A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (35 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

One week after the Kurdish refugees had begun pouring into Turkey. the sanctions bill, which kept the name "Prevention of Genocide Act," was introduced on the Senate floor. It passed the Senate the next day on a unanimous voice vote. Because senators did not hold a roll-call vote, they were not on the written record as having supported the bill, which would subsequently enable them to squirm more easily out of their commitments. On September 9, 1988, though, Galbraith noticed only the remarkable tally. It looked to him and most observers as if, to paraphrase Holocaust survivor Primo Levi, it was the good fortune of Iraqi Kurds to be attacked with chemical weapons. The bill needed only to clear the House before it became law.

A "Reorganization of the Urban Situation"

If Galbraith was relieved by the vote, the Reagan administration was alarmed. U.S. officials knew of Hussein's general designs. The State Department's cable traffic from the first week of September continued to report on Iraq's campaign of destruction against the Kurds. On September 2, 1988, a full week ahead of the passage of the Prevention of Genocide Act in the Senate, Morton Abramowitz, the former U.S. ambassador to Thailand who was then assistant secretary of state for intelligence and research, sent a top-secret memo to the secretary of state entitled, "Swan Song for Iraq's Kurds?" Abramowitz cited evidence that Iraq had used chemical weapons against the Kurds on August 25, writing, "Now, with cease-fire [with Iran], government forces appear ready to settle Kurdish dissidents once and for all .... Baghdad is likely to feel little restraint in using chemical weapons against the rebels and against villages that continue to support them."Abramowitz acknowledged that "the bulk" of Kurdish villages were vulnerable to attack." Hussein's forces would consider Kurdish civilians and soldiers alike fair game.

But this made little difference in a State Department and White House determined to avoid criticizing Iraq. A September 3 cable from the State Department to the U.S. embassy in Baghdad urged U.S. officials to stress to Hussein's regime that the United States understood the Kurds had aligned with Iran and that the problem was a "historical one." U.S. diplomats were told to explain that they had "reserve[d] comment" until they had been able to take Baghdad's view "fully into account"" Still, the conduct of Iraq's campaign was causing international outcry that was becoming embarrassing for the United States. In consultation with Iraqi foreign ministry undersecretary Nizar Hamdoon the following day, Ambassador April Glaspie warned that Iraq had "a major public relation problem." She noted that the lead story on the BBC that morning had been the gas attacks and said,"If chemical warfare is not being used and if Kurds are not herded into WWII concentration camps," then Iraq should permit independent observers access to Kurdish territory. Hamdoon denied chemical weapons use but said the access she requested was "impossible" just then. Besides, the fighting would be over "in a few days"The embassy "comment" on the meeting was that "it has been clear for many days that Saddam has taken the decision to do whatever the army believes necessary to fully pacify the north.""

In public, State Department officials betrayed little of this behind-thescenes grasp of Iraq's agenda. Picking up on wire reports of gas attacks that started running August 10, journalists had begun pressing State Department spokespersons for comment on the attacks on August 25. Day after day spokesperson Phyllis Oakley said she had "nothing" to substantiate the reports. Her colleague Charles Redman said on September 6 that he could not confirm the news stories. Sensing the reporters' exasperation, Redman did add a hypothetical condemnation. "If they were true, of course we would strongly condemn the use of chemical weapons, as we have in the past," he said. "The use of chemical weapons is deplorable. It's barbaric""

U.S. officials reluctant to criticize Iraq again took refuge in the absence of perfect information. They noted that the reports from the Turkish border were not unanimous. Bernard Benedetti, a doctor with Medecins du Monde, had found no chemical weapons cases. "That's a false problem," he told the Washington Post, referring to chemical weapons. "The refugees here are suffering from diarrhea and skin rash which are spreading because of overcrowding and unsanitary conditions " " Turkey likewise insisted that forty doctors and 205 other health personnel had found no proof of the atrocities. One Turkish doctor told the NewY)rk Tinies that the blisters on the face of a three-year-old Kurdish boy came from "malnutrition" and "poor cleanliness"" But neither source was reliable. Physicians with the international aid agencies had no expertise on diagnosing the side effects of exposure to chemical weapons, and Turkey got most of its oil from Iraq and conducted $2.4 billion in annual trade with its neighbor.' It also frequently partnered with Iraq to suppress Kurdish rebels.

