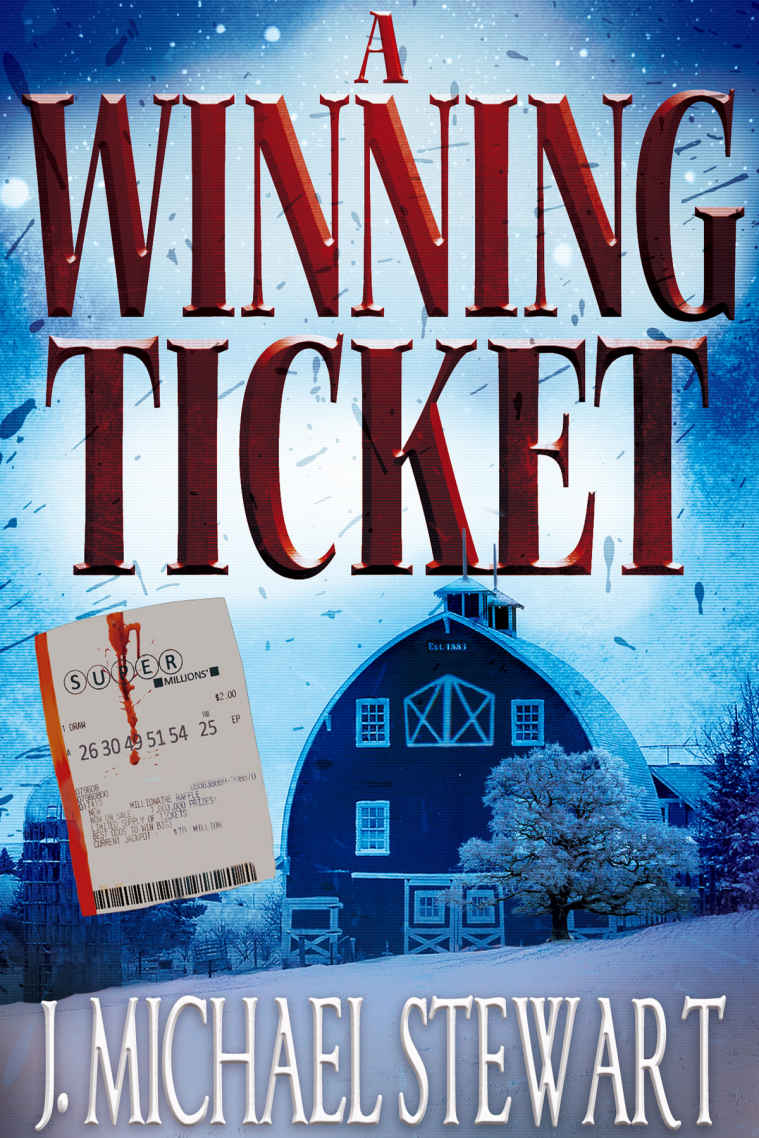

A Winning Ticket

Authors: J. Michael Stewart

J. Michael Stewart

Table of Contents

A Winning Ticket

T

he first snowflakes of the coming storm were beginning to whip against the window glass. Benjamin Zimmerman stood at the kitchen sink and stared outside. The pot of venison stew cooking on the propane stove was almost done. The meat, carrots, and potatoes, along with a pan of fresh-made biscuits, now cooling on the countertop, melted together into a mouthwatering aroma that wafted through the house.

A blizzard warning had been issued earlier in the day, and the local weatherman was predicting twelve to fourteen inches of new snow, with winds gusting to around fifty miles an hour. That kind of wind could produce drifts of several feet. Soon, the visibility would drop to almost zero, and Benjamin would not be able to see past the front porch that lay just beyond the small kitchen window.

This week it was Benjamin’s turn to make supper. Harrison, his brother, was outside feeding and watering the four horses and putting fresh hay out for the cattle. Benjamin knew that Harrison hated doing farm chores, but he disliked kitchen duty even more. Benjamin preferred to be outside in the fresh air, taking care of the animals—taking care of the farmland he loved—but in order to placate Harrison, he had agreed to cook dinner every other week.

Benjamin pressed his forehead against the window of the hundred and twenty-year-old farmhouse he shared with his brother. Neither had ever married or had children, which left the house hauntingly empty at times.

