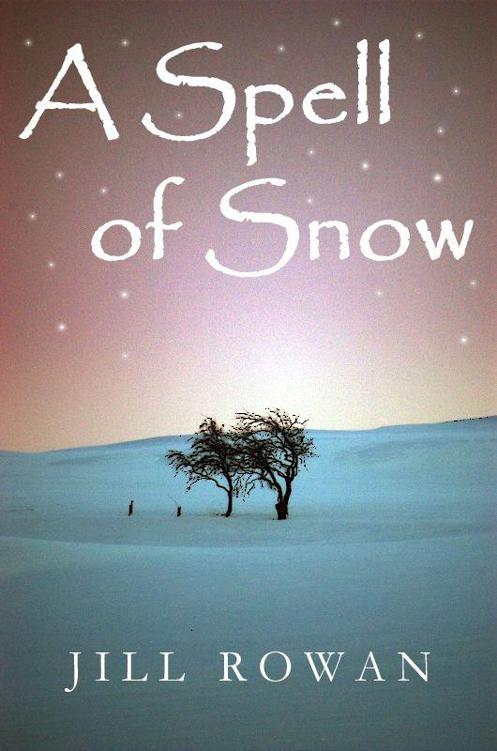

A Spell of Snow

Authors: Jill Rowan

A

Spell of Snow

A

novella

by

JILL

ROWAN

Copyright © 2013 Jill Rowan

All rights reserved

No part of this story may be

used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the

author or Sparkling White Publishing except for brief quotations used for

promotion or in reviews. Names, characters, and incidents in this story are

fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is entirely

coincidental.

Find the author’s blog at

jillrowan.wordpress.com

Or find her on Twitter

@JillRowan1

Other works by Jill Rowan:

The Legacy in paperback:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Legacy-Jill-Rowan/dp/1907777555

The Legacy on Kindle:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Legacy-ebook/dp/B0067PP2BY

The Dream:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Dream-Jill-Rowan/dp/1907777822

A Christmas Gift:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/A-Christmas-Gift-ebook/dp/B00AHH6FGO

I kicked a stone and watched it skitter over a pavement

slick with wetness, and then turned with a shiver to head towards my auntie’s

house through a damp wind and stuttering drizzle.

So this was the

British winter. It certainly didn’t live up to its reputation. Was it

always

like this in January? Where were the several feet of snow, the hot toddies, the

snowmen, and above all, the magic? The air should have been icy, dry, and crisp

like chilled wine; not this clammy, dispiriting cold that seemed to pervade

everything with its gloom.

The cheerless

terraced house in which I now lived loomed ahead, and I opened the front door

with a scowl. The carpet runner was threadbare, the green paint on the skirting

board chipped, and the peeling wallpaper appeared to be two hundred years old.

Everything about England seemed so

grubby

somehow.

I thrust intrusive

thoughts of my old life to the back of my mind as I headed to the kitchen to

grab a snack. Auntie Cheryl wouldn’t be home for another two hours, but I was

used to fending for myself. I checked my mobile phone as I made cheese on

toast: no missed calls, no texts. My friends back in Australia were already

dropping away, one by one.

I sniffed a little

as I took my snack into the living room and turned on the TV. By the time the

closing credits of Home and Away had gone up I was in fully-fledged sobs, and

when my auntie banged in through the front door I had to grab a tissue and wipe

my eyes quickly.

‘Tilly, are you in

there?’ she called out.

‘Where else would

I be?’ I shouted back, irritated.

‘Well, can you

come into the kitchen?’ she said, her tone impatient. ‘I want to talk to you.’

I got up

reluctantly from the sofa. Any kind of talk with Auntie Cheryl was likely to be

bad news.

She was clattering

saucepans, her face pink and her blonde hair wet from the rain. ‘It wouldn’t

hurt you to cook something, you know,’ she said. ‘You used to cook for your

mum, didn’t you?’

I shrugged. ‘That

was different. Anyway, I’ve had some cheese on toast.’ I couldn’t help adding,

‘I didn’t realize you just wanted me to come and live here to be your skivvy.

What d’you expect, dinner on the table when you get home?’

She reddened. ‘It

would be nice, just once in a while. It’s not as if you’ve been doing your

homework, is it?’

I lounged

awkwardly against the kitchen worktops. I didn’t want to talk about boring

homework.

She threw beans

into a saucepan with some force. ‘I had a letter from the school this morning.

Apparently you show no interest in class and you haven’t handed in a single

piece of homework since you started there.’

I raised my hands

in a gesture of hopelessness. ‘What’s the point? I’m not interested in all that

rubbish, and besides, I don’t know where I am with these GCSEs – they’re not

what I’m used to.’

‘I know it’s

hard,’ she said, stirring the beans, ‘but you’ll adjust if you work at it.

Maybe it’s partly because you missed a lot of schooling back in Australia.’

‘I don’t

want

to adjust to it,’ I said with feeling. ‘I just want to go home. I hate the

school and I hate it here. Why’d you even agree to take me? They’d have let me

stay at the homestead if you hadn’t put your oar in. I’d have been looking

forward to a barbecue

in the sunshine

right now, and I wouldn’t have

lost the horses, and...’ I choked back a fresh sob.

She flushed even

more brightly. ‘Look, Tilly, it’s hard enough without you constantly harking

back to what you’ve lost. I’m trying my best, but you’re just determined to

stay miserable, as far as I can tell.’

‘I’m

not

determined to stay miserable,’ I protested. ‘It’s only six months since Mum

died. Do you really think I should have got over it that quickly?’

She pushed back

her hair and wiped her forehead with the back of her hand. ‘No, of course not,

but I can’t fix that. I can’t make it all go away – I can’t make it all right

again.’

