A Wedding in Haiti (14 page)

Read A Wedding in Haiti Online

Authors: Julia Alvarez

We talk for a while, Piti explaining his plans. Tomorrow, they will head up to the mountains with Eli. At his foreman job, Piti has been promised a house for his new family by the owner he calls “

el hombre.

” But so far,

el hombre

hasn’t kept his promise. The problem is complicated because Piti owes

el hombre

money. I can see the worry on the young man’s face. He does not want his wife and little baby living in a two-room shack with the half a dozen other Haitians who are working on the farm.

“You must take the baby in for her vaccines,” I remind Piti. There is a free clinic in the nearby village. Then, since I am the godmother of their wedding, I decide to broach the topic of family planning. Unless it’s too late. Maybe Eseline’s nausea was actually morning sickness.

Piti looks relieved that I’ve brought up the topic. No, it is not possible that Eseline is pregnant. The couple have not had relations since the baby was born. In fact, he has a question for me. Can he have relations with his wife while she is nursing?

I had worried that the question would be more complicated. That I would have to plead ignorance because I’ve never had a child myself. But this one is easy. “Of course, you can have relations, but remember, Eseline

can

get pregnant.”

“And Ludy, will she be okay?”

Now I’m the one confused. “Why shouldn’t she be?”

Piti explains that he has been told that if a man has relations with his wife while she is still nursing, the baby will never learn to walk.

Later, when I tell my stepdaughter this story, she will laugh and say, “I can bet who invented that story!” New mothers too tired and sleep-deprived to deal with horny husbands for whom a headache is no excuse. But a crippled baby might just stop them in their tracks.

“

Ay,

Piti,” I say. “Somebody has been telling you stories.”

But it’s not Eseline he heard it from. Piti grew up mostly in the barracks, living with peers. All his education, including his sex education, came from them. I’m reminded of that boy I first saw, horsing around with other young Haitians after a day in the fields. And how far that boy has come, distinguishing himself as one of the hardest workers, promoted above Dominicans to be the foreman of

el hombre

’s farm. He has taught himself to read, write, play the guitar, compose songs. He has just married the mother of his baby girl and brought them over to live by his side. God’s blessings are raining down on his life.

Mèsi, Jezi, mèsi,

all right.

Upstairs, my mother has still not come out of her bedroom. I go in to check on her. These days, whenever I enter a room and either parent gazes up, I brace myself. Will this be one of those times when they don’t know who I am?

Tonight, my mother’s face lights up when she sees me. “When did you get here?”

I play along—why confuse her. “Bill and I just flew in. We’ll be staying with you for a week. But I hear you’re not feeling well. I’m sorry.”

“I’m feeling fine,” she tells me, having forgotten her earlier story. “I’m so glad you found me here,” she adds, patting a place beside her on the bed for me to sit down. “Tomorrow I’m going home.”

“Yes, I know.” I’m not humoring her. She is absolutely right: she doesn’t remember this place. So how can it be her home? What’s more, she will never be home again, except when—cursed, blessed disease—she forgets to remember she isn’t there. “We came to help you get there.”

“Thank you,” she says, clearly relieved.

My father is wheeled in from the supper table, calling out, “Pitou? Pitou?” The night nurse rings the bell for Don Ramón to come help, as Papi is too heavy a weight for us to lift by ourselves. We go through the rituals of getting them ready for the night: taking out Papi’s teeth, helping Mami brush hers, putting on their nightclothes, giving them their medications. For a while, we had a night nurse who insisted they pray. But mostly, it was the nurse saying the “Our Father” and “Hail Mary,” my parents chiming in with the few phrases they remember,

Give us our daily bread; pray for us now and at the hour of our death; amen, amen.

I tuck them in, join their hands together, and turn off the light. Goodnight, Pitouses, sleep tight.

Back in our room, Bill and I lie in bed talking. One of the pleasures of marriage is having someone to listen to your stories and to tell you theirs. To help you make sense of experience, weave a narrative out of the disparate threads—precisely what my parents are losing, the ability to do this for themselves and for each other.

So many things to talk about! So many details to piece together from the last three days! And more to come in the weeks ahead. Do we just keep doing this? Each day a new batch. Story as a digestive tract, a way to process what has happened and store it away in memories to recount at supper parties—nothing more? As a child, my older sister used to have a recurring nightmare: she’d be put in a room stuffed with beads she had to string together. Just when she was about to finish, the door would open, and a whole new load of beads would pour in. She’d wake up screaming and tell me the story once again. All I could think was, That’s a nightmare? No monsters or murderers, no wild animals about to tear you apart? What could be so scary about endlessly stringing together beads? Now I understand.