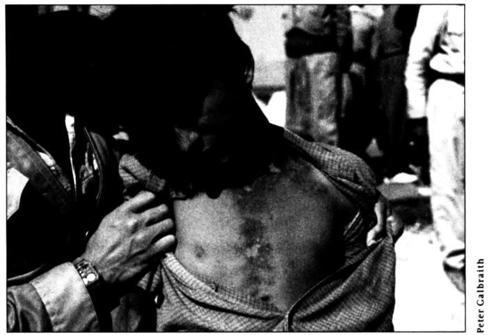

Shaken refugees in Turkey found their claims rudely challenged. Clyde Haberman of the New York Tirnes described a "reluctant subject," thirteenyear-old Bashir Semsettin, who after suffering a gas attack and landing in Turkey found "his thin body pulled and prodded like an exhibit ... for the benefit of curious visitors." Bashir's chest and upper back were scarred in a "marbled pattern" of burns, with streaks of dark brown juxtaposed beside large patches of pink. While he was pent up in a Turkish medical tent, a Turkish MP arrived with an entourage of assistants and began poking at Bashir's wounds.

"What are these?" the lawmaker asked.

"Burns," replied the Turkish government physician.

Bashir Semsettin, Kurdish survivor of an Iraqi chemical attack.

"What sort of burns?" the MP pressed.

"Who can say?" the physician answered. "I know these are firstdegree burns from a heat source other than flames," he said. "If they were flames, his hair and eyebrows would also be burned. But I can't say if they're from chemicals.They can be from anything.""

The Reagan administration had been conciliatory toward Iraq for years, always preferring double condemnations of Iraq and Iran and requests for additional fact finding.Yet at the time of the massive Kurdish flight in September, the State Department consensus at last began to crack. The State Department's Bureau for Near Eastern Affairs (NEA), run by Richard Murphy, and the Bureau for Intelligence and Research (INR), run by Abramowitz, took different positions. Within several days of the launching of the final Anfal, INR intercepted Iraqi military communications in which the Iraqis themselves confirmed that they were using chemical weapons against the Kurds. A pair of U.S. embassy officials also spent two days conducting interviews with refugees from twenty-eight villages at the Turkish border. The refugees and the intercepts together left little doubt. But Murphy's bureau, which managed the U.S. political relationship with Iraq, remained unconvinced. Murphy may have mistakenly trusted Iraqi denials of responsibility and thus discounted the overwhelming evidence of Iraqi poison attacks. Or he may have willfully cast doubt on the information because he believed the U.S.-Iraq relationship would be harmed if the United States condemned the gassing. "I certainly don't recall deliberate slanting," Murphy says today. "I think that we did what we are supposed to do with intelligence: We challenged it. We said, `Where did you get it?'; `Who were your sources?'; `How do you know you can trust those sources?"' Whatever the bureau's motives, NEA officials contested INR's findings long after the intelligence officers found the evidence of Iraqi responsibility overwhelming.

After nearly two weeks of heated internal debate, the INR view finally prevailed. It had been nearly eighteen months since al-Majid had begun his vicious counter-insurgency campaign. The United States had long known about the destruction of Kurdish villages and disappearances of Kurdish men. But only after the high-profile refugee flight and the deluge of press inquiries did Secretary of State Shultz decide to speak out. "As a result of our evaluation of the situation," spokesman Redman declared authoritatively on September 8, 1988, "the United States government is convinced that Iraq has used chemical weapons in its military campaign against Kurdish guerrillas.""' When he was challenged to account for why the United States had been so reticent about responding to chemical weapons attacks in the past, Redman noted, "All of these things have a way of evolving. And it's simply a matter of the course of events.""" Another official cited the Department's fear of crying wolf as it had done in the early 1980s when it charged that Soviet-backed forces had employed chemical weapons against guerrillas in Laos and Cambodia. U.S. officials had been embarrassed by the findings of independent biologists who said that the "yellow rain" that the United States had blamed on trichothecene mycotoxins was in fact pollen-laden droppings from bee swarms."

