A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (61 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Ill.26

As the French and British governments ponder intervention, Punch argues the time is now.

Lord Palmerston reacted to the two announcements with a far cooler head than either Russell or Gladstone. All along he had been a proponent of mediation while the outcome of the war seemed obvious. But Lee’s check at Antietam, regardless of his miraculous escape across the Potomac, had revealed a serious weakness in the Confederate army. The prime minister’s confidence in the mediation plan was further shaken by a strong remonstrance from Lord Granville, the Liberal leader in the House of Lords, who argued in a letter to Russell on September 27 that any sort of interference in the war—no matter how good or charitable the intention—would only result in Britain becoming dragged into the conflict. “I return you Granville’s letter which contains much deserving of serious consideration,” Palmerston wrote to Russell on October 2. “The whole matter is full of difficulty, and can only be cleared up by some more decided events between the contending armies.”

8

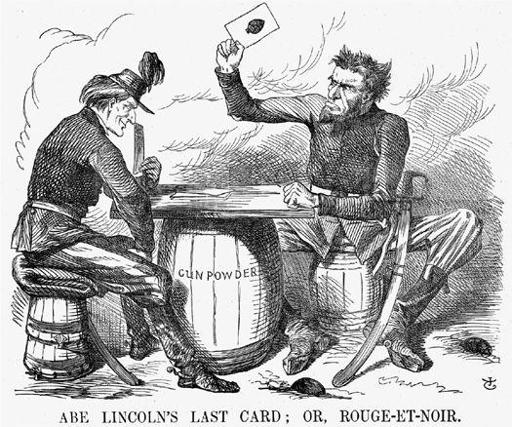

Ill.27

Punch portrays Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation as a last desperate move.

Russell had come to the opposite conclusion. He wanted the cabinet meeting to discuss mediation brought forward by a week, from October 23 to the sixteenth. The news of Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation had convinced him that only Britain had the power to stop the humanitarian crisis unfolding in America. The answer to Granville’s objections, he thought, was to build an international alliance involving France and Russia to force the warring sides to agree to an armistice. “My only doubt is whether we and France should stir if Russia holds back,” he told Palmerston.

9

Gladstone was also moved by his belief that a humanitarian crisis was at hand, though he saw two—the one in Lancashire as well as the one in Virginia. Unlike Russell and Palmerston, he did not think that the Confederates had suffered a significant setback at Antietam. “It has long been clear enough,” he wrote, “that secession is virtually an established fact.” When Gladstone talked about the undecided questions in America, he meant whether “Virginia must be divided, and probably Tennessee likewise.”

10

He patiently brushed aside the Duchess of Sutherland’s objections, telling her that “Lincoln’s lawless proclamation” would be far more destructive to America than a separation between the states. When the duchess informed her son-in-law, the Duke of Argyll, about this latest twist to Gladstone’s view of the war, the duke sent him a blistering rebuke. “I would not interfere to stop [the war] on any account,” he wrote. “It is not our business to do so; and even short-sightedly, it is not our interest. Do you wish, if you could secure this result tomorrow, to see the great cotton system of the Southern States restored? Do you wish to see us almost entirely dependent on that system for the support of our Lancashire population? I do not.”

11

The combination of his worries about Lancashire and his disgust with the Emancipation Proclamation pushed Gladstone over the edge. On October 7, the day after the Proclamation appeared in

The Times,

he went to Newcastle to attend a banquet in his honor. He had been thinking all day about “what I should say about Lancashire and America: for both these subjects are critical.”

12

Gladstone later told his wife that the acoustics were terrible and he had struggled to make himself heard. It would have been better for him, perhaps, if he had not been heard at all. The words that caught everyone’s attention were these: “We may have our own opinions about slavery; we may be for or against the South, but there is no doubt that Jefferson Davis and other leaders of the South have made an army; they are making, it appears, a navy; and they have made what is more difficult than either; they have made a nation.”

Gladstone’s startling announcement was telegraphed all over Europe almost before he had sat down. Ambrose Dudley Mann in Brussels wrote to Richmond that same night: “This clearly foreshadows our early recognition.”

13

Thirty-four years later, Gladstone admitted that his speech was a mistake of “incredible grossness.” “I really, though most strangely, believed that it was an act of friendliness to all America to recognize that the struggle was virtually at an end.” He hated to think of the damage he had caused, “because I have for the last five and twenty years received from the … people of America tokens of goodwill which could not fail to arouse my undying gratitude.”

14.1

14

But at the time he was unrepentant, until Russell pointed out to him that he had created a controversy where none had existed.

Benjamin Moran worked himself up into one of his customary rages after he read the morning news on October 8. Adams was not sure what to think. He knew enough about British politics now to realize that it would be highly unusual for a change in cabinet policy to be announced in this way. The press seemed hesitant as well. When Adams saw William Forster four days later, he revealed that Seward had given him secret instructions that he was to withdraw from his post if recognition or intervention became government policy. Forster thought this was something the Foreign Office ought to know before it made any irretrievable decisions. But, Adams wondered, was this the Foreign Office at work, or just Gladstone? Feeling depressed, he cheered himself up with a trip to the theater to see

Our American Cousin.

“The piece has no literary merit whatever,” he wrote. “I laughed heartily and felt better for it.”

16

It seemed to Adams that his question about the British cabinet’s intentions was answered a week later when Sir George Cornewall Lewis gave a speech in Hereford contradicting Gladstone’s claim that the South was an established nation. His speech received favorable comment in the North and caused uproar in the South. Gladstone’s “made a nation” remark was forgotten. Britain was the clear leader in Europe, complained the influential

Richmond Enquirer:

Lewis had extinguished the light and closed “the last prospect of European intervention.”