‘I don’t want you

to!’ I found myself shouting. ‘I hardly know you, and I never wanted to come to

this horrible country in the first place! It’s all

your

fault.’

Her face sort of

crumpled, and it was obvious I’d hurt her, but I couldn’t stand to be in that

house a minute longer; I had to get away. I ran out of the room, ignoring her

shouts to me to come back, grabbed my coat, and slammed out of the front door.

My throat was

tight with emotion as I ran down the road. My coat flapped around me and the

drizzle misted my face and hair, adding to the wetness of tears on my cheeks. I

ran until I had no breath left, and then, just as I slowed, panting, to a

reluctant halt, a bus pulled up on the opposite side of the road. I didn’t care

where it was going, I just needed to escape. I didn’t even look at the

destination as I scrubbed quickly at my face to wipe away the tear stains, and

hopped on.

‘As far as you’re

going,’ I told the driver, still breathless.

He gave me an odd

look and looked me over for a second, but then shrugged. ‘That’ll be

two-fifty.’

I handed over the

money and took my ticket quickly as it ejected from the machine. The driver was

still regarding me with slight concern, so I adopted an air of confidence as I

took my seat, holding my head high.

The bus was only

half full, and as it lumbered through the suburban streets I realized with a

touch of alarm that it wasn’t heading into town, but out of it. People drifted

off at every stop, and I passed the time trying to imagine the types of home

they were heading for. The stooped old man wrapped in a thick scarf was going to

visit his daughter, I decided, and I saw the scene in my mind as she opened the

door and gave him a welcoming hug. The young woman with a toddler in a

pushchair was returning to her small house – her husband was already home,

cooking dinner for the three of them. The happy couple who seemed interested

only in each other were on their way to meet her parents. A bitter weight

formed in my stomach as I imagined all these happy family scenes. I scrunched

my eyes tight to keep any more tears from forming. What use were all the tears

anyway? Nothing was going to bring my mum back; Auntie Cheryl was right about

that.

Eventually there

were only two women on the bus besides me, and I peered through the window in

surprise as snow began to fall outside. By the time the bus pulled up in the

middle of nowhere it was falling in great clumps and the ground was white.

The women both

stood up to get off, and I gazed out at the expanse of fields with a sprinkling

of houses with a slight sense of unease. The driver looked back at me and said,

‘This is it, love. Rillsend. You sure you really want to get off here? I’m

heading back into town now and the next bus isn’t for two hours. Don’t miss it;

it’s the last one.’

There was no way I

could back down now and head home with my tail between my legs. No, I’d just

hang around here for a while, long enough to give Auntie Cheryl a bit of a

scare but not long enough for her to do anything too drastic. ‘I’m fine,

thanks,’ I replied as nonchalantly as I could manage, and skipped down the step

before he had a chance to say anything more.

I started walking

briskly in the same direction as the two women, and after a moment the bus

growled off down the lane behind me. Before long, the women were swallowed into

the darkness and driving snow. I shivered when I realized I was alone, and

pulled my coat tighter as the snow fell more thickly and the wind bit through

my thin school uniform blouse. There were no street lights out here either,

which was slightly scary. I took a quick look at my mobile phone; it was six

o’clock. No messages of concern from Cheryl, though, which proved my point –

she didn’t care about me; she’d taken me in out of duty. Then I noticed the ‘no

signal’ indicator. I wasn’t more than five miles out of town, surely? Maybe Rillsend

was in some sort of black spot. Well, it was a tiny place. I couldn’t

understand why the bus stopped there at all.

I kept on walking

doggedly, ignoring the continuing snowfall as I dwelled on my unhappiness. I

thought about my old life with my mum, and the homestead, and the horses. More

tears rolled down my cheeks as I recalled how hard my mum had worked to build

up the riding centre, and how I’d loved to help, so much so that I’d bunked off

school far too often. But Mum had understood – there were better things to do

in life than study.

It was the cold

that roused me. The wind was stronger, the snow had become a blizzard, and I

was struggling through a couple of inches of snow in a pair of inadequate

trainers. I pivoted around, looking for any sign of the two women I’d been

following, or at least the couple of houses I’d seen from the bus, but by now I

was in a country lane surrounded by fields on all sides.

I took out my

mobile again, and noted with a shudder that there was still no signal. Still,

all I had to do was retrace my steps and I’d be back at the bus stop soon

enough. Then I’d just wait and catch the last bus back – no harm done except to

the non-existent relationship I had with my aunt.

I started back

down the lane, but the snow was falling more thickly than ever, and if it

hadn’t been for the hedges I wouldn’t even have been able to follow the

direction of the road. After what seemed like an hour I was sure I must have

walked far enough to get back to the bus stop and far beyond, but there were

still fields in every direction. Where had the houses gone?

In panic I began to run, my trainers

slipping in the fresh snow, my feet numb with cold. There

had

to be a

house somewhere nearby. I pulled out my mobile again and stared uselessly at

the ‘no signal’ symbol. I supposed I ought to send a text to Auntie Cheryl

anyway, just in case I passed through a pocket of signal at some point. I

swallowed my pride and keyed,

I’m sorry. I’m stuck in the middle of nowhere

at Rillsend. Could you come and get me?

I pressed send and hoped she’d

actually be able to find me if she did drive out here. With the snow this

thick, driving would be difficult. Then it struck me – not one car had passed

me. The last vehicle I’d seen was the bus. Surely that couldn’t be right, even

in the middle of nowhere?

I started running

again, but I was getting tired, and I stumbled, falling into the snow with a

shriek and grazing my knees on sharp stones protruding from the dirt track

beneath. I sat and looked at the dark blood mixing with snow and just gave

myself up totally to sobs. I’d wanted to get away from my aunt, from everything

I hated about my new life, but now that my anger had dissipated I just felt

like a fool.