A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (142 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Rossetti concluded his essay about Britain and the American Civil War with an apology that speaks for all those authors who venture into this complex history: “For anything I have said which may possibly sound egotistic or intrusive—still more for anything erroneous or unfair in my statements or point of view—I must commit myself to the candid construction of my reader, be he [or she] American or English.”

47

epl.1

The poet Algernon Swinburne also became friends with Feilden. “I defy you not to like him if you knew him,” Swinburne wrote to a friend in 1867. “[He is] one of the nicest fellows alive, and open as such men should be, to admiration of all fallen causes and exiled leaders. I am not saying they are equal in worth—heaven forbid—only I must say that failure is irresistibly attractive, admitting as I do the heroism of the North.”

epl.2

The

Shenandoah

had been at sea for a year when Captain Waddell finally brought her back to England, six months after the war’s end. During that time the cruiser had captured thirty-eight ships, the majority of them Northern whalers, and taken more than a thousand prisoners. Waddell had believed that the South would continue to fight after Lee’s surrender. It was the capture of President Davis—which he learned from the British bark

Barracouta

on August 2, 1865—that persuaded him to surrender, too.

epl.3

As a veteran of the Federal army, Prince Salm-Salm was almost unique among the 2,500 Americans who immigrated to Mexico after the Civil War. The exodus of ex-Confederates was orchestrated by Matthew Fontaine Maury, who offered his services to Emperor Maximilian in June 1865 and was appointed imperial commissioner of immigration. Most settled near Cordoba in a specially designated area known as the Carlotta Colony, where they eked out a miserable existence for a couple of years before returning to the South. Another nine thousand Southerners moved to Brazil, where slavery remained legal, and about a thousand went to British Honduras, now Belize. The community at Forest Home in Punta Gorda died out, and its cemetery is now a tourist attraction.

epl.4

In late March 1865, President Lincoln had discussed the

Trent

affair with General Grant, making it clear that Britain deserved to be punished: “We gave due consideration to the case, but at that critical period of the war it was soon decided to deliver up the prisoners. It was a pretty bitter pill to swallow, but I contented myself with believing that England’s triumph in the matter would be short-lived, and that after ending our war successfully we would be so powerful that we could call her to account for all the embarrassments she had inflicted upon us.”

36

epl.5

Britain actually paid out $8,070,181, since the United States agreed to give Canada $5.5 million for the right to fish in its waters and also paid $1,929,812 in compensation as a result of rulings at the mixed commission on British and American claims.

1.

Richard Bickerton Pemell Lyons, 2nd Lord Lyons (1817–87). Lyons arrived at the British legation in the spring of 1859 and stayed until December 1864, when he returned to England, having worked himself to exhaustion.

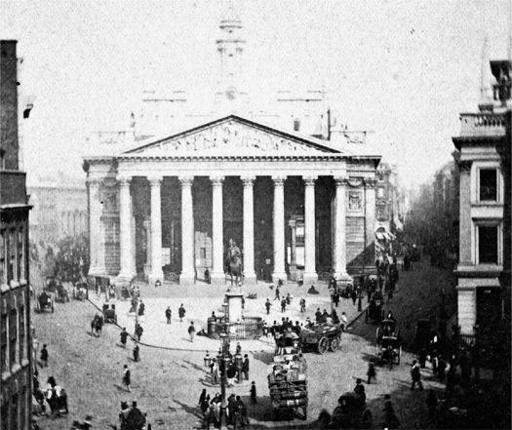

2.

The British legation at Rush House, 1710 H Street, Washington.

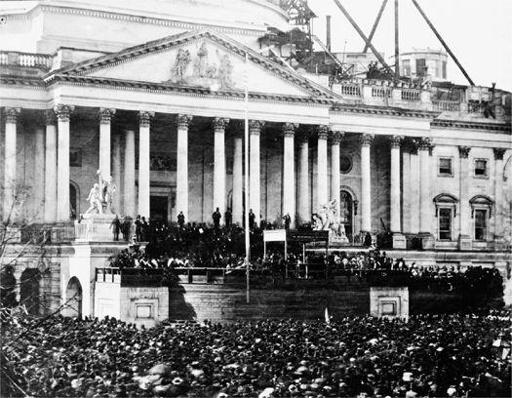

3.

