A Place of My Own (21 page)

Authors: Michael Pollan

A few steps from the building sits a large, low boulder Joe often repaired to when he needed to study the plans closely or work through a geometry problem, and now he invited me to join him on his rock for a serious head-scratch. “Didn’t I say we’d used up too much plumb and level on those front posts?” Joe said, straining to lighten a situation he clearly regarded as grim. He was referring to our relative good fortune in raising the front corner posts and framing the lower portion of the floor. Time and time again the little bubble in the level’s window had come to rest dead center in its tube of liquid, an event I learned to await nervously and greet with relief. I’d come to think of the little bubble as a stand-in for people, for our comfortableness in space; level and plumb settled the bubble, stilled its jitteriness, in the same way they settled us, making us feel more at home on the uneven earth.

Joe would often talk about plumb and level and square—trueness—as if they were mysterious properties of the universe, something like luck, or karma, and always in short and unpredictable supply. A surplus one week was liable to lead to a shortfall the next. “We were bound to run out sooner or later, but this, Mike, is grave.” I knew, at least in an intellectual way, that squareness was an important desideratum in a building, but part of me still wasn’t sure why it was

such

a big deal. If the problem wasn’t evident to the eye, then how much could a few degrees off ninety really matter? Why should builders make such a fetish of right angles—of something as old-fashioned as “rectitude”? I mentioned to Joe there were architects around, called deconstructivists, who maintained that Euclidean geometry was obsolete. They designed spaces that were deliberately out of plumb, square, and sometimes even level, spaces that set out purposefully to confound the level’s little bubble, and in turn our conventional notions of comfort. “Straight,” “level,” “plumb,” “true”: in the postmodern lexicon, these terms are…well, square. So why couldn’t our building afford an acute angle or two? Joe cocked one eye and looked at me darkly, an expression that made plain he regarded my hopeful stab at non-Euclidean geometry as an instance not of apostasy but madness.

“Mike, you don’t even want to know all the problems that a building this far out of square is going to have. Trust me—it is your worst nightmare.”

Sitting there on Joe’s rock, pondering the mystery, we were able to come up with two plausible explanations for what had happened. Both were equally depressing, though in very different ways. Either it was human error in the placement of one of the front posts on its rock, or an act of God involving movement of the rear footings. Earlier that spring we had observed a tremendous amount of groundwater coming through the site (something a fêng shui doctor would doubtless have foreseen). The ground was saturated in March, and as the earth around our footings thawed, we could actually hear gurgling sounds deep underfoot, as if a stream were passing directly beneath us. Could the force of the groundwater actually have moved a four-foot concrete pier? Joe claimed it was possible.

I personally found it difficult to accept that an act of God, or nature, was responsible for throwing our building out of square. To endorse this view might exonerate our workmanship, but it raised too many uncomfortable questions about foundations—about the dependability of the frost line and the very possibility of ever safely grounding a building. I was more inclined to think human error was the cause—what Joe called an “act of idiocy,” as opposed to an act of God—and I worked out a scenario in which a seemingly trivial bit of carelessness in the placement of one of our little pressure-treated post “shoes” could have caused the calamity without our realizing it. I may have been more right than I knew when I said they were the building’s Achilles’ heel.

Thinking back on it, I did have this vagueish memory involving the shoe under the outside northwest post—about how it might have sat a little funny when we put it down on the rock that final time, as if it had been turned around or flipped over. If so, then the entire northwest corner of the building was twisted slightly in space, which would be enough to account for the discrepancies we’d found in the rear posts.

The error, this simple, stupid, unconscious, un-undoable error, haunts my building even now. For although Joe and I were able with great difficulty to make some adjustments in the placement of the rear posts (by shifting where they fell on their rocks, and rotating one of the rocks on its pier), we were never able to entirely rectify the problem—and therefore, the building, which we estimate to be approximately two degrees out of square. As a result, the front wall of my building is slightly more than an inch wider than the back.

