A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (120 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

On September 11, rumors reached London that Sherman had captured Atlanta. The effect on the legation was electric, even though they had to wait a full week before receiving confirmation of the news. The reports were “doubted by

The Times

and disbelieved in the City,” Henry told his brother Charles. For the past month the press had been castigating Lincoln for his refusal to concede defeat. Even William Howard Russell had written in the

Army and Navy Gazette:

“The Northerners have, indeed, lost the day solely owing to the want of average ability in their leaders in the field.”

37

The Confederates and their supporters tried to play down the strategic importance of Atlanta. Slidell assured the French emperor during a chance conversation at the races that Sherman’s latest advance would be a pyrrhic victory for his overstretched and undersupplied forces. The emperor “expressed his admiration and astonishment at what we had achieved,” the commissioner reported to Benjamin. But, he added bitterly: “A year ago I should have attached some important political signification to this incident.”

38

Knowing that Atlanta’s fall would boost the chances of Lincoln’s winning a second term, Hotze hastened his departure for Germany: “It is from Germany that the enemy must next spring recruit another army,” he wrote. “It is upon Germany that he relies for the gold to carry on the war.”

39

Georgiana Walker and her family also left England. Her husband, Norman, had joined them at the end of August, driven from Bermuda by an outbreak of yellow fever. The Confederates agreed that he should make Halifax, Nova Scotia, his new base for supplying the South until it was safe to return to the Caribbean. On September 30 the family set sail for Canada on the

Europa.

The chief drawback to the voyage, wrote Georgiana, was the number of “Yankee” passengers. “But I must admit that they behaved themselves as well as Yankees can behave and exhibited that respect for us, which all Yankees feel for Southerners.”

40

She was expecting to be miserable in Halifax until she remembered that Rose Greenhow might still be there, waiting for a blockade runner to take her to Wilmington. The thought of being with her friend gave Georgiana hope that everything would turn out well.

32.1

Rose was not alone in feeling guilty about her comfortable life in Britain. When Matthew Fontaine Maury read that the birthday present of his youngest child was to be allowed to eat until full, he confessed to Francis Tremlett that he “felt as if I must choke with the sumptuous viands set before me on the Duke [of Buckingham]’s table.”

15

32.2

The holiday had been a trial: Henry did not mind his brother-in-law, Charles Kuhn, but his sister Loo had turned into a peevish invalid. Rather like Alice James, the intelligent, thwarted sister of Henry and William James, Loo was too wealthy to have an occupation and too clever to be happy without a purpose other than herself. “She is evidently much bored by our life,” Henry commented drily to Charles Francis Jr.

THIRTY-THREE

“Come Retribution”

Burley and Beall are reunited—Lord Lyons meets Feo—Shipwreck—Charleston under siege—Northern ambivalence—The enemy in ashes

L

ord Lyons arrived in Montreal on September 15, 1864, with his two favorite attachés, George Sheffield and Edward Malet. Simply being away from the unhealthy climate of Washington was enough to restore Malet’s health: “A change of air is all I wanted,” he informed his mother, “and I now feel as if I had never been ill.”

1

But Lyons, he noticed, remained weighed down by his fear that many tedious discussions awaited him in Quebec about Federal crimping and Confederate plots.

The governor-general of Canada, Viscount Monck, was in many ways as isolated as Lord Lyons. Though blessed with a genial manner and patrician ease at social gatherings, Monck’s determination to avoid showing favoritism toward any party forced him to maintain a degree of aloofness from the Canadians, who could sense that he looked askance at their internal quarrels. Monck thought his ministers were among the most small-minded men he had ever encountered. None of them, he wrote in a confidential letter to London, “is capable of rising above the level of a parish politician.”

2

It had been clear to him since his arrival three years earlier that the endemic suspicion and jealousy between Canada’s provinces had been disastrous for the country’s development. To survive and flourish, Monck believed, these separate provinces had to be persuaded that their future prosperity depended upon confederation; and he had thrown himself into the project with energetic zeal.

33.1

He hoped that at the very least, political unity would strengthen Canada’s relations with the United States, and that it might possibly even make the colonists more willing to pay for their own defense—an object dear to London.

Lord Monck had been concerned about Southern violations of British neutrality ever since the Confederate agents had appeared in the spring, petitioning—without success—to have five additional ships sent to patrol the Great Lakes. Personally, he was pro-Northern rather than neutral (or even pro-Southern like many Canadians), and was doing his best to discourage the Confederacy from sending its agents to Canada. In November 1863 he had foiled a Southern plot to attack the Federal prison camp on Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie off Sandusky, Ohio—successfully, though only temporarily, dampening the Confederates’ interest in launching raids from Canada against the North.

3

During the summer, Commissioner Jacob Thompson had revived the plan to liberate the prisoners on Johnson’s Island. The days when almost any force could have taken the island were long past, but the prison was still an enticing prospect for the Confederates because its position in Sandusky Bay was close to the Canadian border. Sandusky itself was a minor town; Charles Dickens had paid a fleeting visit in 1842 and thought the place bleak and the population “morose, sullen, clownish and repulsive.”

4

But to the fugitive slaves who escaped captivity via the “underground railroad” to Canada, Sandusky represented their last stop before freedom. The U.S. authorities had chosen Johnson’s Island for the opposite reason; without a boat, it was the last stop to nowhere.

The island’s prison was badly built and poorly maintained: its latrines lacked drainage and the barracks had no running water. But the suffering of the 2,500 Confederate prisoners had only really begun in the spring, when the War Department decreed that conditions should mirror those of Southern prisons; food parcels were confiscated, and prisoners were forbidden to supplement their rations except by capturing rats (which were, however, plentiful). These weak and diseased inmates were the men Jacob Thompson intended to use to bring terror to the United States’ northern border.

