A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (60 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

Despite this matter-of-fact assessment, Christopher remained reluctant to speak the obvious truth.When he issued his guidance, on May 24, fully a month after Human Rights Watch had identified the killings as "genocide," Christopher's instructions were hopelessly muddied:

The delegation .s authorized to agree to a resolution that states that "acts of genocide" have occurred in Rwanda or that "genocide has occurred in Rwanda" Other formulations that suggest that some, but not all of the killings in Rwanda are genocide ... e.g. "genocide is taking place in Rwanda"-are authorized. Delegation is not authorized to agree to the characterization of any specific incident as genocide or to agree to any formulation that indicates that all killings in Rwanda are genocide."'

Notably, Christopher confined permission to acknowledge full-fledged genocide to the upcoming session of the Human Rights Commission.

Outside that venue State Department officials were authorized to state publicly only that "acts of genocide" had occurred.

State Department spokesperson Shelly returned to the podium on June 10, 1994. Challenged by Reuters correspondent Alan Elsner, she attempted to follow the secretary's guidance:

Elsner: How would you describe the events taking place in Rwanda?

Shelly: Based on the evidence we have seen from observations on the ground, we have every reason to believe that acts of genocide have occurred in Rwanda.

Elsner: What's the difference between "acts of genocide" and "genocide"?

Shelly: Well, I think the-as you know, there's a legal definition of this.... Clearly not all of the killings that have taken place in Rwanda are killings to which you might apply that label.... But as to the distinctions between the words, we're trying to call what we have seen so far as best as we can; and based, again, on the evidence, we have every reason to believe that acts of genocide have occurred.

Elsner: How many acts of genocide does it take to make genocide? Shelly: Alan, that's just not a question that I'm in a position to answer.62

The same day, in Istanbul, Warren Christopher, by then under severe internal and external pressure to come clean, relented: "If there is any particular magic in calling it genocide, I have no hesitancy in saying that"`'`

Response

"Not Even a Sideshow"

Once the Americans had been evacuated from Rwanda, the massacres there largely dropped off the radar of most senior Clinton administration officials. In the situation room on the seventh floor of the State Department, a map of Rwanda had been hurriedly pinned to the wall when Habyarimana's plane was shot down, and eight banks of phones had rung off the hook. Now, with U.S. citizens safely home, the State Department chaired a daily interagency meeting, often by teleconference, designed to coordinate midlevel diplomatic and humanitarian responses. Cabinet-level officials focused on crises elsewhere. National Security Adviser Anthony Lake, who happened to know Africa, recalls, "I was obsessed with Haiti and Bosnia during that period, so Rwanda was, in journalist William Shawcross's words, a `sideshow,' but not even a sideshow-a no-show." At the NSC the person who managed Rwanda policy was not Lake but Richard Clarke, who oversaw peacekeeping policy and for whom the news from Rwanda only confirmed a deep skepticism about the viability of UN deployments. Clarke believed that another UN failure could doom relations between Congress and the United Nations. He also sought to shield the president from congressional and public criticism. Donald Steinberg managed the Africa portfolio at the NSC and tried to look out for the dying Rwandans, but he was not an experienced infighter, and, colleagues say, he "never won a single argument" with Clarke.

The American' who wanted the United States to do the most were those who knew Rwanda best. Joyce Leader, Rawson's deputy in Rwanda, had been the one to lock the doors to the U.S. embassy for the final time.

When she returned to Washington, she was given a small room in a back office and told to prepare the State Department's daily Rwanda summaries, drawing on press and U.S. intelligence reports. Incredibly, despite her expertise and her contacts in Rwanda, she was rarely consulted and was instructed not to deal directly with her sources in Kigali. Once an NSC staffer did call to ask, "Short of sending in the troops, what is to be done?" Leader's response, unwelcome, was "Send in the troops"

Throughout the U.S. government, Africa specialists had the least clout of all regional specialists and the smallest chance of affecting policy outcomes. In contrast, those with the most pull in the bureaucracy had never visited Rwanda or met any Rwandans.

