A Place of My Own (14 page)

Authors: Michael Pollan

Using little more than this pair of thick walls, opened to the landscape on either end, Charlie had found a way to animate the space in the hut and grant his client’s warring wishes for an equally strong sense of refuge and prospect.

On paper, at least. Because right now, any talk about the experience of space in my hut was idle, a matter of hunch and speculation. There was no way I could be sure Charlie’s design worked the way he said it did without actually building it and moving in. This might not have been the case had Charlie designed a more conceptual or literary building—a hut built chiefly out of words or critical theories or signs, the kind that, once worked out on paper, is as good as built (if not better). Just think, this whole project would have been done now, everything but the explanatory texts. I could have slipped back into the warm tub of commentary, and never have had to learn how to cut a bird’s mouth in a rafter or drill a half-inch hole through a boulder in order to pin it to a concrete pier. But no such luck. This particular building was meant to be experienced, not read. Only part of its story can be told on paper; the rest of it would be in wood.

4

Footings

How to get your building down to the ground, the task that now confronted me, has always been a big issue for architects and builders, not only from an engineering perspective—the foundation being the place where a building is most vulnerable to the elements—but philosophically too.

This is perhaps especially true in America. Our architects seem to have devoted an inordinate amount of attention to the relationship of their buildings to the ground—which makes sense, in light of the fact that Americans have always believed, with varying degrees of conviction, that ours is somehow sacred ground, a promised land. The Puritans used to call the New World landscape “God’s second book,” and in the nineteenth century it became the preferred volume of the transcendentalists, who read the land for revelation and moral instruction. It is at any rate the ground of our freedom and, given our varied racial and ethnic composition, the one great thing we hold in common—the thing that makes us all Americans. So it matters how our buildings sit on this ground.

This might explain why, when you compare a great American house such as Monticello to the Palladian models on which it was based, the overriding impression is that Jefferson has put his house on much more sympathetic terms with the ground. Where Palladio’s blocky, classical villas stand somewhat aloof from the earth, Monticello stretches out comfortably over its mountaintop site as if to complete, rather than dominate, it. The horizontal inflection that Jefferson gave to Monticello—this sense that a building should unfold along the ground—proved to be prophetic, for it eventually became one of the hallmarks of American architecture. It finds expression in the floor plans of turn-of-the-century shingle-style houses, which ramble almost like miniature landscapes in imitation of the ground on which they sit, and even in the ground-hugging ranch houses of postwar suburbia.

This same gesture of horizontal expansiveness, behind which surely stand dreams of the frontier and the open road, is what gave even a public work such as the Brooklyn Bridge its powerful sense of horizontal release—“Vaulting the sea,” as Hart Crane wrote of it, and “the prairies’ dreaming sod…” And though considerably darkened, the gesture survives in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in Washington, D.C., perhaps the most stirring meditation yet on the American ground. Along an extended horizontal slit cut into the Mall, the memorial draws us down into the American ground itself, where we come literally face to face with it, to contemplate at once its violation—the slab of granite chronicling the names of the dead it now holds—as well as its abiding power of healing and renewal.

But the greatest, and sunniest, poet of the American ground was Frank Lloyd Wright, who no doubt bore some responsibility for the complicated footings I was about to undertake as the construction of my hut began. Viewed from one perspective, Wright’s lifelong project was to figure out how Americans might best make themselves at home on the land that forms this nation. “I had an idea,” he wrote, “that the planes parallel to the earth in buildings identify themselves with the ground, do most to make the buildings belong to the ground.” That this was something to be wished for went without saying for Wright, who liked to describe himself as “an American, child of the ground and of space.”

“What was the matter with the typical American house?” he asked in a 1954 book called

The Natural House

. “Well just for an honest beginning, it lied about everything.” It had no “sense of space as should belong to a free people” and no “sense of earth.” The first defect he sought to remedy with his open, outward-thrusting floor plans and powerful horizontal lines. The second meant rethinking the foundation, something on which no architect before or since has lavished quite so much attention. (Though with my hut’s footings, Charlie seemed to be mounting a respectable challenge.) Wright held that houses “should begin

on

the ground, not

in

it as they then began, with damp cellars.” He spoke of conventional foundations and basements as if they were unpardonable violations of the sacred ground plane. Along with attics, basements also offended Wright’s sense of democracy, since they implied a social hierarchy. (This was more than just a metaphor: Servants typically occupied one space or the other.) For Wright, the proper space of democracy was horizontal.

Wright devised several alternatives to the traditional foundation, including what he called the “dry wall footing”: essentially a concrete slab at ground level set on a bed of gravel. But even when Wright built more conventional foundations, he would specify that the framing begin on the inside edge of the masonry wall rather than at the outer edge, as is the standard practice. The effect he was after was a kind of plinth, “a projecting base course” of masonry to help the house “

look

as though it began there

at

the ground.” Not that this solution was really all that honest, since the house only

appeared

to rest on the ground; in fact, it often rested on a conventional foundation wall that sliced through the ground to form a cellar. Here where our buildings meet the earth, the ideal and the possible often seem to eye each other tensely.

Wright’s projecting base course of stone also served visually to “weld the structure to the ground”—something, by the way, that at the time only an American was apt to deem desirable. For at the precise historical moment that Wright was taking such pains to wed his buildings to the land, many European modernists were turning their backs on it and dispensing with foundations altogether. Le Corbusier was setting his houses on slender white stilts, or “pilotis,” that stepped gingerly over the ground as if it were unwholesome, touching it in as few places as possible and all but cursing the gravity that made contact with the earth necessary at all. The house of the future was supposed to be as rootless and streamlined as an airplane or ocean liner.

