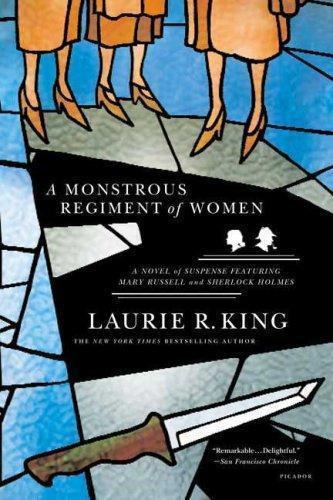

A Monstrous Regiment of Women

Read A Monstrous Regiment of Women Online

Authors: Laurie R. King

A Monstrous Regiment of Women

Laurie R. King

MARY RUSSELL-SHERLOCK HOLMES 02

A 3S digital back-up edition 1.0

click for scan notes and proofing history

Contents

Editor’s Preface

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

|

13

|

14

|

15

|

16

|

17

|

18

|

19

|

20

|

21

|

Postscript

St. Martin’s Press - New York

Previous books by Laurie R. King

Also about Mary Russell

The Beekeeper’s Apprentice

and about Kate Martinelli

To Play the Fool

A Grave Talent

A

MONSTROUS REGIMENT OF WOMEN

. Copyright © 1995 by Laurie R. King. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

King, Laurie R.

A monstrous regiment of women / Laurie R. King

p. cm.

“A Thomas Dunne book.”

ISBN 0-312-13565-3

1. Holmes, Sherlock (Fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Women detectives—England—London—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3561.I4813M66 1995

813'.54—dc20 95-21088

CIP

First edition: September 1995

for Zoe

τό φω̃ς των άνθρώπων

EDITOR’S PREFACE

The story between these covers is the second I have resuscitated from the bottom of a tin trunk that I received anonymously some years ago. In my editor’s introduction to the first, which was given the name

The Beekeeper’s Apprentice

, I admitted that I had no idea why I had been the recipient of the trunk and its contents. They ranged in value from an emerald necklace to a small worn photograph of a thin, tired-looking young man in a WWI army uniform.

There were other intriguing objects as well: The coin with a hole drilled through it, for example, heavily worn on one side and scratched with the name

IAN

on the other, must surely tell a story; so, too, the ragged shoelace, carefully wound and knotted, and the short stub of a beeswax candle. But the most amazing thing, even for someone like myself who is no particular Sherlock Holmes scholar, are the manuscripts.

The Beekeeper’s Apprentice

told of the early days of a partnership heretofore unknown to the world: that of young Mary Russell and the middle-aged and long-retired Sherlock Holmes.

These literally are

manuscripts

, handwritten on various kinds of paper. Some of them were easy enough to decipher, but others, two of them in particular, were damned hard work. This present story was the worst. It looked as if it had been rewritten a dozen or more times, with parts of pages torn away, scraps of others inserted, heavy cross-hatching defying all attempts at bringing out the deleted text. This was not, I think, an easy book for Ms. Russell to write.

As I said, I have no idea why this collection was sent to me. I believe, however, that the sender, if not the author herself, may still be alive. Among the letters generated by the publication of

The Beekeeper’s Apprentice

was an odd and much-travelled postcard, mailed in Utrecht. It was an old card, with a sepia photograph of a stone bridge over a river, a long flat boat with a man standing at one end holding a pole and a woman in Edwardian dress sitting at the other, and three swans. The back was printed with the caption,

FOLLY BRIDGE, OXFORD

. Written on it, in handwriting similar to that of the manuscripts, was my name and address, and beside that the phrase, “More to follow.” I certainly hope so.

—Laurie R. King

For who can deny that it is repugnant to nature that the blind shall be appointed to lead and conduct such as do see, that the weak, the sick and the impotent shall nourish and keep the whole and the strong, and, finally, that the foolish, mad, and frenetic shall govern the discrete and give counsel to such as be sober of mind? And such be all women compared to man in bearing of authority.

—John Knox (1505-1572)

The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women

(Published in 1558 against Mary Tudor; later applied to Mary Stuart.

Regiment

is used in the sense of

régime

.)

ONE

Sunday, 26 December-

Monday, 27 December

Womankind is imprudent and soft or flexible. Imprudent because she cannot consider with wisdom and reason the things she hears and sees; and soft she is because she is easily bowed.

—John Chrysostom (c.347-407)

I sat back in my chair, jabbed the cap onto my pen, threw it into the drawer, and abandoned myself to the flood of satisfaction, relief, and anticipation that was let loose by that simple action. The satisfaction was for the essay whose last endnote I had just corrected, the distillation of several months’ hard work and my first effort as a mature scholar: It was a solid piece of work, ringing true and clear on the page. The relief I felt was not for the writing, but for the concomitant fact that, thanks to my preoccupation, I had survived the compulsory Christmas revels, a fête which had reached a fever pitch in this, the last year of my aunt’s control of what she saw as the family purse. The anticipation was for the week of freedom before me, one entire week with neither commitments nor responsibilities, leading up to my twenty-first birthday and all the rights and privileges pertaining thereto. A small but persistent niggle of trepidation tried to make itself known, but I forestalled it by standing up and going to the chest of drawers for clothing.