The U.S. Capitol, Washington. Charles Dickens visited the capital in 1842 and thought the city had “Magnificent Intentions,” with “streets [a] mile long, that only want houses, roads, and inhabitants.” Fifteen years later, these intentions remained unfulfilled. A disagreement between the U.S. Federal government and a local landowner had stranded the unfinished Capitol building on top of a steep hill at the edge of town, facing the wrong way. The dome was finally completed on December 2, 1863.

4.

President Lincoln’s inauguration in front of the incomplete Capitol on March 4, 1861. In his inauguration speech, Lincoln tried to reassure the Southern states about his intentions toward slavery, but by then it was too late to stem the tide of secession: the war began six weeks later.

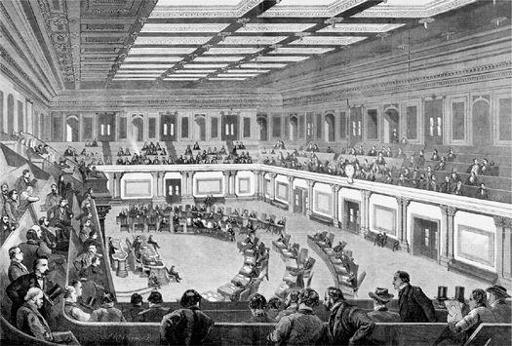

5.

The U.S. Senate. Here, on May 22, 1856, Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina ambushed Senator Charles Sumner, who was sitting at his desk reading, and beat him with his cane. By Brooks’s own account, he struck Sumner thirty times before the cane splintered.

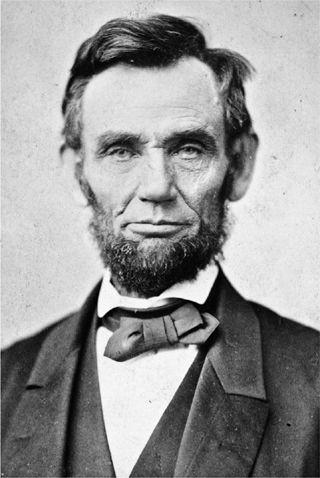

6.

President Abraham Lincoln (1809–65). Lincoln’s physical appearance astonished people. The British journalist William Howard Russell was introduced to him at around the time this photograph was taken in 1861: “There entered, with a shambling, loose, irregular, almost unsteady gait, a tall, lank, lean man, considerably over six feet in height, with stooping shoulders, long pendulous arms, terminating in hands of extraordinary dimensions which, however, were far exceeded in proportion by his feet. He was dressed in an ill-fitting wrinkled suit of black, which put one in mind of an undertaker’s uniform at a funeral.” By the end of the war, the world saw past Lincoln’s appearance to his humanity and magnanimity toward his foes.

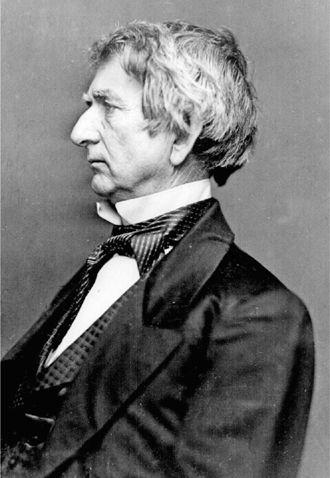

7.

William Seward (1801–72), U.S. secretary of state, Lincoln’s rival for power before the war but who became his greatest ally during it. Seward’s frequent statements that Canada would one day belong to the United States, coupled with his unscrupulous playing to American Anglophobia, made him the most detested U.S. politician in Britain.