But I’m praying to angels on high to bless us with another option: We string the beads into a ladder and climb out the window before the door opens. Story as agency, story that awakens and propels us to change our lives.

When we have seen a thing, what then is the obligation?

Bill and I talk late into the night. Finally, wearily, I ask him, “What do we do now?”

Although he often claims he is no wordsmith, Bill gives me the best answer I’m going to get. “We do what we can. We try to be generous wherever we find ourselves.”

And tonight it happens—what seldom happens in a human family so scattered and stratified, so divided by opportunity that sometimes it’s difficult to recognize the critter at the top as kin to the one at the bottom. Tonight, oh holy night: a disparate group has gathered like pieces of a story under one roof, all having eaten enough, all safe enough for now, all asleep or ready for sleep, except for Don Ramón downstairs with his little radio turned down low to keep him company until dawn when he, too, will get to go home.

TWO

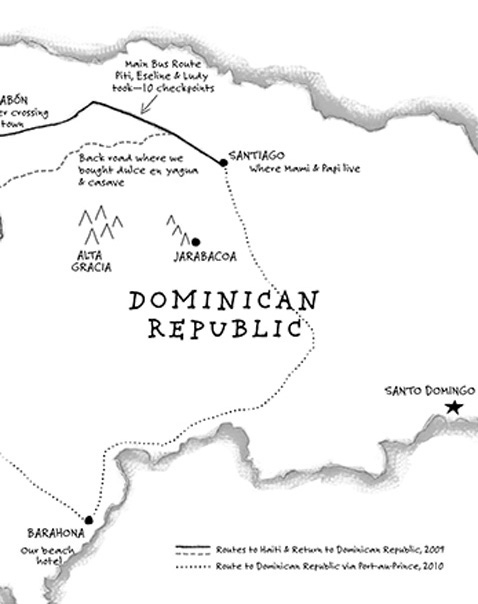

Going Home with Piti after the Earthquake

January 12, 2010, the end of the world

I was talking to my sister in Santiago, the sister who has moved down there to help care for my parents, the sister of the beads nightmare, the sister who is emotive, expansive, and sometimes overreacts. It was my usual end-of-the-work-day phone call to see how the

pitouses

were doing.

“Oh my god!” my sister suddenly cried out.

“What? What?” My heart was in my throat.

In the background, my mother was crying out, a more terrified echo of my own “What? What?”

“It’s nothing, Mami, just a strong wind,” my sister was saying in a pretend calm voice that didn’t fool me. Then, she whispered into the phone, “I think it’s an earthquake. I better go.” And she was off, a click, then silence. I was left with an odd feeling. The feeling of the person who has heard the boy cry wolf before, and this time, hearing the cry, doesn’t know if there is a real wolf at the door.

There was a real wolf at Haiti’s door.

A 7.0 magnitude earthquake, to be exact, on the island of Hispaniola, which sits atop the boundary between two plates in the earth’s crust: one of which, the North American plate, is jamming itself under the other, the Caribbean plate, which has nowhere to go. (Geology as allegory?) Felt as far away as my parents’ house in Santiago, the quake’s epicenter was just fifteen miles southwest of Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, where the clayey soil meant that the houses were like those Biblical ones built on sand. Down they came, the mansions of the rich, and the shacks of the poor, the presidential palace and many other government buildings, hospitals, schools—concrete slabs pancaking down, in a country without building codes, in a city packed with millions of people.

Months later when the final toll was taken—though

final

would be another of those wobbly words, each day or week turning up one more casualty—the Haitian government reported 316,000 dead, 300,000 injured, 1.3 million displaced, 97,300 houses destroyed. Mind-numbing figures, hard to compute unless broken down to one life at a time, one story at a time. “It’s the end of the world! It’s the end of the world!” one terrified young woman screamed in front of a wildly rocking camera.

Which is why, after I turned off the television with the late-breaking news, and realized that my sister had not overreacted, I called Piti. He was back to working for us.

El hombre

had not come through with the promise to build him and Eseline a little casita of their own. Instead, for months, they had been sharing a two-room hut with half a dozen Haitian workers. Piti was feeling increasingly unsettled. Eseline was distracted. Eli mentioned that every time he saw her, she was hanging out, giggling and flirting with her Haitian housemates. All those homesick young fellows, all that free-floating testosterone.

Bill and I offered Piti a job as caretaker, down the mountain, closer to town, on another piece of property Bill had bought, this time not for any humanitarian project, but for us. (Again, the marital us.) With the help of some Haitians, Bill spent ten days building a small house: four rooms, an outdoor kitchen, a back patio, a front porch. The first of January, when his term with

el hombre

was up, Piti moved into that house with Eseline and Ludy.