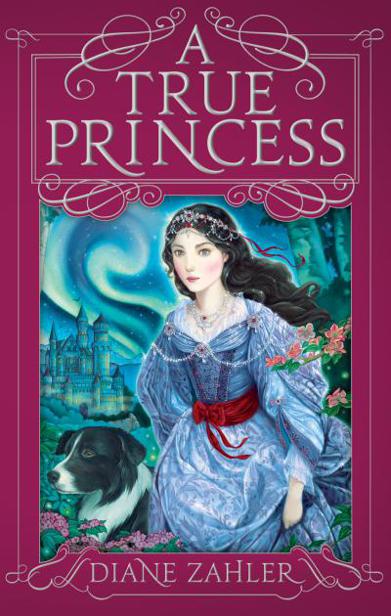

A True Princess

DIANE ZAHLER

A

TRUE

PRINCESS

For Ben, the real Prince Tycho

My deepest gratitude to:

Barbara Lalicki and Maria Gomez, for their diligence, patience, and skill

Shani Soloff, for her tireless readings and inspired suggestions

Debra and Arnie Cardillo, for their encouragement and support

Kathy Zahler, for listening, reading, and cheering

And Phil Sicker, who is not least but most—most constant reader, most exceptional editor, most devoted husband

Contents

I

shall run away!” I whispered furiously to Ove the sheepdog as we crouched beneath the farmhouse window listening to the conversation inside. I could hardly believe what I was hearing.

“I meant what I said,” I heard Ylva say to her husband, Jorgen. “Lilia will have to go. I have spoken to Odur the miller. He and his wife have need of a serving girl, and they would be pleased to take her.”

Lilia

. The sound of my name on her lips horrified me. I covered my mouth so I wouldn’t make any noise, though I wanted to scream. The miller was a burly man with a rough manner and rougher hands. He had six children and he beat them all, and I knew he would strike a servant even more frequently.

“We have no room for one more,” Ylva continued. “Would you prefer to give Odur one of your own children?” I raised my head just enough to peer through the window and saw Jorgen smoking his last pipe of the day before the fire. Ylva, newly pregnant, sat beside him in the rocking chair.

Jorgen cleared his throat and replied mildly, “I know that my children are not yours, my dear, and that our own baby will have first place in your heart. But I love them. I cannot send Kai or Karina away.”

“Of course you cannot, husband,” Ylva said in an oily tone. “But Lilia is almost thirteen, and old enough to make her own way in the world.”

“I do not think Lilia would want to be the miller’s servant,” Jorgen pointed out.

“I am not asking you,” Ylva retorted. “She has taken advantage of us long enough. These ten years and more we have fed her and clothed her, and she has been as useless to us as a barren ewe. It is time for her to go.”

“Now, wife—,” Jorgen said calmly.

She turned on him ferociously, and I stooped lower so that she would not see me through the window. “Do you want this babe I am carrying to go without? How shall we feed him, with Lilia eating us out of house and home?”

“She does not eat so much,” Jorgen protested. “And she could help care for the baby.”

“Karina will do that,” Ylva said to him. “She can take over Lilia’s indoor duties as well, and Kai can surely mind the sheep alone. We have no need for Lilia. And besides, the miller has offered to pay us in coppers and to give us as much flour as we might need for next winter.”

Jorgen sighed deeply. He knew, as I did, that when Ylva’s mind was set on something, there was no changing it. She had once made Jorgen walk miles from Hagi, the village nearest where we lived, to Brenna Town because she longed for strawberries and there were none at our market. What she wanted she got. I would have to go; that was clear. But I swore to myself that I would not go to the miller. I would not be sold like a slave for a few pounds of flour!

I sat beneath the window, stroking Ove and trembling with rage and dread as I heard Jorgen and Ylva climb the ladder to the sleeping loft, where Kai and Karina already slept. I knew now that the old saying “Eavesdroppers seldom hear anything good about themselves” was true.

I repeated the conversation over and over in my mind. Ylva was right when she said that I was a useless servant. I did daydream often, and I forgot to do half the things she demanded, or I did them poorly. I was never comfortable enough on a bed, nor a cot or pallet, to sleep well at night, so I often dozed off over the washing-up or fell into a dream in the middle of sweeping. I cooked porridge so full of lumps that it was nearly inedible. Ylva kept me only because Jorgen insisted.