Not that it’s anything anyone’s ever going to notice. At the casual, phenomenological level of everyday life, a building a couple degrees out of square is no big deal. Unfortunately for me, that is not the level at which I elected to have this experience. And at the considerably less forgiving level of experience where rafters have to get cut and desktops scribed, it has been exactly what Joe promised it would be: a nightmare. The whole of the rest of the project has been a seminar in the consummate beauty, if not the transcendental necessity, of square, something I now look back upon wistfully as a lapsed state of architectural grace. Cast out of square, I’ve learned more than I care to know about the stern and unforgiving syntax of framing, in which any departure from geometrical rectitude ramifies through the world of the structure without end, a dilating, unstoppable stain, an ineradicable corruption. Every step taken since the flip of that shoe has been dogged by those two degrees: Every pair of rafters has had to be cut to a slightly different length; every floorboard and windowsill, every piece of trim and flashing, has an eighty-eight-degree angle somewhere in it, the indelible watermark of our stupidity. Even now, years later, consequences rear up in reminder. When I want to add another shelf to hold my books, I’m quickly reminded that no straightforward rectangle will do. No, I must lay out and cut, then sand and finish and dismayingly behold, the subtlest of trapezoids, a precise off-key echo of the building as a whole. It has been a most exquisite form of penance.

But if framing had given the building its darkest day, cleaving it once and for all from geometrical perfection, it also gave us a few of its brightest: banner days of swift progress and high spirits in which the building literally rose up and took shape before our eyes, almost as if in time-lapse. By Memorial Day, all eight corner posts were standing, along with the upper and lower beams connecting them front to back, and the entire subfloor had been nailed down—faintly trapezoidal, it’s true, but I’m proud to say dead-on, bubble-stillingly level.

The weather that June was particularly fine, and many hands mustered. Especially on the Saturday that spring turned into summer, when Judith and I threw a barbecue for a dozen or so friends that turned the following morning into an impromptu frame-raising party. Those who weren’t at ease swinging hammers stood around the site and gabbed, watching the kids and shooting video of the doings above, while a handful of us climbed up into the frame, under a fine canopy of new leaves, and nailed into place the sweet-smelling planks of freshly cut fir passed up from below. Isaac was two months shy of his first birthday, and I have a snapshot Judith took of the two of us on the site that splendid afternoon. I’m ferrying lumber to the framers from a stockpile in the barn, all the while carrying Isaac in a pack on my back; OSHA would not have approved. Isaac’s got nothing but a diaper on, and his tiny pink hand is reaching up to steady the two-by-six balanced on my shoulder.

Charlie was also on hand, and Joe was due but running more than his usual couple of hours behind schedule. (The man might be a master of space, but time is another matter altogether.) On this occasion, though, there may have been extenuating circumstances. For this was to be Joe and Charlie’s first face-to-face, a prospect neither of them relished.

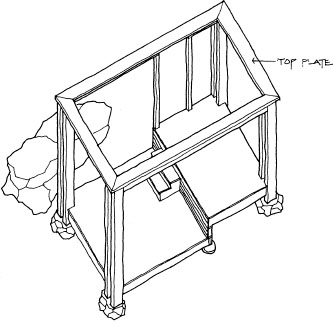

Before Joe arrived we worked on the foot-wide Doug fir plank that Charlie had spec’d to span the tops of the corners posts and tie all four walls together. Like a great many components of the building’s frame, this one performed several distinct functions at once, some structural, others formal or ornamental. Structurally, the plank functions as the top plate of the walls, stiffening the frame all around while providing a header for the windows and a seat for the rafters. Inside, the same member serves as the topmost bookshelf, articulating the depth and height of the thick walls that run the length of the building’s long sides. Then, at either end of the building, three inches of the plate extend through the wall, jutting out to form a ledge, or lip, on the front and rear elevations, which crowns the corner posts much like a slender cornice. This is its formal role: by establishing a strong, crisp line across the face of the building and defining the base of the pediment, the plank (in combination with the visor in front) gives all the columns something to “die into,” thereby resolving the problem of how to terminate the two inner posts. Charlie prepared an axonometric drawing to show us how the cornice plate was supposed to work:

