A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (113 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Grant ordered a second charge, but many of the troops were done with fighting. The 69th was drunk before the attack—Pendlebury wandered forward in a daze, thinking he would dodge Confederate bullets if they came—and the men were captured en masse.

12

The Confederates were no less shaken by the six weeks of relentless fighting. Francis Dawson had suffered so many near misses that he was certain the next bullet would find him.

13

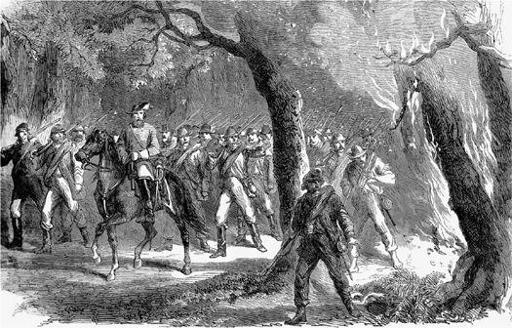

But his spirits had recovered since the return of Lawley and Vizetelly, who ran the blockade at Wilmington together on June 5. Vizetelly had brought with him a letter from Dawson’s mother. “Little did I think, when years ago, I saw drawings and sketches in the [London] Illustrated by our ‘special artist F. Vizetelli,’ or even when we had many a frolic together in the mountains of Tennessee,” Dawson wrote home on June 26, “that he, the same joyous, corpulent artist would have proved a source of such happiness to my dear parents and myself.” Dawson’s happiness was complete after Vizetelly drew a picture of his corps on a midnight march through burning woods.

14

“I am satisfied General Grant will make no more onslaughts upon the Confederate breastworks,” Lawley wrote from Lee’s headquarters on June 27. “Weeks and weeks will probably pass without amending Grant’s prospects before Petersburg.” The Confederates’ defenses stretched for over thirty miles in a protective semicircle of trenches and bombproof shelters, connected by walkways that in some places were six feet deep and up to twelve feet wide. Lawley recognized that the real danger to the Confederacy came from Sherman in Georgia. Only Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston and the Army of Tennessee stood between Sherman and Atlanta, the last strategic target of the South. The great question on Lawley’s, indeed everyone’s, mind was whether the Northern electorate would decide to end the war before Sherman reached Virginia.

Ill.51

A corps of the Confederate army marching by night through burning woods, by Frank Vizetelly.

Ill.52

View of Petersburg from General Lee’s headquarters—watching the Federals through binoculars, by Frank Vizetelly.

Three days later, on July 1, Lee’s artillery commander, General Edward Porter Alexander, arrived at the Confederate headquarters with disturbing news. He had seen activity that convinced him the Federals were digging a tunnel under the trenches. Lawley asked him how long it would have to be to clear their works: “I answered about 500 feet,” Alexander recalled. “[Lawley] stated that the longest military tunnel or gallery which had ever been run was at the siege of Delhi, and that it did not exceed 400 feet. That it was found impossible to ventilate far greater distance.” Alexander reminded him that the average coal mine went much farther and it would not be too taxing for the Federals to ask any volunteer from the Pennsylvania mines about ventilation. Lee had no option but to wait and see who would turn out to be right.

15

Lawley and Vizetelly suffered as the summer heat cast a pall over the trenches. To pass the time, Vizetelly drew portraits of Lee and his staff watching the Federals through field glasses. The biggest excitement was the arrival of a captain from the British Army, G. T. Peacocke, who reported to duty as a volunteer aide to General Pickett.

16

Lawley filled his reports with stories of “African savagery” and Federal brutality toward women and children, but he neglected to describe the hunger that now afflicted Lee’s army. One of the more colorful English blockade runners, the Hon. Augustus Charles Hobart-Hampden, the third son of the Earl of Buckinghamshire, whose later exploits with the Turkish navy won him the title “Hobart Pasha,” visited the front lines in July. He came armed with boxes of sausages and sardines, which were eagerly gobbled up by the grateful Confederates. “For months past [they] had tasted nothing but coarse rye-bread and pork washed down with water,” wrote Hobart-Hampden. “There were several Englishmen among the officers composing the staff,” he added with surprise. “I often wonder what has become of them.”

17

Hobart-Hampden saw Petersburg and Richmond, where nearly every other female was dressed in deep mourning, and even snatched a half-hour conversation with Lee himself, yet still he believed Lawley’s optimistic prediction of Southern victory. “Though a line of earthworks hurriedly thrown up in a few hours at Petersburg was nearly all that kept Grant’s well-organized army from entering the capital; though the necessaries of war, and even of life, were growing alarmingly short,” he wrote after the war, “still everyone seemed satisfied that the South would somehow or other gain the day.” Lawley he could excuse, since the journalist was “so carried away by his admiration of the wonderful pluck shown by the Southerners … whereas all of us … should have seen the end coming months before we were obliged to open our eyes to the fact it was come.”

18

The Welsh army veterinarian Griffith Evans had obtained an observer’s pass from the Medical Department and was visiting the Federal lines at the same time that Hobart-Hampden was with the Confederates. He, too, had little sense that the South was struggling when he arrived at Petersburg. His first visit was to General Butler’s camp on July 3, where the flies were already a pestilence. (They were the biting kind and “are very troublesome indeed,” James Horrocks complained to his brother.)

