A People's Tragedy (61 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

From now on it was a question of whether the revolution would start from below or above. The idea of a 'palace coup' had been circulating for some time. Guchkov was at the centre of one such conspiracy. It aimed to seize the imperial train

en route

from Stavka to Tsarskoe Selo and to force the Tsar to abdicate in favour of his son, with the Grand Duke Mikhail, Nicholas's brother, serving as Regent. In this way the conspirators hoped to forestall the social revolution by appointing a new government of confidence.

However, with only limited support from the military, the liberals and the imperial family, they put off the plans for their coup until March 1917 — by which time it was too late. A second conspiracy was meanwhile being hatched by Prince Lvov with the help of the Chief of Staff, General Alexeev. They planned to arrest the Tsarina and compel Nicholas to hand over authority to the Grand Duke Nikolai. Lvov would then be appointed as the Premier of a new government of confidence. Several liberal politicians and generals supported the plan, including Brusilov, who told the Grand Duke: 'If I must choose between the Emperor and Russia, then I march for Russia.' But this plot was also scotched — by the Grand Duke's reluctance to become involved. There were various other conspiracies, some of them originating with the Tsar's distant relatives, to force an abdication in favour of some other Romanov capable of appeasing the Duma. Historians differ widely on these plots, some seeing them as the opening acts of the February Revolution, others as nothing but idle chit-chat. Neither is probably true. For even if the conspirators had been serious in their intentions, and had succeeded in carrying them out, they could hardly have expected to hold on to power for long before they too were swept aside by the revolution on the streets.61

The only plot to succeed was the murder of Rasputin. Several efforts had been made to remove him before. Khvostov had tried to have his former patron murdered after being dismissed as Minister of the Interior in January 1916. Trepov had offered him 200,000

roubles in cash to return to Siberia and keep out of politics. But the Tsarina had foiled both plans and, as a result, Rasputin's prestige at court had only risen further. It was this that had finally persuaded a powerful group of conspirators on the fringes of the court to murder Rasputin. The central figure in this plot was Prince Felix Yusupov, a 29-year-old graduate of Oxford, son of the richest woman in Russia, and, although a homosexual, recently married to the Grand Duchess Irina Alexandrovna, daughter of the Tsar's favourite sister. Two other homosexuals in the Romanov court — the Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, a favourite nephew of the Tsar, and the Grand Duke Nikolai Mikhailovich — were also involved. Rasputin had become increasingly involved with the homosexual circles of the high aristocracy. He liked to 'lie with' men as much as with women. Yusupov had approached him after his wedding in the hope that he might

'cure' him from his sexual 'illness'. But Rasputin had tried to seduce him instead.

Yusupov turned violently against him and, together with the Grand Dukes Dmitry and Nikolai, plotted his downfall. Along with their own homosexual vendetta (and perhaps in order to conceal it) they had grave political concerns which they voiced to the rightwing Duma leader and outspoken critic of Rasputin, V M. Purishkevich, who joined them in their plot. They were outraged by Rasputin's influence on the Tsar and by the rumours that because of this Russia would sign a separate peace with Germany. They pledged to 'eliminate' Rasputin and to confine the Tsarina to a mental institution, naively believing that once the Tsar had been freed of their influence, he would see sense and turn himself into a good constitutional king.

Together the three conspirators planned to lure Rasputin to Yusupov's riverside palace on the pretext of meeting his beautiful wife, the Grand Duchess Irina. There they would kill him with poison and sink his body to the bottom

of the Neva so that he would be counted as missing rather than dead. The plotters were anything but discreet: half the journalists of Petrograd seem to have known all the details of the murder days before it took place. It is frankly a miracle that, despite the plotters' immunity from police investigation, nothing was done to prevent them.

On the fatal day, 16 December, Rasputin was explicitly warned not to go to the Yusupov palace. He seems to have sensed his fate, for he spent most of the day destroying correspondence, depositing money in his daughter's account and praying.

But the worldly attractions of the Grand Duchess Irina were too much for him to resist.

Shortly after midnight he arrived in Yusupov's car smelling of cheap soap, his hair greased down and dressed in his most seductive clothes: black velvet trousers, squeaky leather boots and a white silk shirt with a satin-gold waistband given to him by the Tsarina. Yusupov showed his guest to a basement salon, claiming his wife was still entertaining guests in the main part of the palace and would join them later. Rasputin drank several poisoned glasses of his favourite sweet Madeira and helped himself to one or two cyanide-filled gateaux. But over an hour later neither had taken effect and Yusupov, his patience exhausted, turned to desperate measures. Taking a Browning pistol from his writing desk upstairs, he rejoined the basement party, invited Rasputin to inspect a crystal crucifix standing on a commode, and, as the 'holy man' bent down to do so, shot him in the side. With a wild scream Rasputin fell to the floor. The conspirators presumed he was dead and went off to dispose of his overcoat. But meanwhile he regained consciousness and made his way to a side door that led into a courtyard and out on to the embankment. Purishkevich found him in the courtyard, staggering through the snow towards the outside gate, shouting, 'Felix, Felix, I will tell the Tsarina everything!' Purishkevich fired and missed him twice. But two more shots brought his victim down in a heap and, just to make sure that he was dead, Purishkevich kicked him in the temple. Weighed down with iron chains, Rasputin's corpse was driven to a remote spot of the city and dumped into the Neva, where it was finally washed up on 18

December. For several days thereafter, crowds of women gathered at the spot to collect the 'holy water' from the river sanctified by Rasputin's flesh.62