On the same day Secretary Shultz confirmed Iraqi chemical use, he raised the matter with Saddoun Hammadi, Iraqi minister of state for foreign affairs, delivering what Murphy and others present described as a fifty-minute harangue. Hammadi denied the U.S. charge three times during the meeting, calling the allegations "absolutely baseless."" But he said Iraq had a responsibility to "preserve itself, not be cut to pieces."The Iraqi perspective, like that of most perpetrators, was grounded in a belief that the collective could be punished for individual acts of rebellion. Baghdad had to "deal with traitors." Shultz suggested they be arrested and tried, not gassed .13 Britain, which up to this point had been mute, quickly followed the U.S. lead with a similar statement.

Iraqi Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz, too, vehemently denied allegations of wrongdoing. Aziz did not dispute that the Iraqi government was relocating a number of Kurds who lived near the Iranian border. But sounding an awful lot like Talaat Pasha, the Ottoman minister of the interior in 1915, he stressed, "This is not a deportation of people, this is a reorganization of the urban situation""'

Iraq's defense minister, General Adrian Khairallah, was more revealing in his statements. Iraq was entitled to defend itself with "whatever means is available." When confronting "one who wants to kill you at the heart of your land," he asked, "will you throw roses on him and flowers?" Combatants and civilians looked alike: "They all wear the Kurdish costume, and so you can't distinguish between one who carries a weapon and one who does not."'5

The Iraqi regime was watching Washington carefully. Indeed, the September 9 Senate passage of the sanctions bill and the Shultz condemnation gave rise to the largest anti-American demonstration in Baghdad in twenty years. Some 18,000 Iraqis turned out in a rigged "popular" protest. The Iraqi media inflated the figure to 250,000, and said a "large group" of Kurds also attended. Each evening Iraq's state-run television broadcast clips of Vietnamese civilians who had been burned by U.S. napalm bombs, as well as images of Japanese victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki."' Baghdad media derided the sanctions as the handiwork of "Zionists" and other "potentates of imperialism and racism." The Reagan administration saw Iraq's propaganda as a testament to the peril to U.S.-Iraqi relations; Galbraith considered it proof of the potential for American influence."

Iraq had recently spent vast energy and resources fending off criticisms in Geneva, New York, and Washington. In 1985 the Iraqi embassy in Washington had hired a public relations firm, Edward J.Van Kloberg and Associates, to help it renovate its reputation. Ambassador Nizar Hamdoon agreed to pay the firm $1,000 for "every interview with [a] distinguished American newspaper" that could be arranged. The company had organized television interviews and succeeded in placing articles favorable to Iraq in the Washington Post, New York Times, Washington Times, and Wall Street Journal."" Desperate for foreign investment and reconstructive aid, Iraq was promoting the image of a "new Iraq." It cared about the outside world's opinion.

Iraq's ambassador to the United States, Abdul-Amir All al-Anbari invited any journalist to northern Iraq "to see for himself the truth."This was a typical delay tactic: Visitors are promised access but then denied it once the act of granting permission has deflated outrage. In some instances, after endless delays, independent observers are allowed to visit the prohibited territory, but then, like Becker in Cambodia, they are trailed at all times by a "security escort" handpicked by the regime. Iraqi officials who offered access to an impartial international inquiry quickly added that such a mission would have to be delayed until "active military operations" in northern Iraq had been concluded."' In late September twenty-four Western journalists were let in, but only on a carefully supervised government helicopter tour. The trip proved embarrassing for Baghdad: Iraq airlifted journalists to an outpost on the Iraq-Turkey border to witness the return of 1,000 refugees. But the Kurds failed to show, and the journalists spotted an Iraqi truck whose driver and passengers were hidden behind gas masks."'

Unhappy with Shultz's September 8 condemnation, U.S. Middle East specialists tried to "walk the Secretary back" to a more conciliatory posi- tion.12 When Ambassador Glaspie met again September 10 with Hamdoon, she acknowledged that in 1977 in Cairo she herself had seen people with burns and nausea from mere tear gas. In a secret cable back to Washington, the embassy credited Iraq for the "remarkably moderate and mollifying mode of its presentation" and an "atypical willingness to gulp down their pride and give us assurances even after we publicly announced our certainty of their culpability." "'