A People's Tragedy (100 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

Meanwhile, however, the Bolshevik insurrection was already gaining momentum.

Despite Trotsky's call for discipline, it was hard to stop the defensive measures of the MRC from spilling into a general offensive. As darkness fell, armed crowds of Bolshevik workers and soldiers spilled into the centre of the city. The government blockades on the bridges, which controlled the routes from the outlying slums, were taken over by Red Guards. They set up road blocks and patrolled the streets in armoured cars, while late-night theatre-goers hurried home. By the early hours of the morning, Bolshevik forces had seized control of the railway stations, the post and telegraph, the state bank, the telephone exchange and the electricity station. The Red Guards had taken over the local police stations and had begun to assume the functions of the police themselves. Overall, the insurgents had the control of almost all the city with the exception of the central zone around the Winter Palace and St Isaac's Square. Bunkered inside the Winter Palace, Kerensky's ministers did not even have control over their own lights or telephones. One of the Bolshevik engineers engaged in the occupation of the Nikolaevsky Station recalled standing guard by the equestrian statue of Alexander III: It was a freezing night. One could feel the north wind going through one's Bolsheviks needed the sanction of the Soviet Congress to give legitimacy to their seizure of power: without it they could certainly not rely on the support of the soldiers and workers, and might even run the risk of having to fight against them. The Soviet delegates were already arriving for the opening of the Congress on the 25th, and from their composition it seemed highly likely that there would be a solid majority in favour of Soviet power. As for the Provisional Government — well, it was looking increasingly provisional, and would no doubt fall at the slightest prod. In the evening of the 24th the Preparliament had effectively passed a motion of no confidence in it. Even Dan and Gots, previously among the most obstinate advocates of the coalition, abandoned Kerensky and called for the establishment of a democratic government committed to peace and radical reforms. They wanted to publicize this as a historic proclamation plastered throughout the capital that same night, in the hope that it might appease the potential insurgents and strengthen the campaign for a peaceful resolution of the power question through the formation of a socialist coalition. Perhaps it was already too late for this: it looked like trying to fend off the Bolshevik guns with paper decrees. Yet, even in these final hours, there was still some basis for hope that agreement might be reached. In the evening of the 24th Kamenev was still rushing around the Smolny trying to win support for a resolution calling on the Congress to form a socialist government of all the Soviet parties; and the SRs and Mensheviks,

whose congress delegates met late into the night, were at last coming round to support the plan.

Meanwhile, however, the Bolshevik insurrection was already gaining momentum.

Despite Trotsky's call for discipline, it was hard to stop the defensive measures of the MRC from spilling into a general offensive. As darkness fell, armed crowds of Bolshevik workers and soldiers spilled into the centre of the city. The government blockades on the bridges, which controlled the routes from the outlying slums, were taken over by Red Guards. They set up road blocks and patrolled the streets in armoured cars, while late-night theatre-goers hurried home. By the early hours of the morning, Bolshevik forces had seized control of the railway stations, the post and telegraph, the state bank, the telephone exchange and the electricity station. The Red Guards had taken over the local police stations and had begun to assume the functions of the police themselves. Overall, the insurgents had the control of almost all the city with the exception of the central zone around the Winter Palace and St Isaac's Square. Bunkered inside the Winter Palace, Kerensky's ministers did not even have control over their own lights or telephones. One of the Bolshevik engineers engaged in the occupation of the Nikolaevsky Station recalled standing guard by the equestrian statue of Alexander III: It was a freezing night. One could feel the north wind going through one's IMAGES OF 1917

52 The First Provisional Government in the Marinsky Palace. Prince Lvov is seated in the centre, Miliukov is second from the right, while Kerensky is standing behind him.

Note that the tsarist portraits (of Alexander II and Alexander III) have not been removed.

53 A rare moment of national unity: the burial of the victims of the February Revolution on the Mars Field in Petrograd, 23 March 1917.