The news of Rasputin's murder was greeted with joy among aristocratic circles. The Grand Duke Dmitry was given a standing ovation when he appeared in the Mikhailovsky Theatre on the evening of 17 December. The Tsarina's sister, the Grand Duchess Elisaveta, wrote to Yusupov's mother offering prayers of thanks for her 'dear son's patriotic act'. She and fifteen other members of the imperial family pleaded with the Tsar not to punish Dmitry. But Nicholas rejected their appeal, replying that 'No one has the right to engage in murder.'63 Dmitry was exiled to Persia. On special orders from the Tsar, no one was allowed

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

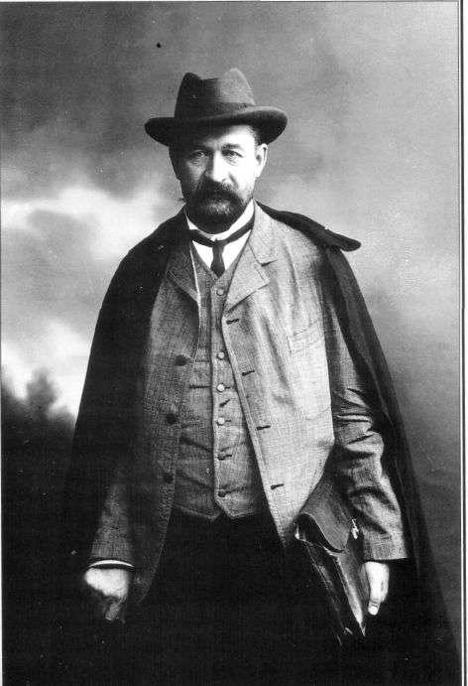

29 General Brusilov in 1917, shortly after his appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Russian army. One of his subordinates described him as 'a man of average height with gentle features and a natural easy-going manner but with such an air of commanding dignity that, when one looks at him, one feels duty-bound to love him and at the same time to fear him'.

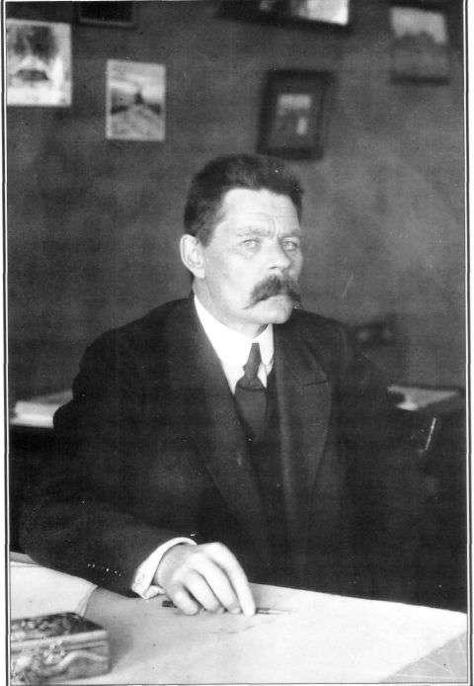

30 Maxim Gorky in 1917. 'It was impossible to argue with Gorky. You couldn't convince him of anything, because he had an astonishing ability: not to listen to what he didn't like, not to respond when a question was asked which he had no answer to' (Nina Berberova). It was no doubt this ability which enabled Gorky to live in Lenin's Russia.

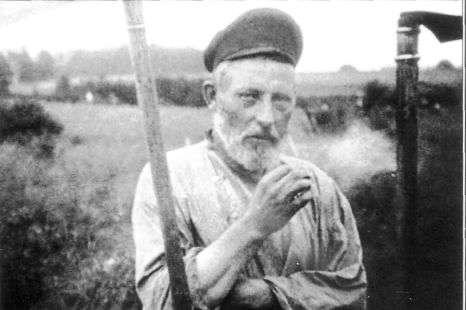

31 Prince G. E. Lvov, democratic Russia's first Prime Minister, in March 1917. During his four months in office Lvov's hair turned white.

32 Sergei Semenov in 1917. The peasant activist was sufficiently well known in his native district of Volokolamsk to warrant this portrait.

33 Dmitry Os'kin

(seated centre)

with the Tula Military Commissariat in 1919. The story of his rise from the peasantry to the senior ranks of the Red Army was later told by Os'kin in two autobiographical volumes of 1926 and 1931. Like Kanatchikov's autobiography, they were part of the Soviet genre of memoirs by the masses.

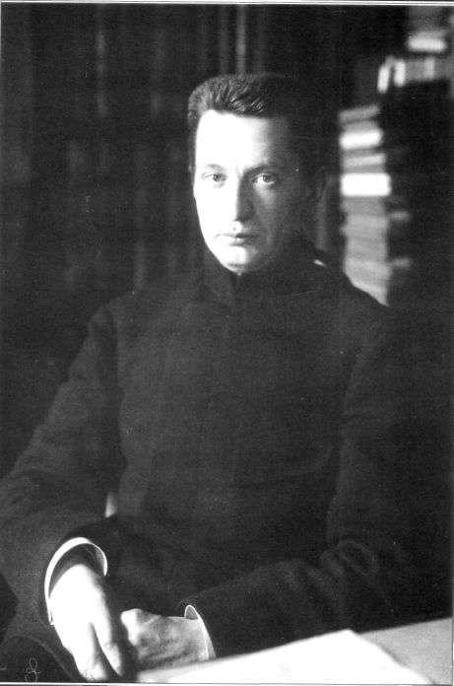

34 Alexander Kerensky in 1917. This was just one of many portraits of Kerensky circulated to the masses in postcard form as part of the cult of his personality.