The cornice is exactly the sort of elegantly economical detail I might never have appreciated had I not worked on it directly. With the cornice Charlie had pushed the possibilities of “articulated” structure as far as he could, enlisting the building’s frame in the structure of its thick walls and then bringing that interior element out into the design of the exterior elevation. (Though I hasten to add that this is strictly an architect’s concept of economy: Since the detail was so important, Charlie had insisted we build the cornice using the clearest, and very dearest, grade of fir.)

As we waited for Joe to show up, Charlie climbed up into the frame to help me lay out our four planks, a procedure that very quickly brought him up to speed on the whole squareness issue. He was doing his best to be nonchalant about it too, though I could see that so messy and steep a declension from the structure he had drawn clearly disturbed him. From an architect’s point of view, our two-degree lapse outraged acceptable practice, and I was grateful to Charlie for not giving me too hard a time about it. But that did not mean he was prepared to let our mistake compromise the appearance of his building, no matter what the cost in effort or aggravation.

It had been Joe’s and my plan all along to block the spread of out-of-squareness right here, at the plate. By cutting the planks square and then “floating” that perfect rectangle above the imperfect rectangle of our frame, we would “lose” the problem at the top of the walls and thereby preserve our roof from the spread of geometrical imperfection. The advantage of making the cornice square is that it would give us a perfectly symmetrical base on which to erect our two gables, vastly simplifying the job of cutting rafters and framing the roof. But Charlie contended that to do this would be a big mistake. The slight discrepancy between the plane of the walls and the plate above them would “wreck” the cornice, he explained, since its depth (and therefore the conspicuous line of shadow it cast) would vary at every point along its length. “It’s really,

really

going to bother you,” Charlie said. By “you” he of course meant himself; Charlie had become fully as proprietary about the building as Joe and I were. I couldn’t decide whether it was a good or a bad thing that Joe wasn’t around to argue the point with him.

Charlie wanted us to cut the plates to match the imperfect frame, thereby pushing the squareness problem up into the rafters, where it would be more or less out of view. “I’m not saying it won’t be a headache,” he acknowledged. “You’re going to be cutting every pair of rafters individually, each to a slightly different length. But then—I promise—it’ll be over, the problem won’t go any further than that.” How could it? The

building

didn’t go any further than that. But it seemed to me that if Charlie felt this strongly about the cornice detail, it was probably wise to go along.

Charlie and I were already nailing down the untrued cornice planks when Joe finally appeared, trudging up the hill to the site elaborately festooned with power tools and extension cords. He had on red, white, and blue suspenders, circa 1969, and a pair of trousers, which immediately set him apart from the weekend carpenters on hand in our shorts. Charlie and I came down off our ladders for the introductions, and the two of them shook hands—carefully. Charlie launched an initial foray into geniality, complimenting Joe on his craftsmanship, but when the gesture wasn’t reciprocated, he promptly chomped a few nails between his teeth, climbed back up his ladder, and returned to the plank he’d been spiking. It was not a comfortable moment, and the news I had for Joe about the planks did not promise to improve it. I remember thinking:

Men!

When I told Joe how we’d decided to handle the cornice plate, he gave a shrug of what I knew to be feigned indifference: the two of us had been going back and forth about whether or not to square these planks for weeks as we framed up the side walls, so I knew he had strong feelings on the subject. “Mike, it’s your building,” he now mumbled, by which I was meant to understand,

and not Charlie’s

. Then he looked up at the architect, swinging his hammer on top of the wall, and invited him to come back and help out again the following weekend, and all the weekends after that, when we’d

still

be custom-cutting rafters. “Because framing this roof is shaping up as a

real

good time!”