edwin Evans for about 8 or 9 years now. Amidst her grief she often thinks back to happier times with her fiancée Liam; theirs was the greatest romance of all. She lays awake at night staring at the one light bulb that is never switched off, and prays that Liam is still out there somewhere searching for her……………..

OTHER BOOKS BY STEVIE TURNER:

THE PORN DETECTIVE

THE PILATES CLASS

NO SEX PLEASE, I’M MENOPAUSAL!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks again to Libbie Gran

t for the cover, and my gratitude goes to Enid Blyton for writing the Island of Adventure and starting me out on my love of reading all those years ago.

All names and characters are fictitious. Any similarity to persons living or deceased is purely coincidental.

The unprepossessing exterior of the suburban 1930’s end-of-terrace house was giving nothing away. Inspector John Hatton pushed past the usual group of ghouls and rubberneckers, dipped his slightly overweight body under the cordon, and opened the gate leading to the tidy pocket-handkerchief front garden.

“Morning Ford.”

“Morning Sir.”

“You get all the best jobs don’t you? Anyone in or out?”

“Not as far as I know, Sir.”

“Have you had a word with the neighbours?”

“The ones I’ve spoken to say he was always a bit of a loner; kept himself to himself. They don’t really know much about him.”

Stamping his feet as he sheltered from the January chill in the half–enclosed front porch, Ford looked to Hatton as though he was freezing his arse off. Hatton let a faint smile play around his lips as he realised that yes, this morning there

was

actually somebody worse off than him.

He curbed the impulse to wipe his feet on the welcome mat just inside the front door. Grimacing at the irony, he put on plastic overshoes and gloves and continued down the hallway into the kitchen.

Everything was still in its place, modern and clean. The door to the dishwasher was open as though it had been in the process of being emptied; there were still clean plates, bowls, and pots and pans stacked neatly. Knives, forks and spoons filled the cutlery compartment, all with their handles facing the same way. Hatton noticed the five large plastic containers still standing side by side above the dishwasher on the worktop, each full to the brim with a different breakfast cereal.

He could imagine guests (if there had ever been any) popping into the kitchen for a drink of water and wondering why somebody living on his own would have wanted to buy so many containers of cereal, and why they would have required such a huge American walk-in fridge. He opened the fridge door that stood next to the dishwasher; there were seven pints of full-fat milk in the storage space in the door, three large portions of raw fillet steak on the bottom shelf, and numerous types of vegetables, salad stuff and fruits filling the middle two. Various yoghurts sat on the top shelf in regimented lines, segregated into flavours, with the ones nearest their sell-by date at the front. Twelve raw eggs sat in holders slightly too small for them in the door above the milk.

Hatton took one last glance at the food that would soon begin to spoil;

he could have just eaten that fillet steak with some chips, mushrooms and peas.

Walking around the central table he noticed the dishcloth folded neatly on the draining board, not just thrown down as he would have done. He opened the cupboards underneath the sink; bleach, Dettol, and washing-up liquid stood one behind the other on the left side, next to two large packets of sanitary towels on the right.

He sighed and closed the cupboard and looked around some more. Adjacent to the sink stood a washing machine still full of damp women’s clothing, and on the far wall was a long clean-looking worktop with cupboards underneath containing sweets and crisps, and what looked like a pantry just outside the kitchen door. Hatton checked inside and found shelves overflowing with rice, spaghetti, pasta, potatoes, more tinned food, and the door to what resembled yet another American type of walk-in-fridge, silver in colour, but built into a recess with a bolt on the outside. The bolt was pulled back into the open position, and the door was slightly ajar. He walked towards it, opened the door fully, and trod carefully down the narrow flight of steps.

He had to see it just once more, before the house was bulldozed and razed to the ground.

Mummy wonders if it will be Christmas soon, but I don’t know what she means. She says that when she was a little girl she would get lots of presents on Christmas Day, and there would be a big tree in her house with lots of twinkling fairy lights on the branches and shiny baubles that she could see her reflection in. I’ve never seen a tree, so Mummy drew one for me in my colouring book and showed me. I don’t understand why there was a tree in her house.

My name is Amy, and Mummy thinks I could be seven, eight or nine years old because my big front teeth are growing in. I have long blonde hair like Mummy that I can sit on. Mummy puts it in a plait and she showed me how to plait hers, and she taught me how to read. She says I can read and write really well, and I like writing stories. I write everything down in a secret diary and keep it under the mattress. Mummy writes things down too. The Man brings us paper, pencils, exercise books, and colouring books for me, but he doesn’t speak much. Mummy tells me to keep out of his way, so I run to the toilet when he comes. Sometimes he finds me and smiles, and says that I’m getting a big girl. I don’t like him. He’s nearly as tall as the ceiling and he has hair all over his face. Mummy told me his name is Edwin, but I don’t like him so I call him

The Man.

Our house is small and dark. There’s a light bulb hanging from the ceiling that stays on all the time, even when we go to sleep. It’s too dark without the light on, and I get frightened. I get in bed with Mummy because there’s nowhere else to sleep. When I lay in bed I can see all the rest of the house except the toilet and sink, which is around a little corner and out of the way. All the walls are greenish-grey, and Mummy says they’re made out of concrete. When I touch them they’re cold.