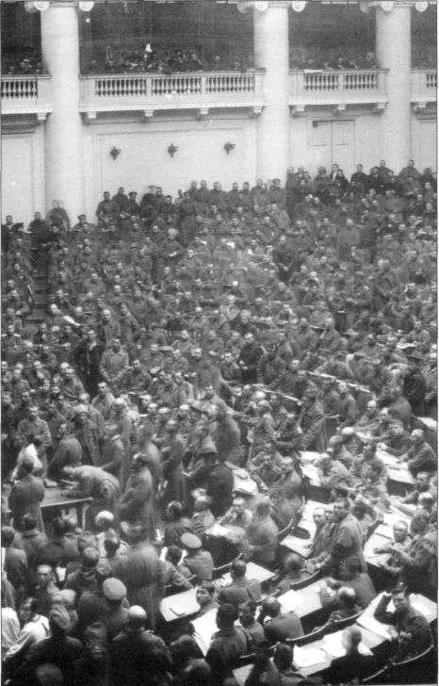

54 A meeting of the Soviet of Soldiers' Deputies in the Catherine Hall of the Tauride Palace.

55 Waiters and waitresses of Petrograd on strike. The main banner reads: 'We insist on respect for waiters as human beings.' The three other banners call for an end to the degrading practice of tipping service staff. This stress on respect for workers as citizens was a prominent feature of many strikes. Note in this context that the strikers are well dressed - they could be mistaken for bourgeois citizens - since this was a demonstration of their dignity.

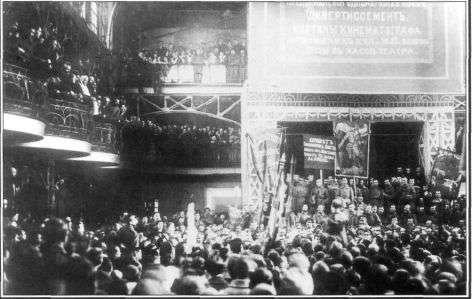

56 The All-Russian Congress of Peasant Deputies in the People's House in Petrograd, 4

May. A soldiers' delegation (standing in the hall) greets the deputies (on the balconies).

In the second balcony on the left are (

from left to right)

the four veteran SR leaders: Viktor Chernov, Vera Figner, Ekaterina Breshko-Breshkovskaya and N. D. Avksentiev.

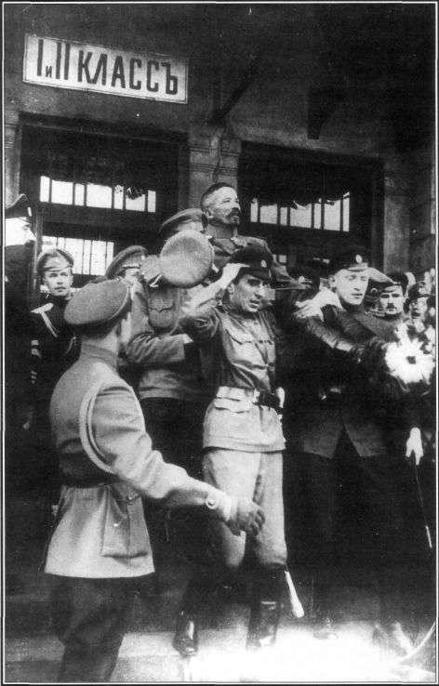

57 Fedor Linde leads the Finland Regiment to the Marinsky Palace on 20 April to protest against the continuation of the war for imperial ends.

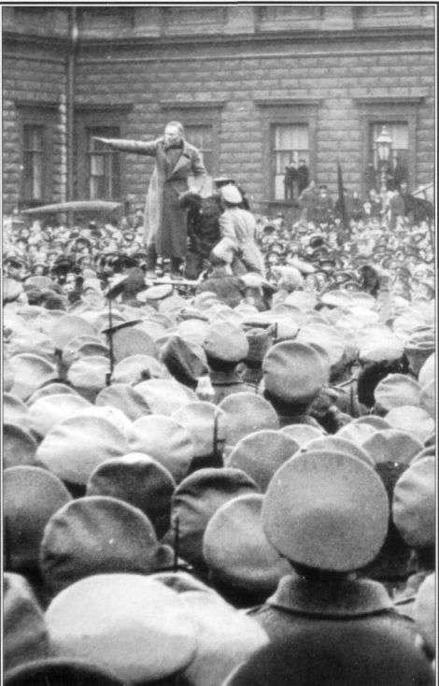

58 Kerensky cuts a Bonapartist figure during a speech in mid-May to the soldiers of the Front.

59 Metropolitan Nikon blesses the Women's Battalion of Death on Red Square in Moscow before their departure for the Front in June. One of the women was too fat for standard-issue trousers and had to go to battle in a skirt.