17

At home, a relieved Adams decided that Gladstone had spoken only for himself in Newcastle and “had overshot the mark.”

After these two conflicting statements, there were no more public comments by any of the cabinet. But furious arguments were taking place behind the scenes. Gladstone and Lewis had long been rivals. Only one of them could become Palmerston’s heir, and each was conscious of the other’s near presence. Allowing his emotions to cloud his judgment was exactly what the aloof and scholarly Lewis expected of Gladstone. Russell, whenever he thought that the liberal Whig traditions of the house of Bedford were at stake, did the same, and this, Lewis knew, was their weak point.

Russell issued a memorandum to the cabinet on October 13 that laid out why they should intervene and settle the war. Lewis pounced on it and wrote a scathing countermemorandum on the seventeenth, pointing out that it was not a debating club that would be receiving the mediation proposal but “heated and violent partisans,” who would reject it in an instant. The South would not be grateful for the help, thought Lewis, and the North would swear vengeance on Britain.

18

Many years later, Henry Adams decided that the real reason why the cabinet fell into such a muddle over the American question was because the English were, by habit, eccentric:

The English mind took naturally to rebellion—when foreign—and it felt particular confidence in the Southern Confederacy because of its combined attributes—foreign rebellion of English blood—which came nearer ideal eccentricity than could be reached by Poles, Hungarians, Italians or Frenchmen. All the English eccentrics rushed into the ranks of the rebel sympathizers, leaving few but well-balanced minds to attach themselves to the cause of the Union.… The “cranks” were all rebels.… The Church was rebel, but the dissenters were mostly with the Union. The universities were rebel, but the university men who enjoyed most public confidence—like Lord Granville, Sir George Cornewall Lewis, Lord Stanley, Sir George Grey—took infinite pains to be neutral for fear of being thought eccentric. To most observers, as well as to

The Times,

the

Morning Post,

and the

Standard,

a vast majority of the English people seemed to follow the professional eccentrics; even the emotional philanthropists took that direction … and did so for no reason except their eccentricity; but the “canny” Scots and Yorkshiremen were cautious.

19

Senior Tories also voiced their concerns after they discovered that Russell was on the verge of approaching the French with his intervention plan; the opposition still maintained its stance that Britain should avoid becoming entangled with either side. Lord Derby had no doubt, wrote Lord Clarendon, “we should only meet with an insolent rejection of our offer.”

20

But Russell was no longer listening to his critics. He had already made overtures to the emperor via the British ambassador in Paris, Lord Cowley. However, the French cabinet was undergoing one of its periodic crises, and the foreign minister was clearing his desk for his successor. The Confederate commissioner in Paris, John Slidell, was in a state of nervous excitement. By now, he wrote to the Confederate secretary of state, Judah P. Benjamin, on October 20, “I had hoped to have had it in my power to communicate something definite as to the Emperor’s intentions respecting our affairs.” Instead, everything seemed to be in confusion. Slidell’s informants were giving him conflicting accounts of the two countries’ intentions. All he knew for certain was that the emperor was their friend and that Lord Lyons most decidedly was not. Slidell ended his letter with the rueful admission: “I have no dispatches from you later than 15 April.”

21

It was mortifying to James Mason to hear that John Slidell was having another interview with the emperor. The Confederates in England envied Slidell for his easy access to senior French politicians. “I have seen none but Lord Russell,” Mason admitted to his wife, and that was “now nearly a year ago.”

22

Henry Hotze had to scavenge for news, seizing on scraps and tidbits from friends with “connections to high places” without ever quite knowing whether he was receiving supposition or fact. He was mesmerized by the unprecedented cabinet brawl over the recognition question. “This species of ex-parliamentary warfare was opened with the sparring between Mr. Roebuck and Lord Palmerston,” he wrote. “Since then it has grown more serious, and in the case of Mr. Gladstone and Sir George C. Lewis into almost open animosity.” In trying to divine the tea leaves, Hotze put great weight on the fact that Lord Lyons was still in London. He hoped it meant that the cabinet was teetering on the side of the South. He tried giving a gentle shove toward Southern recognition by encouraging his “allies in the London press” to increase their output. Some writers, including one at the Tory-leaning

Herald,

were even willing to let Hotze dictate their articles. There was, however, one person whom Hotze wished he could silence. “I almost dread the direction his friendship and devotion seem about to take,” he confessed. James Spence had been inspired by the Emancipation Proclamation and was now convinced that the South should issue one of her own. Hotze was furious with Spence for bringing the subject into public view again, but he was at a loss how to divert him.

23

Mason was encountering a similar problem from his friends in the Tory Party, who were trying to extract a pledge from him that the South would renounce slavery.

Hotze’s fears that the slavery question might prevent recognition were allayed after he learned that the cabinet meeting and Lyons’s departure had again been delayed. This, he thought, was proof that intervention was imminent. In fact, the meeting of October 23 had not been so much delayed as sabotaged. Palmerston had become alarmed by Russell’s apparently blind enthusiasm for the mediation plan. “I am very much come back to our original view of the matter, that we must continue merely to be lookers-on till the war shall have taken a more decided turn,” he told Russell on October 22. Rather than argue with Russell face-to-face, Palmerston stayed away from the cabinet meeting, which meant that nothing official could be decided. The members who did turn up argued heatedly with Russell and Gladstone, both of whom were so shaken by the experience that each afterward wrote detailed defenses of his position. Russell was especially upset with Lewis, whose memorandum had made him look foolish. The document accused him of propositions “which I never thought of making,” Russell wrote grumpily to Palmerston.

24

He was beginning to feel cornered. A visit from Charles Francis Adams on the same day as the aborted cabinet meeting only served to increase his discomfort.