A Summer to Die (3 page)

Authors: Lois Lowry

That same truck was parked at the end of the road, beside a tiny, weatherbeaten house that looked like a distant, poorer cousin of the one I'd passed. An elderly cousin, frail but very proud. There was smoke coming out of the chimney, and curtains in the two little windows on either side of the door. A dog in the yard, who thumped his tail against a snowbank when he saw me coming. And beside the truckâno, actually in the truck, or at least with his head inside it, under the hood, was a man.

"Hi," I called. It would have been silly to turn around and start walking home without saying anything, even though I've promised my parents all my life that I would never talk to strange men.

He lifted out his head, a gray head, with a bright red woolen cap on it, smiledâa nice smileâand

said, "Miss Chalmers. I'm glad you've come to visit."

"Meg," I said automatically. I was puzzled. How did he know who I was? Our name isn't even on the mailbox.

"For Margaret?" he asked, coming over and shaking my hand, or at least my mitten, leaving a smear of grease on it. "Forgive me. My hands are very dirty. My battery dies in this cold weather."

"How did you know?"

"How did I know Meg for Margaret? Because Margaret was my wife's name; therefore, one of my favorite names, of course. And I called her Meg at times, though no one else did."

"They call me Nutmeg at school. I bet no one ever called your wife Nutmeg."

He laughed. He had beautiful blue eyes, and his face moved into a new pattern of wrinkles when he laughed. "No," he admitted, "they didn't. But she wouldn't have minded. Nutmeg was one of her favorite spices. She wouldn't have made an apple pie without it."

"What I meant, though, when I said, 'How did you know?' was how did you know my name was Chalmers?"

He wiped his hands on a greasy rag that was hanging from the door handle of the truck. "My

dear, I apologize. I have not even introduced myself. My name is Will Banks. And it's much too cold to stand out here. Your toes must be numb, even in those boots. Come inside, and I'll made us each a cup of tea. And I'll tell you how I know your name."

I briefly envisioned myself telling my mother, "So then I went in his house," and I briefly envisioned my mother saying, "You went in his

house?

"

He saw me hesitate, and smiled. "Meg," he said, "I'm seventy years old. Thoroughly harmless, even to a beautiful young girl like you. Come on in and keep me company for a bit, and get warm."

I laughed, because he knew what I was thinking, and very few people ever know what I'm thinking. Then I went in his house.

What a surprise. It was a tiny house, and very old, and looked on the outside as if it might fall down any minute. For that matter, his truck was also very old, and looked as if

it

might fall down any minute. And Mr. Banks himself was old, although he didn't appear to be falling apart.

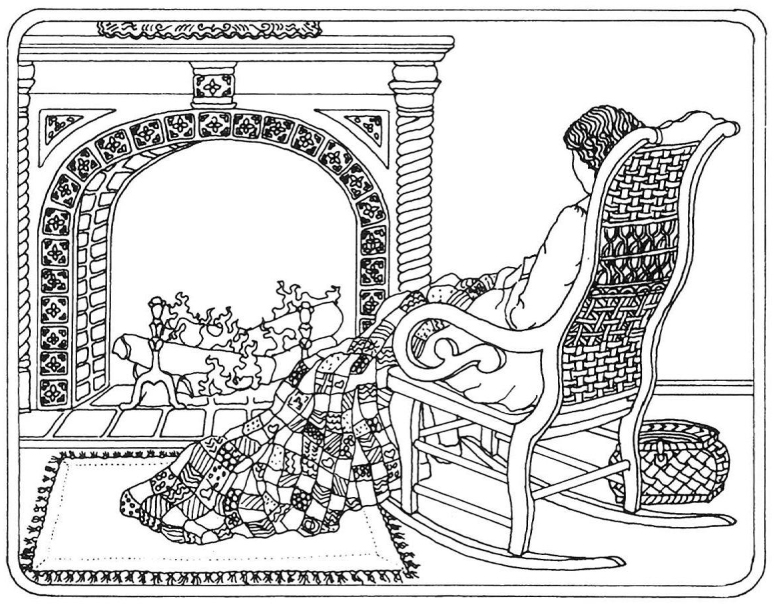

But inside, the house was beautiful. Everything was perfect, as if it were a house I'd imagined, or dreamed up with a set of paints. There were only two rooms on the first floor. On one side of the little front hall was the living room: the walls were painted white, and there was an oriental rug on the 24

floor, all shades of blues and reds. A big fireplace, with a painting that was a real painting, not a print, hanging over the mantel. A pewter pitcher standing on a polished table. A large chest of drawers with bright brass handles. A wing chair that was all done in needlepoint â all done by hand, I could tell, because my mother does needlepoint sometimes. Sunlight was pouring in the little windows, through the white curtains, making patterns on the rug and chairs.