Their great-great-grandfather had purchased the farm in the late eighteen-hundreds, and it had been passed down through the family ever since. The house itself was a small two-story, reminiscent of late nineteenth-century architecture, with white clapboard siding. Inside were three small bedrooms, one tiny bathroom, a living room, and a combination kitchen and dining area. But for what the house lacked in size, it made up for in character. Benjamin loved the old hardwood floors and the hand-hewn stone fireplace in the living room. They rarely used it anymore, opting instead for the modern furnace, but the fireplace brought back fond memories for Benjamin. When he was a child, his grandfather would sit on the stone bench and roast chestnuts over the open flame. When they were done, he would toss the still hot nuts to Benjamin, who would juggle them in his hands, letting them cool, before peeling them and popping them into his mouth.

When Benjamin thought of the eight-hundred acres that surrounded the house, he felt the weight of the responsibility that had fallen on his and Harrison’s shoulders. Roughly one-third of the acreage was planted in corn, another third in soybeans, and the rest was a combination of pasture, wooded areas, and buildings. Of course, all the crops had been harvested several months ago, which left the land brown and seemingly devoid of life—save for the few animals they had left. Harrison often complained at the farm’s lifelessness during the winter months, but Benjamin saw it differently. There was always something to do—always some animal that needed taken care of—so Benjamin loved winter just as much as the other three seasons. Instead of viewing it as depressing and cold, he saw it as a time to catch up on work that sometimes fell by the wayside during the busier summer months.

Benjamin was the oldest of the brothers—by exactly ten minutes. Although they both had the same dark eyes, square jaw, and tall, slender frame, they were fraternal, not identical, twins. When their mother found out she was having twin boys, she had insisted on naming them Benjamin and Harrison because, according to her, a distant relative had once served as President Harrison’s personal secretary. Benjamin thought the story was probably total bullshit, but he never told his mother that. That kind of family disrespect would have earned him a swift thrashing with a hickory switch—his mother’s favorite tool to keep her two rambunctious sons in line.

They used to be rambunctious, Benjamin recalled. Harrison especially loved to push parental boundaries. Smiling to himself, Benjamin remembered the time when they were eight years old and Harrison booby-trapped the mailbox with an M-80 firecracker. They had watched, with great anticipation, the result from the living room window. Damn near blew the mailman’s hand off.

Benjamin had tried harder to gain his mother’s approval—and avoid her switch.

He continued to gaze out the window.

The clouds had lowered over the past several hours, and daylight was quickly fading. The wind had also picked up and was now blowing and lifting the snow into swirls and eddies that moved along the landscape like a flowing river. Benjamin saw no sign of his brother yet, and he began to worry. Perhaps he should have gone with him. The two of them could have completed the chores in half the time and both would have been safely inside the house by now. The winter storm was bearing down on the Zimmerman farm, and within the next half-hour, it would be dangerous, even life-threatening, to be outside.

January snowstorms like this were not uncommon in northern Nebraska—still, they weren’t to be taken lightly. It was not unusual to hear of someone who got stranded outside during a blizzard and died from exposure to the bitter temperatures.

Just last year, one of the Zimmerman’s neighbors, Mrs. Hannaby, an elderly widow who lived alone, had gone out to check her mail during a winter storm. While returning to the house, she had tripped and fallen on the front steps and broken her hip. Searchers found her five days later, buried under a three-foot snow drift.

Benjamin turned away from the rapidly frosting window pane and back to the pot on the stove. He removed the lid and stirred the stew with a large wooden spoon. The venison was from a whitetail deer Harrison had shot a few weeks ago.

He looked down into the pot with distaste. Not that Benjamin didn’t enjoy venison—in fact, he loved it. But it was what it represented—right now, in this moment—that made him want to fling the pot of stew across the kitchen floor. The stew was just the latest in a series of efforts he had undertaken in order to stretch every cent they had. The more food they could grow or kill themselves cut down on the bill at the local supermarket, where food seemed to grow more expensive by the week.

He tasted the stew, added more salt, and glanced out the window again.

Over the past several months, he had tried to ignore the reality of their situation. But the truth was, the farm was in serious financial trouble. This was the third year in a row that they were barely squeaking by. For the first two years, crop and beef prices had been at an all-time low, which meant they had just covered their operating expenses. This past summer, a drought had wiped out a good portion of the area crops, which was both good news and bad. The drought had finally driven up corn and beef prices, and the farmers who had sufficient irrigation, or had been fortunate enough to catch a few extra summer thunderstorms, were rewarded with a nice profit.

But for the unfortunate ones, such as the Zimmerman brothers, the drought had decimated what little hope they had of turning a profit. By August, the fields had turned brown and the cattle were starving. They were forced to sell most of them at a loss, because the drought had driven up feed prices as well, making the option of purchasing food on the open market unacceptable. They had been able to keep only twenty head through the winter. To make matters worse, the crop insurance they carried on the farm had scarcely covered their expenses and left little to live on.