Even when Wright himself went to war against gravity, his purpose was not to escape the ground so much as to honor it. At Fallingwater, in western Pennsylvania, he cantilevered a house out over the waters of the Bear Run not so that it might seem to fly (“A house is not going anywhere,” he once said, in a dig at Le Corbusier’s vehicle worship, “at least not if we can help it”), but as a way to elaborate and extend the stratified rock ledge on which it is literally based. In a sense, Fallingwater is nothing

but

a foundation: The living space is a steel-reinforced concrete extension of the ledge rock that anchors the structure to the ground. Even a house as gravity-defying as this one was still what Wright said all American houses should be: “a sympathetic feature of the ground” expressing its “kinship to the terrain.”

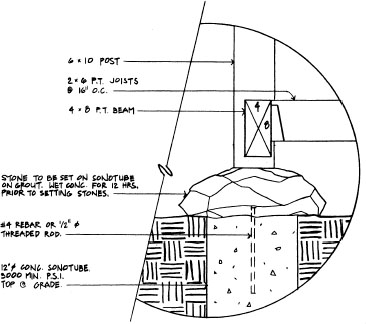

It was ideas such as these that stood behind Charlie’s design for the footings of my hut, a sketch of which arrived in the mail in early October:

This somewhat daunting construction drawing made at least two things plain: A building’s relationship to the ground was a more complicated matter than an architect might want it to appear, and the outward impression and the actual engineering of that relationship were two entirely different matters.

The impression Charlie sought to create with our rock footings (which he soon took to calling the building’s “feet”) was of an unusually comfortable, almost relaxed relationship between the hut and the ground. (In his original concept, you will recall, the building’s relationship to the ground was

so

relaxed that I was going to need a house jack to square it up from time to time.) The four boulders on which the building sat (or at least appeared to sit) implied even more than a “kinship with the terrain”; they suggested the hut was in some sense part and parcel of its site.

Charlie’s objection to standard concrete piers was that they would have pierced the ground; like Wright, he felt the building should sit on the ground plane, not in it. Unlike Wright, however, he wanted his building to rest very lightly on the ground—hence the four discrete rocks instead of a continuous masonry foundation along the building’s perimeter. Nothing should staunch the flow of space coming down the hillside and through the building.

Though Charlie is not one to clothe his design choices in philosophical language or otherwise make large claims for what he does, his footing detail does imply a certain attitude toward the ground, an idea about nature and place. As he explained it to me when I expressed reservations about the footing detail, setting the building on rocks found on the site was a way “to incorporate something of the ‘here’ of this place into the design of the building.” He reminded me of the etching Marc-Antoine Laugier used to depict the birth of architecture, the four living trees in a forest enlisted to form the four posts of his primitive hut. “Rocks are what your site is about,” Charlie said. “Concrete would register as foreign matter here, something citified and imported. This is obviously not a primitive or vernacular building, but that doesn’t mean it can’t meet its place halfway, that there can’t be some give and take.”

Looked at from this perspective, any building represents a meeting place of the local landscape and the wider world, of what is given “Here” and what’s been brought in from “There.” The Here in this case is of course the site, but the site defined broadly enough to take in not only the sunlight and character of the ground, the climate and flora and slope, but also the local culture as it is reflected in the landscape—in the arrangements of field and forest and in the materials and styles commonly used to build “around here.” Conceivably, a building could be based entirely on such local elements, but this happens more seldom than we think: Even a structure as seemingly indigenous as a log cabin built with local timber is based on an idea and a set of techniques imported in the eighteenth century from Scandinavia. Backwoods survivalist types living “off the grid,” as they like to say, may flatter themselves about their independence, but in fact it is only the beavers and groundhogs who truly build locally, completely outside the influence of culture and history, beyond the long reach of There.

And There, of course, is just another way of saying the broader culture and economy, which in our time has become international. The term takes in everything from the prevailing styles of architecture and the state of technology to the various images and ideas afloat in the general culture, as well as such mundane things as the prime rate and the price of materials, labor, and energy. In fact a whole set of values can be grouped under the heading of “There,” and these can be juxtaposed with a parallel set of values that fit under the rubric “Here”:

THERE | | HERE |

Universal | | Particular |

Internationalism | | Regionalism |

Progress | | Tradition |

Classical | | Vernacular |

Idea | | Fact |

Information | | Experience |

Space | | Place |

Mobility | | Stability |

Palladio | | Jefferson |

Jefferson | | Wright |

Abstract | | Concrete |

Concrete | | Rock |

The juxtapositions can be piled up endlessly, and though matters soon get complicated (look what happens to concrete, or to Jefferson and Wright), they can still serve as a useful shorthand for two distinct ways of looking at, or organizing, the world.

The tension between the two terms is nothing new, of course. Thomas Jefferson was dealing with this when he imported Palladianism from Europe and gave it an American inflection; Monticello represents a novel synthesis of There and Here, of classicism and the American ground. (For Wright’s taste and time, however, Jefferson was still too much the classicist, which suggests that Here and There are strictly relative.) In our own time, the balance between the two terms has been steadily tilting toward the There end of the scale. There are some powerful abstractions on the side of There, and in the last century or so these have tended to run over the local landscape. The force and logic of these abstractions are what have helped farmland to give way to tract housing, city neighborhoods to ambitious schemes of “urban renewal,” and regional architecture to an “international style” that for a while elevated the principle of There—of universal culture—to a utopian program and moral precept. Modernism has always regarded Here as an anachronism, an impediment to progress. This might explain why so many of its houses walked the earth on white stilts, looking as though they wanted to get off, to escape the messy particularities of place for the streamlined abstraction of space.