The iron-hulled gunboat USS

Michigan

had been patrolling Sandusky Bay since Monck’s exposure of the first Confederate plot against Johnson’s Island. Before then, it had been employed to make draft protesters in Detroit think twice before they rioted.

5

The warship had never fired its guns and was too unseaworthy for deployment in battle, but since she was the only naval vessel on Lake Erie, whoever sailed her controlled the lake. In mid-July, Thompson believed he had found the right man to capture the vessel.

Twenty-seven-year-old Charles H. Cole was a mystery to everyone who knew him. He lied about his war record, hiding the fact he had been cashiered from the Confederate army in 1863 for dishonesty.

6

He had never held a leadership role, and yet in July he managed to dupe Thompson into giving him $4,000 to investigate the various possibilities for seizing the

Michigan.

7

Cole used the money to treat his girlfriend to a luxurious holiday tour around the Great Lakes before finally settling down to business on August 11 and booking a room for “Mr. and Mrs. Cole” in one of Sandusky’s better hotels. The West House overlooked Sandusky Bay, offering its clientele an unobstructed view of Johnson’s Island and USS

Michigan,

which was usually anchored nearby. Cole’s reports to Thompson were sufficiently optimistic to elicit the order that he should spend whatever it took to bribe the officers or purchase the

Michigan

outright. “He thinks everything looks favourable and is sanguine of success,” Thompson told Clement Clay on August 13, 1864. Cole opened an account in one of the local banks, letting it be known that he represented an oil company from Pennsylvania, and began distributing his largesse among the

Michigan

’s officers. None responded to his cautious overtures. Even the captain, John C. Carter, who resented sailing around an empty lake while his peers were off chasing Confederate raiders, was beyond reach.

Cole wrote to Thompson in August telling him that he was ready to lead a team of Confederates to capture the vessel. The claim may have been nothing more than a maneuver to gain more time and funds. If so, he was caught out when Thompson not only ordered him to proceed but also sent him one of his best volunteers, John Yates Beall, late of Chesapeake Bay.

8

Once he met Beall, Cole realized that his comfortable little setup was at an end. Beall had crossed into Canada hoping to start his own privateering operations on the Great Lakes, but he dropped the idea after hearing about the Johnson’s Island plan from Thompson. “I immediately volunteered,” wrote Beall, “and went to Sandusky, Ohio, to meet Captain Cole, the leader. We arranged our plans, and separated. Cole stayed at Sandusky. I came to Windsor to collect men, and carry them to the given point.”

9

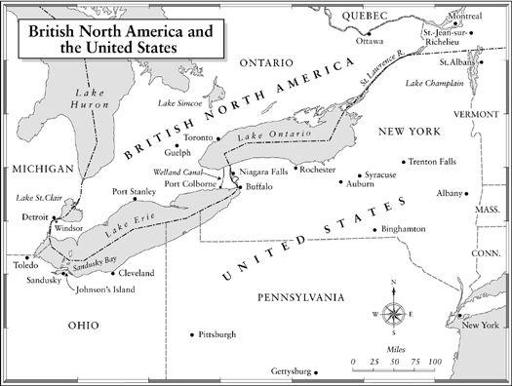

Map.20

British North America and the United States

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Beall remained in Windsor until the beginning of September, carefully working out the details of the plan with Thompson. He was overjoyed when Bennet G. Burley arrived after a difficult journey through the North. Burley’s British nationality meant he could purchase the equipment and weapons required without inviting suspicion, and Cole’s role was gradually reduced until his sole contribution was to arrange an evening of diversions for the

Michigan

’s crew.

10

Some were to be entertained on shore, the rest plied with drink on the vessel. While Cole was intoxicating the crew, Beall and his team were to capture the local Sandusky ferryboat called the

Philo Parsons

and, on Cole’s signal, to sail alongside the

Michigan

and climb aboard. Then, with the element of surprise on their side, they would fire on the garrison guarding Johnson’s Island, blow open the walls, and release the prisoners.

On September 17, two days before the date appointed for the raid, one of Beall’s volunteers betrayed the group to the provost marshal of Detroit. Captain Carter of the

Michigan

was initially skeptical of the report, until he remembered that Cole had arranged a party for the

Michigan

’s crew at an inn on the outskirts of Sandusky. On the morning of the nineteenth, Carter sent a trusted officer to the West House hotel, who lured Cole onto the

Michigan

on the pretext of asking permission for the entire crew to attend the party. As soon as he was on the vessel, Cole was arrested and searched for papers. The documents Cole was carrying were not particularly revealing, but that did not stop him from confessing everything to Captain Carter. He also admitted that he had intended to abscond with Thompson’s money before carrying out the final part of the plan: to rescue the prisoners.

11

In the meantime, Beall and Burley had boarded the

Philo Parsons,

fully confident that Johnson’s Island would be theirs by midnight. Burley persuaded the ferry captain to make an unscheduled stop at Sandwich, on the Canadian side of the river, to pick up three friends, one of whom he said was disabled; the ship’s clerk noticed that the disabled man was miraculously cured as soon as the vessel started moving again. At the next stop, another sixteen men climbed aboard, bringing a large wooden trunk with them. The

Philo Parsons

continued chugging quietly along its scheduled route until 4:00

P.M.,

when the trunk was opened and Burley handed out two dozen revolvers and hatchets. Within half an hour, all the passengers and crew were locked in the cabin. No one was hurt, although a few shots had been fired.