Mummy sticks my pictures on the walls with something called Blu-tack, and she says they brighten things up a bit. My best picture is the one of Prince, a ginger cat that sometimes follows behind The Man when he brings our food. I’m allowed to stroke Prince until he goes back out, but then Mummy says I have to wash my hands before I eat anything.

Last week The Man brought me a reading book. I’d never had a reading book before. He said I had to look after it because he’d kept it safe for years since he was a little boy. It’s got thick pages, large letters, and a sort of yellowy cardboard cover. I’ve started to read it. A lady called Enid Blyton wrote it, and it’s called The Island of Adventure. It begins where a boy called Philip who loves animals is at some sort of summer school and is bored as he sits under a tree doing something called algebra (I asked Mummy what algebra is, and she said it’s a different kind of maths). He hears a strange voice telling him to blow his nose and wipe his feet. It turns out the voice comes from a parrot sitting in a tree nearby, and he follows it as it flies off down the hillside back towards his school. That’s the only bit I’ve read so far.

I asked Mummy what a parrot is, and why I can’t sit under a tree. She told me a parrot is a colourful bird that flies around in hot countries, but that some people in this country keep them in cages as pets. I think that’s cruel. If I had a parrot I’d let it fly about.

I had to ask her again why I can’t sit under a tree. Mummy sighed and told me that trees grew outside, and we weren’t allowed to go outside. When I asked her why, she said that The Man doesn’t want us to.

It’s boring in our house. I do maths with Mummy like Philip had to do at school. I know how to add up lots of numbers in my head and come up with the right answer, and Mummy says not many eight year olds can do that. She always asks me to spell words and read even longer words. She helps me with the ones I can’t do, because she’s a doctor and she’s cleverer than me. When my felt tips run out I have to wait for The Man to bring more. There’s no parrots flying around to look at, and I want to sit under a tree. One day I will get outside, but I’m not sure yet how I’ll go about doing it.

CHAPTER 2

The Man brought us some food a little while ago, but the sound of the bolt and keys turning in the outer door tells me he is coming in again. I can hear him locking the door behind him. Mummy jumps up and tells me to run and hide in the toilet, and not to come out until she tells me to.

I don’t need to do a wee, so I sit on the plastic seat with my reading book. The light isn’t very good in the toilet, and I have to hold the book close to my face. I hear the key opening the door to our house, and I hear footsteps on the bit of floor just inside the door that hasn’t got any rough brown carpet on it.

I can’t hear Mummy saying anything. I can hear the rustle of some sort of material, and after a while I can hear the noise that our bedsprings make when we wake up and turn over.

Nobody speaks, but I can hear The Man grunting away. Is he asleep? Mummy tells me never to come out of the toilet when he’s here, but I can’t see to read much and I want to find out why he’s grunting. Perhaps if he’s fallen asleep we can run to the door and get outside.

I put down my book and creep on tiptoe to the end of the wall and look around the corner. As soon as I do I want to cry, and wish I’d listened to Mummy.

Mummy’s eyes were closed. She was lying on her back and she looked sad. She had no clothes on and neither did The Man. I’ve never seen Mummy without any clothes on before. She has big boobs. I don’t have any at all. The Man was fat and he was kneeling over her. Her hair had been taken out of its plait and was spread all over the pillow. I could see his bum moving backwards and forwards, but his face was pointing up towards the ceiling.

I run back to the safety of the toilet seat and cuddle my book close. My heart is beating fast, and it takes a long time to slow down. I try and work out why Mummy wants The Man to see her without any clothes on when she’s always telling me that we have to cover up our private places.

The grunting stops and the bedsprings creak. I hear rustling again and footsteps going towards the door. The keys jangle, the door opens, but then closes quickly. I hear The Man locking it and walking to the outer door. The key turns in the lock, and then there’s the sound of the other door being slammed shut and locked, and then the sound of a bolt being slid across.

Mummy comes into the toilet. Holding onto my book I look down on the floor, because I don’t want to see her without anything on. She lifts my chin up and smiles, but her eyes are sad. She has all her clothes back on. She says she needs a wee, and if I could sit on the bed then she will hear me read in a minute.

I skip to the bed, happy that The Man has gone. There is the sound of the sink filling up and splashing noises, and then Mummy is back with me.

I open the book. Philip runs back to school and meets Lucy-Ann. She has ginger hair like Prince. She’s Jack’s sister and has come to the school just to be with Jack in the summer holidays. I wish I had a brother or sister or a parrot. Jack loves birds and doesn’t want to be at the school. He owns the parrot, whose name is Kiki. She’s tame and sits on his shoulder. Jack is about fourteen, which is really old. He is older than me and Philip and Lucy-Ann. Philip has a sister called Dinah who is twelve and lives with their Aunt Polly at a big house near the sea called Craggy-Tops. I ask Mummy where the sea is, and she says there’s lots and lots of salty water that’s all around the British Isles where we live, and that water is the sea.

I want to see the sea, see the sea, and see the sea again. Mummy says I’m a very clever girl. I could even read the word ‘ornithologist’ in the book, but I don’t know what it means. Because Mummy is a doctor she knows what everything means. She tells me it’s somebody that likes and studies birds, and knows a lot about them. I’ve never seen a real bird. Jack wants to be an ornithologist when he grows up. I think I’ll be one too and then I can have a parrot.