19

All day long, wrote Evans, the men sat in their fetid dugouts, sweltering in the heat, until the night shift relieved them. It was a dreadful existence, and he pitied them. Soldiers talked to him about the “fearful slaughtering” they had witnessed in vague tones, “as if they wished to forget it.”

Driving around the countryside, Evans thought he had never beheld anything so hideous, so redolent of biblical destruction: “Fences pulled down for fuel, the crops in the fields trodden down, houses deserted or occupied by troops, or burnt down, thousands of recent graves of men killed or died lately, and those so shallow that the stench from them was in places intolerable. Dead cattle and horses, men’s accoutrements, etc., strewn about, etc. etc. It was indescribable and the effect was sad and sickening.”

20

He could not imagine how the soldiers would tolerate their conditions for much longer.

A rumor was spreading through the camps during Evans’s visit. The army discouraged discussion of it, but the news eventually leaked out. Sir Percy Wyndham had ridden into the camp of the 1st New Jersey Cavaliers insisting that he was once more their colonel. Although the men knew that the New Jersey state legislature had petitioned Washington for Wyndham’s reinstatement for the second time on June 4, there had been no indication that Stanton had changed his mind. After a tense standoff, the lieutenant colonel of the regiment ordered the arrest of Wyndham, who refused to leave quietly. Wyndham created such an uproar that General Meade had him escorted to Washington under guard on July 1. His discharge papers were waiting for him when he arrived. On July 5, 1864, Sir Percy Wyndham was officially mustered out of the army, and strongly encouraged to leave town.

30.1

Griffith Evans’s own return to Washington was impeded by a Confederate raid on the perimeter. The audacious attack led by Jubal Early was an attempt by Lee to force Grant into detaching part of his army to defend Washington. “There is a large Confederate force within three or four miles of Washington, and some perhaps think they will make an attempt to take the town today,” Lord Lyons informed his sister on July 13. But though there was panic in the city, the legation was not even bothering to pack up the archives. “Even if the town was taken my physical comfort would not be likely to be disturbed,” Lyons decided. “I don’t really expect to have to move, and I daresay you will hear next week that things have lapsed into their odious condition.”

Lyons was far more worried about the state of his staff. He repeatedly told the Foreign Office that it could no longer assign the same number of attachés to Washington as it did to Ulan Bator. The secretary, William Stuart, and one of the junior staff had left before the arrival of their replacements. “The heat is overpowering,” Lyons wrote to Lord Russell. “I am anxiously looking out for [their] arrival … and I hope they will be immediately followed, if they are not accompanied, by one or more Third Secretaries or Attachés—otherwise the whole Legation will be knocked up.”

21

A letter from Joseph Burnley, the new secretary, brought terrible news: he was coming out with his wife and children. “A dreadful prospect for me—and still worse for him, poor man,” wrote Lyons. No woman had disturbed the monastic peace of the legation for the past five years.

22

Lyons set about trying to dissuade Burnley from bringing his family. He could, with complete honesty, describe the lonely existence of a British diplomat in Washington. With Henri Mercier gone, and the Russian minister, Baron Stoeckl, on leave for the summer, Lyons had received not a single invitation to dinner for weeks.

23

Griffith Evans was concerned for Lyons when he visited the legation on July 20, though the minister sheepishly declined his sympathy. Evans should reserve his pity for the country’s leaders, Lyons told him: “Mr. Lincoln is not the man to look at that he was four years ago.” The Welshman realized the truth of this statement when he visited the White House a few days later. He walked through the “Grand Reception Room,” which he thought was “very seedy looking,” into Lincoln’s office without anyone’s challenging his presence. Lincoln was so exhausted and put upon that he did not think to ask why a stranger was in his office. “He shows marks of mental overwork,” decided Evans after a few minutes’ conversation.

24

The pressures on Lincoln were increasing. Grant’s failure to capture Richmond and Jubal Early’s raid near Washington had shaken the cabinet’s confidence. The tense divisions between the members resurfaced in violent quarrels and a resumption of the old plots and counterplots against one another. Seward, whose son Will had been wounded while defending Washington against Early, turned some of his frustration on Lord Lyons. He rudely dismissed as exaggeration the minister’s complaints that the Central Guard House in Washington was using water punishments against alleged deserters. Lyons had evidence from six separate cases, and he was outraged by the State Department’s explanation that a cold shower was pleasant in the summer. Turning water cannons on prisoners was not “in conformity with any law or regulations,” he bluntly wrote to Seward on July 25. It was used for one reason only: “for the purpose of extorting, by the infliction of bodily pain, confessions from persons suspected of being deserters.”

25

Nor was this his only complaint against the army. That same week, Lyons received evidence from the New York consulate of British subjects being hung by their thumbs until they agreed to sign confessions of desertion.

The legation’s only success in July was the rescue of Admiral Usher’s grandson, Henry, who had walked into the New York consulate on the thirteenth, painfully thin and unsteady on his feet. “Usher has been for about a week in hospital in this place, too ill to report to me until today,” recounted the deputy consul. Now that they had him, they were not allowing him out of their sight. One of the clerks went to the ticket office to purchase a berth for the boy, and another stayed by him until he boarded the steamer. The attachés celebrated the news that young Usher had departed from New York by having a drink at Willard’s.