A People's Tragedy (141 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

94 A typical example of the new bureaucracy: the Agitation and Propaganda Department of the Commissariat for Supply and Distribution in the Northern Region.

Note the portrait of Marx, the leathered commissar, and the bourgeois daughters who served in such large numbers as secretaries.

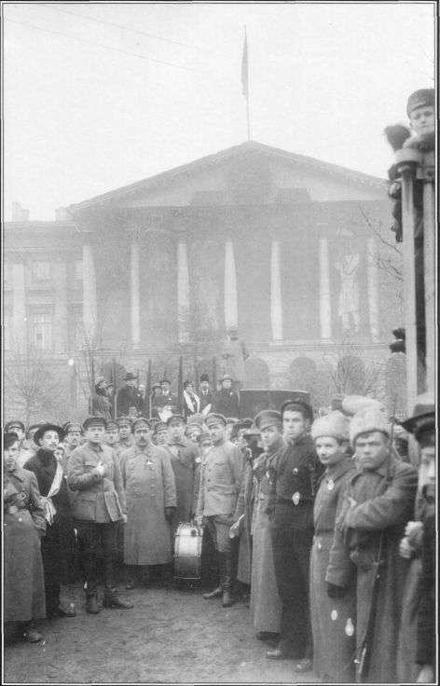

95 The Smolny Institute on the anniversary of the October coup. But it was fast becoming not so much a bastion of the Marxist revolution as one of the corruption of the party elite.

status of a hero.* Gatchina, where much of the fighting had taken place, was renamed Trotsk. It was the first Soviet town to be named after a living Communist.

* * * As Denikin's forces fled southwards they lost all semblance of discipline and began to break up in panic. Napoleon had once remarked about his own retreat from Moscow: 'from the sublime to the ridiculous it is only one step'. Much the same could be said for Denikin's.

It was not just the Reds who had caused, the Whites to panic. Makhno's partisans, Petliura's Ukrainian nationalists and various other partisan bands ambushed the White units from all sides as they retreated towards the Black Sea. Denikin's forces were passing through terrain where the local population, in Wrangel's words, 'had learned to hate us'. Then, in late November, came the shocking news that the British were ending their support for the Whites. Coupled with the news of Kolchak's defeat, this had a devastating effect on morale. 'In a couple of days the whole atmosphere in South Russia was changed,' remarked one eye-witness. 'Whatever firmness of purpose there had previously been was now so undermined that the worst became possible. [Lloyd]

George's opinion that the Volunteer cause was doomed helped to make that doom almost certain.' The optimism that had so far maintained the White movement —

Sokolov compared it to the gambler's desperate belief that his winning card would somehow turn up — now collapsed completely. Soldiers and officers deserted

en masse.

The Cossacks became disenchanted with the Whites. Many of the Kuban Cossacks refused to go on fighting unless Denikin satisfied their demands for a separate state.37

There was similar disenchantment within the huge White civilian camp. People no longer believed in victory, and thought only of how to flee abroad. Shops and cafes closed. There was a mad rush to exchange the Don roubles issued by Denikin for foreign currency. In a repeat of the panic scenes in Omsk, thousands of officers and civilians struggled to get aboard trains for the Black Sea ports. The wounded and the sick, whose numbers were swollen by a raging typhus epidemic, were simply abandoned. This could no longer be called a 'bourgeoisie on the run'. Most of the refugees were now penniless, whatever their former fortunes. It was a poor mass of naked humanity fleeing for its life. One witness saw this in the flight from Kharkov: As the last Russian hospital train was preparing to leave one evening, in the dim light of the station lamps strange figures were seen crawling along the platform. They were grey and shapeless, like big wolves. They

* And his opponents, notably Stalin, warned for the first time of the dangers of Bonapartism.

came nearer, and with horror it was recognized that they were eight Russian officers ill with typhus, dressed in their grey hospital dressing-gowns, who, rather than be left behind to be tortured and murdered by the Bolshevists, as was likely to be their fate, had crawled along on all fours through the snow from the hospital to the station, hoping to be taken away on a train.38

In the context of this moral collapse the White Terror reached its climax and the worst pogroms against the Jews were carried out. It was a last savage act of retribution against a race whom many of the Whites blamed for the revolution.

Anti-Semitism was a fact of life in Russia throughout the revolutionary period. Attacks on Jews often played a part in the violence of the crowd. The word pogrom could mean both an attack on the Jews and an assault on property in general. The tsarist regime, in stirring up the one, had always been careful not to let it spill over into the other. The scapegoating of Jews for the country's woes became much more widespread after 1914.