I was about two years old when Jorgen, out fishing in the river, grabbed a strange, rough basket as it floated past. He found me inside, sound asleep. The river came down from the mountain glaciers and was ice-cold. If the basket had tipped in the swift current or leaked, I would have perished from the freezing water. But I was perfectly dry, and when I opened my eyes—the color of spring violets in this land of the blue-eyed—Jorgen was overcome with astonishment and could not leave me to the river. He carried me home to his new wife and two motherless children—his son, Kai, who was close to my age, or so they guessed, and his daughter, Karina, who was five years older. I had stayed with them ever since, but I certainly was not part of the family, and Ylva never let me forget that. I helped Kai with the shepherding, and Karina and Ylva with the household chores; and I slept on a pallet in the barn with the sheep. Ylva did not even let me eat at the table with the others.

Finally I stood and walked out across the fields, as I liked to do at night when I could not sleep. It was a late spring evening, not long before Midsummer, the longest day of the year. For a week or two before and as long after, the sun did not set at all but hovered at the edge of the horizon, casting a weak glow over the night. My eyes were used to the dim light, and I could see in it almost as clearly as in daylight.

I tried to decide what I should do. I could not stay, I knew that. But where could I go? I had no family, no friends besides Kai and Karina. After hours of walking, I came up with a plan. As a baby I had come down the river from the north, and so I resolved that I would leave the next night and head back that way. Maybe there was someone upriver who knew me, an uncle or a cousin who might welcome me into his or her home. But why, I wondered, had no one ever come looking for me? This question had plagued me all my life. Who had placed me in the basket, and why? Had someone saved me from danger? Or had someone tried to kill me by putting me into the icy water?

I shook my head to clear it. Perhaps I would find the answers if I walked north. Perhaps I would even find a real family of my own.

At last my legs grew tired, and I headed back to the barn. I passed our nisse, the little elf that lived under the house and protected the farm. Every farm I knew of had a nisse, all of them slight creatures in red caps, only a bit more than waist high, with long gray beards and pointed elvish ears. Some were more mischievous than others. When our nisse was annoyed—which was frequently—he would turn things upside down, from mugs to milk pails to beds; but he did not do any real damage. He did not like being seen, and we never spoke. In fact, if I stared at him or appeared to notice him in any way, he would get furious. His face would grow as red as his cap, and I would run back to the house as fast as I could, before he could turn

me

upside down. Sometimes I snuck a morsel of food and left it for him. I never saw him take it, but it was always gone soon after I left it. I was a little surprised to see him, as all the nisses disappeared for a time around Midsummer. No one knew exactly why, but I liked to imagine them having their own Midsummer’s Eve celebration, scowling and grumbling and playing tricks on one another around a big Midsummer bonfire.

I dozed for a while in the barn among the warm, woolly sheep, and when the sky lightened I rose and went into the farmhouse. Before long I heard stirrings overhead in the loft, and the family descended, first Kai and Karina, then Jorgen, and finally, yawning and stretching, Ylva.

I met no one’s eyes as I served them their breakfast of tea and porridge. I had decided not to tell anybody that I was leaving, yet I knew that if I looked at Kai or Karina, they would realize at once that something was dreadfully amiss. Ylva and Jorgen ate silently, but Kai ran his spoon through his porridge and said, “The lumps are only as big as pebbles today, Lilia! Have you lost your touch?”

Karina laughed, but I scowled at him. He gave me a quizzical look, and I looked away, hoping he could not read my thoughts.

After breakfast Kai stood and called Ove to him. “Time to take the sheep to pasture,” he told the dog. “Are you ready, Lilia?”

I took off my apron and followed them outside. As we did every day, we opened the barnyard gate, and Ove herded the sheep up the hillside. As soon as they were grazing in the green fields, I headed to a clearing by a brook. Usually Kai and I stayed near the sheep, wandering the fields and talking, but today I longed to be alone. Kai did not take the hint, though, and followed me.

“I can tell you are upset,” he said, settling himself beside me in the soft grass. “What is it? Did Ylva say something terrible?”

“When does your stepmother not say something terrible?” I retorted.

Kai laughed. “I meant something more terrible than usual.”

I longed to tell him. Usually I told him everything. But I did not.

I lay back in the grass, hearing the calls of the sheep in the distance and Ove’s occasional sharp bark as a lamb strayed from the flock. Far above I could see a bird circling—a hawk or a falcon, perhaps. In the North Kingdoms, I had heard, the huge falcons were a threat. A large one could carry off a newborn lamb, and many shepherds dreaded seeing them out hunting. But they never bothered our flocks here in the South, and I loved to watch them soar on the air currents that flowed far above the farm.

