A More Perfect Heaven (2 page)

Read A More Perfect Heaven Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

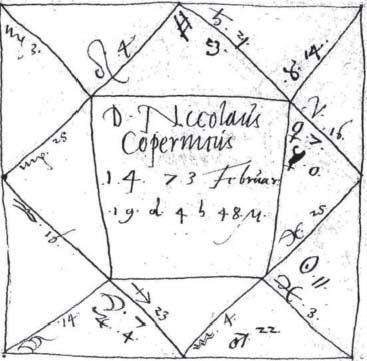

HOROSCOPE FOR NICOLAUS COPERNICUS

Astronomers and astrologers in Copernicus’s time shared the same pool of information about the positions of the heavenly bodies against the backdrop of the stars. Until the invention of the telescope in the seventeenth century, position finding and position predicting constituted the entirety of planetary science—and the basis for casting horoscopes.

He was christened for his father—Mikolaj in Polish, Niklas in German, his native tongue. Later, as a scholar, he Latinized his name, but he grew up Niklas Koppernigk, the second son and youngest child of a merchant family from the copper-mining regions of Silesia. Their ancestral village of Koperniki could have taken its name from the Slavic word for the dill plant,

koper

, or from the Old German term for the metal mined there,

kopper

—or maybe it commemorated both those products of its hillsides. In any case, the roots of Koperniki’s etymology lay long buried by the time its younger generations began leaving home to seek new fortunes in the towns and cities. An armorer named Mikolaj Kopernik appeared in the city chronicles of Krakow in 1375, followed by mention of the mason Niclos Kopernik in 1396 and the rope maker Mikolaj Kopernik in 1439, all bearing the names of their forefathers’ homeland and its popular patron saint.

Around the year 1456, the alderman Mikolaj Koppernigk, who traded in Hungarian copper, moved north from Krakow to Torun, where he married Barbara Watzenrode. They lived on narrow St. Anne’s Lane, later renamed Copernicus Street, and raised four children in a tall brick house that is now a museum to the memory of their famous son. From the double front doors under the house’s pointed arch, their two boys, Andrei and Niklas, could walk to classes at the parish school of St. John’s Church, or down to the family warehouse near the wide river, the Vistula, that coursed from Krakow past Warsaw through Torun, carrying the flow of commerce to Danzig on the Baltic Sea.

Soon after the boy Niklas reached ten years of age, the elder Niklas died. His bereft sons and daughters and his widow, Barbara Koppernigk, turned for succor to her brother, Lukasz Watzenrode, a minor cleric, or “canon,” in a nearby diocese. Or perhaps Barbara, whose date of death is not recorded, had predeceased her husband, leaving her brood true orphans. Either way, the children came under their uncle’s care. Canon Watzenrode arranged a marriage contract for his niece Katyryna with Bartel Gertner of Krakow and consigned his niece Barbara to the Cistercian convent at Kulm. His young nephews he supported at school, first in Torun and later in Kulm or Wloclawek, until they were ready to attend his alma mater, the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. By then Uncle Lukasz had risen from a mediocre position in the Catholic hierarchy to become Bishop of Varmia.

A page of Gothic script in the archives of the Collegium Maius at the Jagiellonian University attests that Nicolaus Copernicus, age eighteen, paid his tuition fees in full for the fall of 1491. He studied logic, poetry, rhetoric, natural philosophy, and mathematical astronomy. According to the courses in his curriculum, his father’s copper and other common substances could not be considered elements in the modern sense of the periodic table. Rather, they comprised some combination of the four classic elements: earth, water, air, and fire. The heavens, in contrast, consisted entirely of a fifth essence, called ether, which differed from the other four by virtue of being inviolate and everlasting. Ordinary objects on Earth moved more or less along straight paths, whether seeking their natural places in the world order or being compelled by outside agents. Heavenly bodies, however, lay cocooned in celestial spheres that spun in eternal perfect circles.

The motions of the planets captured Copernicus’s interest from the start of his university studies. At college he purchased two sets of tables for calculating their positions and had these bound together, adding sixteen blank pages where he copied parts of a third table and wrote miscellaneous notes. (This custom volume and other remnants of his personal library, seized as spoils of the Thirty Years’ War, now belong to the University of Uppsala, Sweden. (Copernicus more than once explained his attraction to astronomy in terms of beauty, asking rhetorically,

“What could be more beautiful than the heavens, which contain all beautiful things?”

He also cited the “unbelievable pleasure of mind” he derived from contemplating “things established in the finest order and directed by divine ruling.”

“Among the many various literary and artistic pursuits upon which the natural talents of man are nourished,”

he wrote, “I think the ones above all to be embraced and pursued with the most loving care concern the most beautiful and worthy objects, most deserving to be known. This is the nature of the discipline that deals with the godlike circular movements of the world and the course of the stars.”

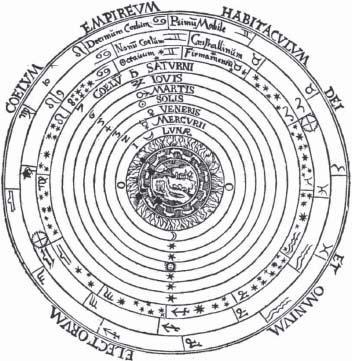

ARISTOTLE’S UNIVERSE

As Copernicus learned in school, the world around him consisted of the four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. Far removed from these ordinary substances, the Moon and other celestial bodies consisted of a fifth essence, immune to change or destruction. In the perfect heavens, bodies moved with uniform circular motion.