My aunt was, strictly speaking, Jewish, but she had long ago abandoned her heritage and claimed with all the enthusiasm of a convert the outward forms of cultural Anglicanism. As a result, her idea of Christmas tended heavily towards the Dickensian and Saxe-Gothan. Her final year as my so-called guardian was coincidentally the first year since the Great War ended to see quantities of unrationed sugar, butter, and meat, which meant that the emotional excesses had been compounded by culinary ones. I had begged off most of the revelry, citing the demands of the paper, but with my typewriter fallen silent, I had no choice but crass and immediate flight. I did not have to think about my choice of goals—I should begin at the cottage of my friend and mentor, my tutor, sparring partner, and comrade-in-arms, Sherlock Holmes. Hence my anticipation. Hence also the trepidation.

In rebellion against the houseful of velvet and silk through which I had moved for what seemed like weeks, I pulled from the wardrobe the most moth-eaten of my long-dead father’s suits and put it on over a deliciously soft and threadbare linen shirt and a heavy Guernsey pullover I had rescued from the mice in the attic. Warm, lined doeskin gloves, my plaits pinned up under an oversized tweed cap, thick scarf, and a pause for thought. Whatever I was going to do for the next three or four days, it would be at a distance from home. I went to the chest of drawers and took out an extra pair of wool stockings, and from a secret niche behind the wainscotting I retrieved a leather pouch, in which I had secreted all the odd notes and coins of unspent gifts and allowances over the last couple of years—a considerable number, I was pleased to see. The pouch went into an inner pocket along with a pencil stub, some folded sheets of paper, and a small book on Rabbi Akiva that I’d been saving for a treat. I took a last look at my refuge, locked the door behind me, and carried my rubber-soled boots to the back door to lace them on.

Although I half-hoped that one of my relatives might hail me, they were all either busy with the games in the parlour or unconscious in a bloated stupor, because the only persons I saw were the red-faced cook and her harassed helper, and they were too busy preparing yet another meal to do more than return my greetings distractedly. I wondered idly how much I was paying them to work on the day a servant traditionally expected to have free, but I shrugged off the thought, put on my boots and the dingy overcoat I kept at the back of the cupboard beneath the stairs, and escaped from the overheated, overcrowded, emotion-laden house into the clear, cold sea air of the Sussex Downs. My breath smoked around me and my feet crunched across patches not yet thawed by the watery sunlight, and by the time I reached Holmes’ cottage five miles away, I felt clean and calm for the first time since leaving Oxford at the end of term.

He was not at home.

Mrs Hudson was there, though. I kissed her affectionately and admired the needlework she was doing in front of the kitchen fire, and teased her about her slack ways on her free days and she tartly informed me that she wore her apron only when she was on duty, and I commented that in that case she must surely wear it over her nightdress, because as far as I could see she was always on duty when Holmes was about, and why didn’t she come and take over my house in seven days’ time and I’d be sure to appreciate her, but she only laughed, knowing I didn’t mean it, and put the kettle on the fire.

He had gone to Town, she said, dressed in a multitude of mismatched layers, two scarfs, and a frayed and filthy silk hat—and did I prefer scones or muffins?

“Are the muffins already made?”

“Oh, there are a few left from yesterday, but I’ll make fresh.”

“On your one day off during the year? You’ll do nothing of the sort. I adore your muffins toasted—you know that—and they’re better the second day, anyway.”

She let herself be persuaded. I went up to Holmes’ room and conducted a judicious search of his chest of drawers and cupboards while she assembled the necessaries. As I expected, he had taken the fingerless gloves he used for driving horses and the tool for prising stones from hoofs; in combination with the hat, it meant he was driving a horsecab. I went back down to the kitchen, humming.

I toasted muffins over the fire and gossiped happily with Mrs Hudson until it was time for me to leave, replete with muffins, butter, jam, anchovy toast, two slices of Christmas cake, and a waxed paper-wrapped parcel in my pocket, in order to catch the 4:43 to London.

I used occasionally to wonder why the otherwise-canny folk of the nearby towns, and particularly the stationmasters who sold the tickets, did not remark at the regular appearance of odd characters on their platforms, one old and one young, of either sex, often together. Not until the previous summer had I realised that our disguises were treated as a communal scheme by our villagers, who made it a point of honour never to let slip their suspicions that the scruffy young male farmhand who slouched through the streets might be the same person who, dressed considerably more appropriately in tweed skirt and cloche hat, went off to Oxford during term time and returned to buy tea cakes and spades and the occasional half-pint of bitter from the merchants when she was in residence. I believe that had a reporter from the

Evening Standard

come to town and offered one hundred pounds for an inside story on the famous detective, the people would have looked at him with that phlegmatic country expression that hides so much and asked politely who he might be meaning.