The Pale of Settlement was broken down by the war and the Jews dispersed across Russia. They appeared in the major cities of the north for the first time in large numbers. During the revolution Jews entered the government and official positions also for the first time. Not many Jews were Bolsheviks, but many of the leading Bolsheviks were Jews. To large numbers of ordinary Russians, whose world had been turned upside-down, it thus appeared that their country's ruin was somehow connected with the sudden appearance of the Jews in places and positions of authority formerly reserved for the non-Jews. It was a short step from this to conclude that the Jews were plotting to bring about Russia's ruin. The result was mass Judeophobia. 'Hatred of the Jews', wrote a leading sociologist in 1921, 'is one of the most prominent features of Russian life today; perhaps even the most prominent. Jews are hated everywhere — in the north, in the south, in the east, and in the west. They are hated by people regardless of their class or education, political persuasion, race, or age.'39

During the early stages of the White movement in the south anti-Semitism played a relatively minor role. There were even Jews in the Volunteer Army, some of them heroes of the Ice March. OSVAG, Denikin's propaganda organ, employed many Jews.

But as the Whites advanced into the Ukraine, where the Jewish population was more concentrated than in the Don, their ranks were engulfed by a vengeful hatred of the Jews. The initiative came from the Cossacks and their regimental officers, although Denikin, a passive anti-Semite, did little to resist it and several of his generals encouraged it. Jews were forced out of Denikin's army and administration. White propaganda portrayed the Bolshevik regime as a Jewish conspiracy and spread the myth that all its major leaders

were Jews apart from Lenin.* As the head of the Red Army, Trotsky (or Bronstein, as he was parenthesized in the White press) was singled out as a monstrous 'Jewish mass-killer' of the Russian people. The Jews were blamed for the murder of the Tsar, for the persecution of the Orthodox Church and for the Red Terror. Now it is true that the Jews were prominent in the Kiev and other city Chekas. But this was used as a pretext to take a bloody revenge against the Jewish population as a whole. As the Chief Rabbi of Moscow once put it, it was the Trotskys who made the revolutions but it was the Bronsteins who paid the bills. Most of the White leaders, including Denikin, took the view that the Jews had brought the pogroms on themselves because of their 'support' for the Bolshevik regime. The whole of the White movement was seized by the idea that the persecution of the Jews was somehow justified as a popular means of counterrevolution. The Russian Rightist Shulgin, a major spokesman on the Jews' collective guilt, later acknowledged that the pogroms were a White revenge for the Red Terror.

'We reacted to the "Yids" just as the Bolsheviks reacted to the

burzhoois.

They shouted,

"Death to the

Burzhoois!"

And we replied, "Death to the Yids!"'40

The first major pogroms were perpetrated by Petliura's Ukrainian nationalist bands in the winter of 1918—19. The partisans of Makhno and Grigoriev also carried out pogroms, as did the Poles in 1920, and some units of the Red Army. In all these pogroms, except those of the Poles (which were racially motivated), anti-Jewish violence was closely associated with the looting and destruction of Jewish property. The Ukrainian peasant soldiers hated the Jews mainly because they were traders, inn-keepers and money-lenders, in short the 'bourgeoisie' of the 'foreign' towns who had always exploited the 'simple villagers' and kept them living in poverty. It was common for pogrom leaders to impose a huge revolutionary tax on the Jews — in the belief that they were fantastically wealthy — and then to kill the hostages taken from them when the taxes were not paid. The Bolsheviks employed the same methods during the Red Terror.

It was also common for the pogrom leaders to license their soldiers to loot Jewish shops and houses, murdering and raping the Jews in the process, and to allow the local Russian population to help themselves to a share of the spoils, under the pretext that the Jews had grown rich from speculating on the economic crisis and that their wealth should be returned to the people. The Bolsheviks called this looting the looters.

The pogroms carried out by Denikin's troops were largely driven by the same simple instinct to rob, rape and kill a Jewish population which was

* The myth gained currency in Western circles. General Holman, for example, the head of the British military mission to Denikin, told a Jewish delegation that of the thirty-six Commissars in Moscow, only Lenin was not a Jew (Shekhtman,

Pogromy,

298).

seen as wealthy, alien and weak. But in a way that was more apparent than in the earlier pogroms they were also motivated by a racial hatred for the Jews and by a hatred of them, in the words of one White officer, as the 'chosen people of the Bolsheviks'. Whole Jewish towns were burned and destroyed on the grounds that they had supported the Reds (was it any wonder that they did?). Red stars were painted on the synagogues.