The portrait of him now hanging in Torun’s town hall cuts a youthful, handsome figure. Based on a purported self-portrait that disappeared long ago, it shows Copernicus dressed in a red jerkin, with glints painted into his dark eyes and dark hair. (The light in each brown iris reflects, on close inspection, the tall Gothic windows of the rooms he frequented.) He had a long nose, a manly shadow above his full lips, and a faint scar extending from the corner of his left eye up into the eyebrow. This mark encouraged archaeologists in 2005, who picked out his skull among the litter of remains under the church where he had lain buried. A double dent above the skull’s right eye socket—not the left one—seemed to affirm their identification, since every portraitist sees himself as his mirror’s image.

In September 1496, again at his uncle’s command, Copernicus traveled to Italy to study canon law, concerning the rights and duties of the clergy, at the University of Bologna. Only one year into this enterprise, he became a canon himself. The death of one of the sixteen Varmia canons created a vacancy, and Bishop Watzenrode used his connections to win Copernicus the office in absentia. As the fourteenth canon of the Cathedral Chapter—effectively a trustee in the rich and powerful governing body of the Varmia diocese—Copernicus could now collect an income independent of his allowance.

He lodged in Bologna with the local astronomy professor, Domenico Maria Novara, whom he assisted in nightly observations. Together they watched the Moon pass in front of the bright star Aldebaran (the eye of Taurus the Bull) on March 9, 1497, and Copernicus recorded in his notes how the star hid

“between the horns of the moon at the end of the fifth hour of the night.”

At the conclusion of his law studies, he visited Rome in the summer of 1500 for the jubilee year celebrations. He and other pilgrims tripled the population of the Holy City, where a crowd of two hundred thousand knelt to receive the Easter Sunday blessing of Pope Alexander VI. Still in Rome on November 6, Copernicus observed and recorded a partial lunar eclipse. He also lectured in Rome about mathematics to students and experts alike. But his future with the Church had already been decided. July 27, 1501, found him at a meeting of the Cathedral Chapter in Varmia, along with his older brother, Andreas, who had also attained a canonry there, courtesy of Uncle Lukasz. Both young men requested leave to return to Italy for further education and received the chapter’s blessing. They set out almost immediately for Padua, where Copernicus studied medicine in preparation for a career as “healing physician” to the bishop and canons of Varmia.

THE ZODIAC

The Earth-centered universe that Copernicus inherited is pictured in this frontispiece from one of his favorite books, the

Epitome of Ptolemy’s Almagest,

by Regiomontanus. He and other astronomers measured the motions of the “wandering” stars—the planets, the Sun, and the Moon—through the band of “fixed” stars called the zodiac. The Sun took about one month to progress through each sign, completing the circuit from the ram, Aries, to the fishes, Pisces, in a year. Since the actual constellations vary considerably in size, astronomers arbitrarily assigned the same one twelfth of a circle, or 30°, to each zodiac sign.

In his novel

Doctor Copernicus

, John Banville imagines the brothers equipping themselves for their journey

“with two stout staffs, good heavy jackets lined with sheepskin against the Alpine cold, a tinderbox, a compass, four pounds of sailor’s biscuit and a keg of salt pork.”

This and other rich descriptions—one of which pictures “Nicolas” sewing gold coins into the lining of his cloak for safekeeping—leap the gaps in the true life story. Historians have pieced that together from his few published works and the scattered archives where he left his name. His lifetime of correspondence comes down today to just seventeen surviving signed letters. (Of these, three concern the woman who lived with him as cook and housekeeper, and probably concubine as well.)

“The inns were terrible, crawling with lice and rogues and poxed whores,”

Banville continues the brothers’ travel narrative. “And then one rainy evening as they were crossing a high plateau under a sulphurous lowering sky a band of horsemen wheeled down on them, yelling. They were unlovely ruffians, tattered and lean, deserters from some distant war. … The brothers watched in silence their mule being driven off. Nicolas’s suspiciously weighty cloak was ripped asunder, and the hoard of coins spilled out.” It could all have happened, just that way.

As a medical student at the University of Padua, Copernicus learned therapeutic techniques, such as bloodletting with leeches, aimed at balancing the four bodily humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. All manifestations of health or disease stemmed from an excess or deficiency of one or more of these fluids. Even gray hair was caused by “corrupt humors” and could be postponed with the proper prescription. Copernicus also watched anatomical dissections, studied surgical procedures, and took instruction in the application of astrology to diagnosis and treatment. His textbooks, which were still with him at his death and mentioned in his will, included the 1485 edition of

Breviarium practicae

by Arnaldus of Villanova, a thirteenth-century physician and alchemist.

“To produce sleep so profound that the patient may be cut and will feel nothing, as though he were dead,”

Arnaldus advised, “take of opium, mandragora bark, and henbane root equal parts, pound them together and mix with water. When you want to sew or cut a man, dip a rag in this and put it to his forehead and nostrils. He will soon sleep so deeply that you may do what you will. To wake him up, dip the rag in strong vinegar.”