The dearth of country or regional expertise in the senior circles of government not only reduces the capacity of officers to assess the "news" but also increases the likelihood-a dynamic identified by Lake in his 1971 Foreign Policy article-that killings will become abstractions. "Ethnic bloodshed" in Africa was thought to be regrettable but not particularly unusual. U.S. officials spoke analytically of "national interests" or even "humanitarian consequences" without appearing gripped by the human stakes.

As it happened, when the crisis began President Clinton himself had a coincidental and personal connection with the country. At a coffee at the White House in December 1993 Clinton had met Monique Mujawamariya, the Rwandan human rights activist. He had been struck by the courage of a woman who still bore facial scars from an automobile accident that had been arranged to curb her dissent. Clinton had singled her out, saying, "Your courage is an inspiration to all of us.."" On April 8, two days after the onset of the killing, the Washington Post published a letter that Alison Des Forges had sent to Human Rights Watch after Mujawamariya had hung up the phone to face her fate. "I believe Monique was killed at 6:30 this morning," Des Forges had written. "I have virtually no hope that she is still alive, but will continue to try for more information. In the meantime... please inform everyone who will care."" Word of Mujawamariya's disappearance got the president's attention, and he inquired about her whereabouts repeatedly. "I can't tell you how much time we spent trying to find Monique," one U.S. official remembers. "Sometimes it felt as though she was the only Rwandan in danger." Miraculously, Mujawamariya had not been killed; she had hidden in the rafters of her home after hanging up with Des Forges and eventually managed to talk and bribe her way to safety. She was evacuated to Belgium, and on April 18 she joined Des Forges in the United States, where the pair began lobbying the Clinton administration on behalf of those left behind.With Mujawamariya's rescue, reported in detail in the Post and the New York Tinies, the president apparently lost his personal interest in events in Rwanda.

It is shocking to note that during the entire three months of the genocide, Clinton never assembled his top policy advisers to discuss the killings. Anthony Lake likewise never gathered the "principals"-the cabinet-level members of the foreign policy team. Rwanda was never thought to warrant its own top-level meeting. When the subject came up, it did so along with, and subordinate to, discussions of Somalia, Haiti, and Bosnia. Whereas these crises involved U.S. personnel and stirred some public interest, Rwanda generated no sense of urgency and could safely be avoided by Clinton at no political cost.

The UN Withdrawal

When the killing had begun, Romeo Dallaire expected and appealed for reinforcements. W ithin hours, he had cabled UN headquarters in New York: "Give me the means and I can do more" He was sending peacekeepers on rescue missions around the city, and he felt it was essential to increase the size and improve the quality of the UN's presence. But the United States opposed the idea of sending reinforcements, no matter where they were from. The fear, articulated mainly at the Pentagon, was that what would start as a small engagement by foreign troops would end as a large and costly one by Americans. This was the lesson of Somalia, where U.S. troops had gotten into trouble after returning to bail out the beleaguered Pakistanis. The logical outgrowth of this fear was an effort to steer clear of Rwanda entirely and he sure others did the same. Only by yanking Dallaire's entire peacekeeping force could the United States protect itself from involvement down the road. One senior U.S. official remembers,

When the reports of the deaths of the ten Belgians came in, it was clear that it was Somalia redux, and the sense was that there would be an expectation everywhere that the U.S. would get involved. We thought leaving the peacekeepers in Rwanda and having them confront the violence would take us where we'd been before. It was a foregone conclusion that the United States wouldn't intervene and that the concept of UN peacekeeping could not be sacrificed again.

"A foregone conclusion." What is most remarkable about the American response to the Rwandan genocide is not so much the absence of U.S. military action as that during the entire genocide the possibility of U.S. military intervention was never even debated. Indeed, the United States resisted even diplomatic intervention.