“Well?” Kai asked again, pulling my braid to get my attention. “Did she say something to upset you?”

I shook my head and closed my eyes, pretending to sleep. I could not think how to tell him what I had heard and what I planned. Before long I heard him sigh and rise and head back to the flock, and without meaning to, I fell truly asleep.

I soar like a bird, weightless. Below me I can see a river rushing through stands of pine trees, and beyond that, snow-capped mountains rise from a green plain. I look up, and the sky is changed. It is green, and blue, and the purple of wild lavender. The colors pulse with the rhythm of a heartbeat. I have never seen anything so strange, but I am not afraid.

“Lilia, wake up!”

Kai was shaking me, and I roused myself. It was time to bring back the sheep, and I knew I had much to do to prepare for leaving the farm that night. Our walk back was silent, but Kai cast sidelong glances at me, and I had to work hard to ignore the unspoken questions in his blue eyes. I could hardly bear to think of how much I would miss him, and when our hands brushed as we walked, I grabbed his and squeezed it. He grinned at me then, reassured, and I smiled at him.

Back at the farmhouse, we were surprised to see Ylva bustling around the kitchen, looking uncustomarily pleased and contented as she stirred the supper pot. Good smells rose up from the stove. Usually Ylva insisted that plain food was all that a body required, but perhaps in celebration of her decision to get rid of me, she had decided to add some herbs and spices to tonight’s mutton stew.

Well, good riddance to you, too!

I thought resentfully. I would be glad never to see her again.

The family sat at the rough-hewn oak table, and I perched on a stool by the fire with my meal. Ylva ate two large bowlfuls, and Kai and Jorgen did as well. Even I was tempted to ask for a second helping, but I remembered Ylva’s lies about eating them out of house and home and kept quiet.

“A fine supper, wife,” Jorgen said approvingly when he was finished, reaching for his pipe.

“Why, thank you, husband,” Ylva said in a flirtatious tone that made me wince. “Now in return, I need you to do something for me.”

“At your service, madam,” Jorgen said grandly. I exchanged a look with Karina, and rolled my eyes at her. She had to cover her mouth with a napkin to keep a laugh from escaping.

“I need the cradle from the shed,” Ylva said. “I want to clean it and set it up right there, beside the fire.”

“So soon?” Jorgen asked, pushing back from the table. “The baby is not due for months yet.” With that, Ylva’s good mood was gone.

“

Now

, husband!” she commanded.

Jorgen and Kai and I hurried out the door to the shed that housed tools and the items that would not fit in the small house. “I know it is in here somewhere,” Jorgen muttered, holding a candle high to light the gloomy space and pushing aside hoes and rakes and scraps of wood.

I had not been inside the shed since I was a child, when Kai and I would use it in our games of hide-and-seek. Everything that was too broken to use but too valuable to throw away had been thrust inside. It was dark and musty, and the dust we disturbed made me cough. In the candlelight I could make out a broken chair, a child-sized bed frame, and a three-legged stool with only two legs remaining that leaned against the wall. Kai pushed the stool aside. “Father, what is that?” he asked, pointing.

I stared at the object, trying to figure out what it could be. It was shaped like a large bowl or a basket, but it seemed to be made of sticks, woven awkwardly together. The spaces between the sticks were daubed with clay, and strange materials—feathers, bits of wool—were stuck into the clay.

“My goodness,” said Jorgen softly. “I think it is your basket, Lilia—the one I found you in.”

“This is my basket?” I asked, astonished.

“I must have kept it. I hadn’t remembered.”

“The clay is as hard as stone,” Kai observed, tapping it. “It still seems solid and watertight, even after all these years.” He ran his hand over the basket’s rough surface.

“Well,” I said at last, looking at its outlandish construction, “I suppose this proves I am the daughter of the worst basket maker in the land!”

Kai and Jorgen both snorted with laughter, and Jorgen laid a hand on my arm. I imagined from his gentle touch that he was trying to apologize to me for what he knew must happen, and I put my hand over his as if to say

Yes, I know; I forgive you.

With a little more searching, we found the cradle, a carved wooden piece that rested on a curved base so that it would rock side to side. We carried it out of the shed, and in the brighter light of the midsummer evening we could see that it was dusty and full of mouse droppings. I was set to work scrubbing it. Soon the cradle was clean and fresh smelling, and we moved it into the farmhouse, near the fireside as Ylva directed us.