They were almost two years behind on the property taxes, and the county was threatening to take the only place they had ever lived. The thought of losing the farm almost drove Benjamin to madness daily. It had become all he thought about. Worry and stress had become his constant companions. They were with him when he woke in the morning and still there when he crawled into bed at night.

The fact was, they were not even squeaking by anymore. They were drowning. If something didn’t change soon, they would lose the farm—and Benjamin knew it.

His brother was a different story, though.

Harrison lived in a world of perpetual denial, and he didn’t seem to be worried about the prospect of losing the farm at all. Sometimes Benjamin wondered if his brother even cared. Harrison never had loved the farm like Benjamin did—that was obvious. Maybe he would be happy to have the county take the farm, and then he would be free to move on. He had often talked about selling the farm and moving somewhere warm. Maybe losing their home was Harrison’s way of hastening his retirement from farming.

Benjamin took two large bowls from the cupboard and filled them with generous servings of the venison stew. He topped each bowl of stew with two of the fresh biscuits and then carried both bowls to the small dining table that sat in the nook just to the right of the kitchen. The dining area was barely big enough to contain the small wooden table. The rectangular table had four place settings, two on the sides and one on each end. The two brothers always sat at the ends of the table. The side chairs were reserved for guests, which they rarely had. The last person to sit at the table other than Benjamin and Harrison had been a distant cousin from Texas who had driven up to hunt deer about five years ago.

Benjamin returned to the kitchen and retrieved two glasses of milk, utensils, and some napkins. Just as he was placing the remaining items on the table, Harrison opened the front door and walked in.

“Whew! Man, it’s cold outside,” he announced boisterously. “Wind must be blowing thirty or forty miles an hour already. Snow’s really coming down, too.”

Benjamin looked up from the table. “Glad you’re back. I was starting to get worried. Everything go alright?”

“Yeah, no problems.” Harrison dusted the snow off his hat and coat, then removed both and hung them on the coat rack that stood next to the front door. Snow had crept in below the edge of his hat and dusted his hair, exaggerating the salt and pepper color that the brothers now shared.

“How is the new calf doing?” Benjamin asked.

“Doing well, I think. Seems to be eating plenty, and she’s up and walking around now.”

One of the cows had given birth two days ago, and it had been touch and go for a while. They had been unsure if the calf would survive, so they had called the local veterinarian to come and assist them—another bill they could not afford.

“That’s good,” Benjamin replied as he folded two of the napkins and placed one under the edge of each bowl. “Dinner’s ready.”

“Thanks. It smells great.” Harrison removed his boots, and then walked down the long hallway that connected two of the bedrooms and the bathroom to the living room and kitchen. He opened the door to the bathroom and washed his hands and face in the sink. He reemerged a minute later, pulled his chair back from the table, and sat down. He always sat at the end of the table closest to the front door. Benjamin always sat with his back to the kitchen.

Both brothers bowed their heads for a moment in silent prayer—a habit their mother instilled in them and insisted on with the religious fervor of a traveling evangelist. Even after she died, they could not give it up, although Harrison had once made the suggestion—but Benjamin had rejected it.

“You did a good job with the stew…tastes great,” Harrison said as he took his first bite.

“Thanks,” Benjamin replied as he dipped one of the biscuits in the broth and took a bite himself. As much as he disliked what the stew represented, he had to admit it did taste good.

Both brothers continued to eat in silence for several minutes. Finally, Harrison spoke, “How much snow are they predicting with this storm?”

Benjamin knew the question was just Harrison’s attempt to keep the conversation going. Both brothers had watched the same weather forecast last night, just as they did every night before retiring to bed. “Twelve to fourteen inches…same as last night,” he responded.

“Oh…thought maybe they had changed the forecast today.”

“Not that I’ve heard.”

Silence.

Benjamin didn’t intend to be so stand-offish toward his brother. But when he became overly stressed, his habit was to withdraw. The pressure of possibly losing the farm had been mounting for the last three years, and he knew Harrison did not want to hear about his anxieties.

Family farming had always been—probably always would be—a zero-sum game. You certainly were not going to become wealthy doing it. At the very best, you could provide a comfortable income for yourself and your family. Most years were average and you made enough profit to keep the operation going. Sure, there had always been down years when things were on the brink, financially speaking, but a really good year would always come along and even everything out.

Not this time though. Even if they had a great crop and market prices remained high, they still would not have enough money to cover the operating costs and pay the property taxes off, not to mention living expenses. At least Benjamin had no wife or children to support, which relieved a worry that other area farmers had, but it also made his failure at farming even more profound. He couldn’t even make enough money to support his own meager existence.