A Writer at War (34 page)

Authors: Vasily Grossman

In Starobelsk, he encountered strange echoes of the pre-revolutionary past.

I gave a lift in my truck to a priest, his daughter and granddaughter, with all their belongings. They received me [at home] as if I were royalty, with a supper and vodka. The priest told me that Red Army soldiers and officers come to him to pray and to talk. One major came to see him not long ago.

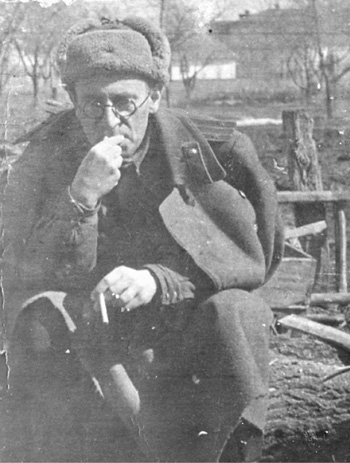

Grossman at the headquarters in Svatovo, April 1943.

Story about the Tsar’s sister Kseniya, who lives in Starobelsk. She had protected Soviet people from the Germans. People say that she had returned from abroad with Dzerzhinsky’s permission some time ago, in order to find her son.

1

This is a complete myth. The Grand Duchess, who had left the Crimea in 1919 with the Dowager Empress and other members of the imperial family on board the battleship HMS

Marlborough

, never returned to Russia. During the Second World War she was living at Balmoral, not in Starobelsk.

An attempt to fish, [but] a Messer attacked suddenly, firing at us.

The Ukrainian government has accommodated itself on a scrap of liberated Ukrainian land, in the tiny town of Starobelsk, in a tiny white building. A talk with Bazhan.

2

He complained about our great-power chauvinism. A guard standing at his door has one of those inhuman faces that takes one back immediately to the time of peace.

A war correspondent, the Ukrainian writer Levada, is terribly upset because he has been given a medal instead of a [military] order.

3

After receiving it, he returned to the

izba

where he was based. A little girl shouted, looking at the medal: ‘A kopeck!’ The boy corrected her: ‘That isn’t a kopeck, you fool, that’s a badge.’ This was the last straw for Levada.

Starobelsk had been occupied by remnants of the Eighth Italian Army after it was shattered on the Don by Operation Little Saturn in the second half of December.

People, especially women, speak well of the Italians. ‘They sing, they play, “O mia donna!”’ However, people disapprove of them for eating frogs.

How agonising, how alarming this lull at the front is! There’s already dust on the roads.

The rainy period of deep mud, the

rasputitsa

, was over, as the dust showed, which indicated that the ground was already hard enough for all vehicles, yet nothing had happened.

Grossman interviewed General Belov.

4

‘A German division’s area of responsibility is eight kilometres deep. If we break through to a depth of eight kilometres, we will paralyse the front to a depth of thirty kilometres. If we break through thirty kilometres, we would paralyse a hundred kilometres. If we break through a hundred kilometres, we would paralyse the command [and control] of the whole front.

‘We made one mistake on the Don: I was told that the men were tired. I lost two hours while they rested, and the [Luftwaffe] had the opportunity to attack and [the German ground forces] pulled in their reserves. If we hadn’t had that rest, we would have made it. One must act boldly. If you look over your shoulder, you get squashed.

‘There are commanders who show off: “I am facing the [enemy’s] fire. I’ve halted, I am carrying out reconnaissance.” What nonsense! What else can you face? Of course [it’s going to be] fire. Are they going to throw apples at you, or what? You must break through even more deeply and suppress their fire. The deeper you break through, the weaker and more confused the enemy will be . . . Yet both in the battle and in the whole operation there’s a moment when one should think things over, whether to rush forward, throw all your reserves into fighting, or, on the contrary, to stop. Our commanders sometimes love ordering: “Forward, forward!”

‘There should be an operational pause, after about five days, when you’ve run out of all ammunition, the rear echelon is left far behind, and soldiers are so tired that they cannot carry out their tasks. They drop into the snow and fall sleep. I’ve seen an artillerist who was asleep two paces away from a firing gun. I stepped on a sleeping soldier, and he didn’t wake up. They need rest. Twenty-four hours – well, even eight hours would be good. Let the reconnaissance company advance.

‘The men in one of my companies were so fast asleep that they didn’t want to wake up even when the Germans were pricking them with their bayonets. The company commander was awake and with his sub-machine gun managed to hold the Germans off. That’s why it’s clear, one shouldn’t overstrain the men, no good will come of it.

‘One should evaluate absolutely clearly, soberly, what one has done to the enemy: defeated them, or just pushed them back. Don’t announce that you’ve defeated the enemy. They might retreat a bit, and then hit you hard right in the face.

‘I could see that the enemy was strong, rear echelons were left behind, and [front headquarters] was telling me: “Forward, Forward!” That way ruin lies. That’s what happened to Popov.’

5

‘We don’t really know [enough about] the enemy, and sometimes reconnaissance disorientates us.

6

Where the enemy is, what they are doing, where their reserves are, where they are going. One has to fight blind without all this information.

‘The main conflict with higher commanders occurs because they always think that the enemy is weaker than the enemy really is, but I, I do know what strength the enemy really possesses. There I was, with fifteen machine guns facing me, and they were shouting at me: “Go forward!” And I knew that there were fifteen machine guns that I had to suppress. But it also happens that a commander shouts: “I am up against thirty tanks,” when in fact there’s just one tank. That’s why there is mistrust.