On the other side of the hall was the kitchen. That's where Mr. Banks and I went, after he had shown me the living room. A wood stove was burning in the kitchen, and a copper kettle sat on top of it, steaming. A round pine table was laid with woven blue mats, and in the center of it a blue and white bowl held three apples like a still life. Everything was scrubbed and shiny and in the right place.

It made me think of a song that we sang in kindergarten, when we sat at our desks and folded our hands. "We're all in our places with bright shiny faces," we used to sing. I could hear the words in my mind, the little voices of all those five-year-olds, and it was a good memory; Mr. Banks' house was like that, a house warm with memories, of things in their places, and smiling.

He took my jacket and hung it up with his, and

poured tea into two thick pottery mugs. We sat at the table, in pine chairs that gleamed almost yellow from a combination of old wood, polish, and sunlight.

"Is yours the little room at the top of the stairs?" he asked me.

How did he know about the little room? "No," I explained. "I wanted it to be. It's so perfect. You can see the other house across the field, you know" âhe nodded; he knew "âbut my father needed that room. He's writing a book. So my sister and I have the big room together."

"The little room was mine," he said, "when I was a small boy. Sometime when your father isn't working there, go in and look in the closet. On the closet floor you'll find my name carved, if no one's refinished the floor. My mother spanked me for doing it. I was eight years old at the time, and I'd been shut in my room for being rude to my older sister."

"You lived in my house?" I asked in surprise.

He laughed again. "My dear Meg," he said, "

you

live in

my

house.

"My grandfather built that house. Actually, he built the one across the field, first. Then he built the other one, where you live. In those days families stuck together, of course, and he built the second house for his sister, who never married. Later he 26

gave it to his oldest sonâmy fatherâand my sister and I were both born there.

"It became my house when I married Margaret. I took her there to live when she was a bride, eighteen years old. My sister had married and moved to Boston. She's dead now. My parents, of course, are gone. And Margaret and I never had children. So there's no one left but me. Well, that's not entirely trueâthere's my sister's son, but that's another story.

"Anyway, there's no one left here on the land but me. There were times, when I was young, when Margaret was with me, when I was tempted to leave, to take a job in a city, to make a lot of money, butâ" He lit his pipe, was quiet for a minute, looking into the past.

"Well, it was my grandfather's land, and my father's, before it was mine. Not many people understand that today, what that means. But I

know

this land. I know every rock, every tree. I couldn't leave them behind.

"This house used to be the hired man's cottage. I've fixed it up some, and it's a good little house. But the other two houses are still mine. When the taxes went up, I just couldn't afford to keep them going. I moved here after Margaret died, and I've rented the family houses whenever I come across someone who has reason to want to live in this wilderness.

"When I heard your parents were looking for a place, I offered the little house to them. It's a perfect place for a writerâthe solitude stimulates imagination, I think.

"Other people come now and then, thinking it might be a cheap place to live, but I won't rent to just anyone. That's why the big house is empty nowâthe right family hasn't come along."

"Do you get lonely here?"

He finished his tea and set the cup down on the table. "No. I've been here all my life. I miss my Margaret, of course. But I have Tip"âthe dog looked up at his name, and thumped his tail against the floorâ"and I do some carpentry in the village now and then, when people need me. I have books. That's all I need, really.

"Of course," he smiled, "it's nice to have a new friend, like you."

"Mr. Banks?"

"Oh please, please. Call me Will, the way all my friends do."

"Will, then. Would you mind if I took your picture?"

"My dear," he said, straightening his shoulders and buttoning the top button of his plaid shirt. "I would be honored."