The bodies of the slain Belgian soldiers were returned to Brussels on April 14. One of the pivotal conversations in the course of the genocide took place around that time, when Willie Claes, the Belgian foreign minister, called the State Department to request "cover" "We are pulling out, but we don't want to be seen to be doing it alone," Claes said, asking the Americans to support a full UN withdrawal. Dallaire had not anticipated that Belgium would extract its soldiers, removing the backbone of his mission and stranding Rwandans in their hour of greatest need. "I expected the ex-colonial white countries would stick it out even if they took casualties," he remembers. "I thought their pride would have led them to stay to try to sort the place out. The Belgian decision caught me totally off guard. I was truly stunned."

Belgium did not want to leave ignominiously, by itself. Warren Christopher agreed to back Belgian requests for a full UN exit. Policy over the next month or so can be described simply: no U.S. military intervention, robust demands for a withdrawal of all of Dallaire's forces, and no support for a new UN mission that would challenge the killers. Belgium had the cover it needed.

On April 15 Secretary Christopher sent Ambassador Albright at the UN one of the most forceful documents produced in the entire three months of the genocide. Christopher's cable instructed Albright to demand a full UN withdrawal.The directions, which were heavily influenced by Richard Clarke at the NSC and which bypassed Steinberg, were unequivocal about the next steps. Saying that the United States had "fully" taken into account the "humanitarian reasons put forth for retention of UNAMIR elements in Rwanda," Christopher wrote that there was "insufficient justification" to retain a UN presence:

The international community must give highest priority to full, orderly withdrawal of all UNAMIR personnel as soon as possible....

We will oppose any effort at this time to preserve a UNAMIR presence in Rwanda.... Our opposition to retaining a UNAMIR presence in Rwanda is firm. It is based on our conviction that the Security Council has an obligation to ensure that peacekeeping operations are viable, that they are capable of fulfilling their mandates, and that UN peacekeeping personnel are not placed or retained, knowingly, in an untenable situation."'

"Once we knew the Belgians were leaving, we were left with a rump mission incapable of doing anything to help people," Clarke remembers. "They were doing nothing to stop the killings."

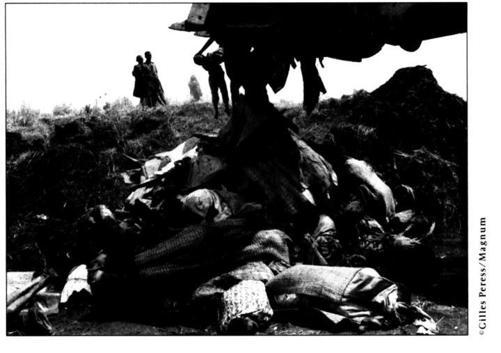

But Clarke underestimated the deterrent effect that Dallaire's very few peacekeepers were having. Although many soldiers hunkered down, terrified, others scoured Kigali, rescuing Tutsi, and later established defensive positions in the city, opening their doors to the fortunate Tutsi who made it through roadblocks to reach them. One Senegalese captain, Mbaye Daigne, saved 100 or so lives single-handedly. Some 25,000 Rwandans eventually assembled at positions manned by UNAMIR personnel. The Hutu were generally reluctant to massacre large groups ofTutsi if foreigners (armed or unarmed) were present. It did not take many UN soldiers to dissuade the Hutu from attacking. At the Hotel des Mille Collines, ten peacekeepers and four UN military observers helped to protect the several hundred civilians sheltered there for the duration of the crisis. About 10,00() Rwandans gathered at the Amohoro Stadium under light UN cover. Beardsley, Dallaire's executive assistant, remembers, "If there was any determined resistance at close quarters, the government guys tended to back off." Kevin Aiston, the Rwanda desk officer at the State Department, was keeping track of Rwandan civilians under UN protection. When Deputy Assistant Secretary Bushnell told him of the U.S. decision to demand a UNAMIR withdrawal, he turned pale. "We can't," he said. Bushnell replied,"The train has already left the station."

On April 19 the Belgian colonel Luc Marchal delivered his final salute to Dallaire and departed with the last of his soldiers. The Belgian withdrawal reduced UNAMIR's troop strength to 2,100. What was more crucial, Dallaire lost his best troops. Command and control among Dallaire's remaining forces became tenuous. Dallaire soon lost every line of commniu- nication to the countryside. He had only a single satellite phone link to the outside world.