Jews were taken hostage and shot in reprisal for the Red Terror. Jewish corpses were displayed in the street with a sign marked 'Traitors', or with a Red Star cut into their flesh.41

On seizing a town from the Reds, it was common for the White officers to allow their soldiers two or three days' freedom to rob and kill the Jews at will. This was seen as a reward for the troops and a just retribution for the part played by the Jews in supporting the Reds. There were no recorded cases of a White officer ever halting a pogrom, but several cases where even senior generals, such as Mamontov and Mai-Maevsky, ordered them. One of the worst pogroms took place in Kiev, right under the noses of the White authorities. From I to 5 October the Cossack soldiers went around the city breaking into Jewish homes, demanding money, raping and killing. The officers and local priests urged them on with speeches claiming that 'The Yids kill all our people and support the Bolsheviks.' Even Shulgin, an ardent anti-Semite, was disturbed by the climate of 'medieval terror' in the streets and by the 'terrifying howl' of the 'Yids' at night 'that breaks the heart'. Yet General Dragomirov, who ruled the city, did not order a stop to the pogrom until the 6th, the day after the orgy of killing had finally burned itself out.42

Many pogroms were accompanied by gruesome acts of torture on a par with those of the Red Terror. In the town of Fastov the Cossacks hung their victims from the ceiling, releasing them just before they choked to death: if their relatives, who watched this in terror, could not pay up the money they had demanded, the Cossacks repeated the operation. The Cossacks cut off limbs and noses with their sabres and ripped out babies from their mothers' wombs. They set light to Jewish houses and forced those who tried to escape to turn back into the fire. In some places, such as Chernobyl, the Jews were herded into the synagogue, which was then burned down with them inside. In others, such as Cherkass, they gang-raped hundreds of pre-teen girls. Many of their victims were later found with knife and sabre wounds to their small vaginas. One of the most horrific pogroms took place in the small Podole town of Krivoe Ozero during the final stages of the Whites' retreat in late December. By this stage the White troops had ceased to care about world opinion and, as they contemplated defeat, threw all caution to the winds. The Terek Cossacks tortured and mutilated hundreds of Jews, many of them women and young children. Hundreds of corpses were left out in the snow for the dogs and pigs to eat. In the midst of this macabre scene the Cossack officers held a surreal ball in the town post

office, complete with evening dress and an orchestra, to which they invited the local magistrate and a group of prostitutes they had brought with them from Kherson. While their soldiers went killing Jews for sport, the officers and their

beau monde

drank champagne and danced the night away.43

Thanks to the newly opened archives, we now have a fuller idea of how many Jews were killed by pogroms in the civil war. The precise number will never be known. Even the pogroms by the Whites, which are the best known, raise all sorts of statistical problems; and there were many other pogroms against Jews (by the Ukrainian nationalists, by Makhno's partisans, by the invading Polish forces and by the Reds) whose victims were never counted at all. But one can say with some certainty that the overall number of Jewish murder-victims must have been much higher than the 31,071

burials officially recorded or indeed the estimates of 50,000—60,000 deaths given by scholars in the past. The most important document to emerge from the Russian archives in recent years, a 1920 report of an investigation by the Jewish organizations in Soviet Russia, talks of 'more than 150,000 reported deaths' and up to 300,000 victims, including the wounded and the dead.44

* * * The fleeing thousands of Denikin's regime all piled into Novorossiisk, the main Allied port on the Black Sea, in the hope of being evacuated on an Allied ship. By March 1920, the town was crammed full of desperate refugees. Dignitaries of the old regime slept a dozen to each room. Typhus reaped a dreadful harvest among the hordes of unwashed humanity. Prince E. N. Trubetskoi and Purishkevich died in the awful conditions of Novorossiisk. No one gave any more thought to the idea of fighting the Reds, whose cavalry encircled the town. Seven years of war and revolution had bred in these people a psyche of defeat — and they now thought only of escape. British guns were thrown into the sea. Cossacks shot their horses. Everyone wanted to leave Russia but not everyone could be taken by the Allied ships. Priority was given to the troops, 50,000 of whom were carried off to the Crimea on 27 March. That left 60,000 Whites at the mercy of the Reds. Amidst the final panic to get on board there were ugly scenes: princesses brawled like fish-wives; men and women knelt on the quay and begged the Allied officers to save their lives; some people threw themselves into the sea.45