The light was coming in through the kitchen window onto his face: soft light now; it had become

late afternoon, when all the harsh shadows are gone. He sat right there, smoked his pipe, and talked, and I finished the whole roll of film, just shooting quickly as he gestured and smiled. All those times when I feel awkward and ineptâall those times are made up for when I have my camera, when I can look through the viewfinder and feel that I can control the focus and the light and the composition, when I can capture what I see, in a way that no one else is seeing it. I felt that way while I was taking Will's picture.

I unloaded the exposed film and carried it home in my pocket like a secret. When I looked back from the road, Will was by his truck again, waving to me; Tip was back by his snowbank, thumping his tail.

And deep, way deep inside me somewhere was something else that kept me warm on the walk home, even though the sun was going down and the wind was coming over the piles of snow on either side of the road, blowing stinging powder into my eyes. It was the fact that Will Banks had called me beautiful.

February is the worst month, in New England. I think so, anyway. My mother doesn't agree with me. Mom says April is, because everything turns to mud in April; the snow melts, and things that were buried all winterâdog messes, lost mittens, beer bottles tossed from carsâall reappear, still partly frozen into icy mixtures that are half the gray remains of old snow and half the brown beginnings of mud. Lots of the mud, of course, ends up on the kitchen floor, which is why my mother hates April.

My father, even though he always recites a poem that begins "April is the crudest month" to my mother when she's scrubbing the kitchen floor in the spring, agrees with me that it's February that's worst. Snow, which was fun in December, is just boring, dirty, and downright cold in February. And the same sky that was blue in January is just nothing but white a month laterâso white that sometimes you can't tell where the sky ends and the land begins. And it's cold, bitter cold, the kind of cold where you just can't go outside. I haven't been to see Will, because it's too cold to walk a mile up the road. I haven't taken any pictures, because it's too cold to take off my mittens and operate the camera.

And Dad can't write. He goes in the little room and sits, every day, but the typewriter is quiet. It's almost noisy, the quietness, we are all so aware of it. He told me that he sits and looks out the window at all the whiteness and can't get a grip on anything. I understand that; if I were able to go out with my camera in the cold, the film wouldn't be able to grip the edges and corners of things because everything has blended so into the colorless, stark mass of February. For Dad, everything has blended into a mass without any edges in his mind, and he can't write.

I showed him the closet floor, where

William

is carved into the pine.

"Will Banks is a fascinating man," Dad said, leaning back in his scruffy leather chair in front of the typewriter. He was having a cup of coffee, and I had tea. It was the first time I had visited him in the little room, and he seemed glad to have company. "You know, he's well educated, and he's a master cabinetmaker. He could have earned a fortune in Boston, or New York, but he wouldn't leave this land. People around here think he's a little crazy. But I don't know, I don't know."

"He's not crazy, Dad. He's nice. But it's too bad he has to live in that teeny house, when he owns both these bigger ones that were his family's."

"Well, he's happy there, Meg, and you can't argue with happiness. Problem is, there's a nephew in Boston who's going to make trouble for Will, I'm afraid."

"What do you mean? How can anyone make trouble for an old man who isn't bothering anybody?"

"I'm not sure. I wish I knew more about law. Seems the nephew is the only relative he has. Will owns all this land, and the housesâthey were left to himâbut when he dies, they'll go to this nephew, his sister's son. It's valuable property. They may not look like much to you, Meg, but these houses are real antiques, the kind of things that a lot of people from big cities would like to buy. The nephew, apparently, would like to have Will declared what the law calls 'incompetent'âwhich just means crazy. If he could do that, he'd have control over the property. He'd like to sell it to some people who want to build cottages for tourists, and to turn the big house into an inn."

I stood up and looked out the window, across the field, to where the empty house was standing gray against the whiteness, with its brick chimney tall and straight against the sharp line of the roof. I imagined cute little blue shutters on the windows, and a sign over the door that said "All Major Credit Cards Accepted." I envisioned a parking lot, filled with cars and campers from different states.

"They can't do that, Dad," I said. Then it turned into a question. "Can they?"

My father shrugged. "I didn't think so. But last week the nephew called me, and asked if it were true, what he had heard, that the people in the village call Will 'Loony Willie.'"

"

'Loony Willie'?

What did you say to him?"