‘There are young commanders who have seen nothing but the offensive,

7

so when they had to organise defensive positions, they didn’t know how to dig trenches or even why they should dig them at all, how to organize fire, etc. We also have another type of commander – those who were always on the defensive and are afraid to advance.

‘A bad thing about defensive battles is that people lose confidence in their strength, and they become depressed. In defence, the faith in victory becomes weaker, as well as faith in one’s strength. In defence, troops need more moral strength, while in the advance, more physical effort is required, and spirits are high . . .

‘Once we had dug in, men became used to German tanks

[attacking them]. You know, when I was sitting in the trench I felt I would have run away, but there was nowhere to run away to. Three or four men sit in a trench at a time, the rest are in

zemlyankas

, in “Lenin tents”.

8

If the enemy stirs just a little, I give a ring and everyone jumps out.’

The need to resist the fear of tanks was vital on the Eastern Front. The Germans even had a special name for the phenomenon –

Panzerschreck

. Before his Siberian troops crossed the Volga to defend the factory district of Stalingrad, General Gurtyev made them dig practice trenches on the west bank and then ordered some tanks to run over the trenches with the men in them. A tank running over a trench was known as ‘ironing’. The vital lesson was to dig deep, so that the trench would not collapse, and the soldiers in it would keep their nerve. There were many stories about such incidents.

An enemy tank had ironed the trench of machine-gunner Turiev, but he began to fire at the slits, and then at the file of enemy infantry, which dropped flat under his fire. When the men in the tank noticed this, they turned the tank back, and drove it over Turiev’s trench. Then this brave soldier took his machine gun, crawled from under the tank, settled by a haystack and began to mow the Germans down. This way hero Turiev went on fighting until he died, crushed by the tank.

Grossman also talked to one of Belov’s subordinate commanders, Martinyuk.

Once, I nearly shot him [Zorkin] when his regiment started to run away and he lost control, lost his head and did not take measures. Zorkin changed by December. They now call him the “professor”, he sits over maps, thinking, while German tanks are advancing. Now, after the advance battles, the middle-rank commanders are mostly those promoted [from soldiers and sergeants].

‘Commanders are being pushed aside from the political work while deputy commanders [i.e. commissars] are occupied entirely with political work.’

This was a rather euphemistic observation on the situation following Stalin’s Decree No. 307 of 9 October 1942, which re-established the single command and downgraded commissars to an advisory and ‘educational’ role. Commissars were shaken to find in many cases how much Red Army officers loathed and despised them. The political department of Stalingrad Front, for example, complained bitterly to Aleksandr Shcherbakov, the head of the Red Army’s political arm, GLAVPURRKA, about the ‘

absolutely incorrect attitude

’ which had emerged.

‘There’s a lack of affection and care towards Red Army soldiers; on the other hand, our commanders aren’t [sufficiently] demanding. This comes from the lack of culture. Why did Red Army soldiers love Lieutenant Kuznetsov? Because he cared about them; he lived with them. They would come to him with both bad and good letters from home, he promoted men, he wrote about his soldiers to the newspaper. Yet he punished negligent soldiers. He never overlooked the smallest sign of negligence: a button missing, someone coughing on a reconnaissance mission. Care [also means checking]: have you got cartridges, have you got dry foot bandages? It often happens that because of giving our work insufficient thought we lose people and don’t accomplish our mission.

‘Soldiers who have been promoted as officers fulfil their tasks extremely well and are very attentive towards their men. As far as everyday life is concerned, combatant officers are usually upright characters. In rear units, corporals, orderlies of regiment commanders, quartermasters in regiments and battalions – these are the most susceptible to moral degeneration in everyday life.

‘The phrasing of an order – “If you don’t go forward now, motherfucker, I’ll shoot you” – comes from a lack of will. This does not persuade anybody, this is weakness. We are trying to reduce such cases, and there are fewer and fewer of them. However, it would be very, very useful to raise this problem.

‘The nationality issue is quite all right. There are individual cases when it isn’t, but they are exceptions.’

This is an optimistic view of the nationality question, to say the least. The sometimes arrogant attitude towards ethnic minorities within the Red Army, particularly those from Central Asia, made notions of ‘

Soviet brotherhood

’ sound very false. Although no figures are available, the rate of desertion and self-inflicted injuries appears to have been much higher

among soldiers from Central Asia. The only solution of the political department was: ‘

To indoctrinate soldiers and officers

of non-Russian nationality in the highest noble aims of the peoples of the USSR, in the explanation of their military oath and the law for punishing any betrayal of the Motherland.’

‘There are lots of people who come to us from the occupied territory; they believe in the strength of the Red Army and are witnesses, sober and useful to us, of the occupation regime.’

Once the Germans began to retreat, many more stragglers and civilians from the occupied territories were incorporated into the Red Army. They were indeed useful to political officers in their propaganda sessions calling for revenge on the violators of the Motherland, but many were arrested by the NKVD or SMERSh as deserters or potential traitors.

Meeting of snipers at corps headquarters.

Solodkikh: ‘Actually, I am from Voroshilovgrad myself, but I’ve become a sniper instead of a collective farmer.’

Belugin: ‘I am from the occupied territory. I used to be nothing, but now, in defence, we aren’t [a waste of rations]. I was sitting, observing. Strizhik said to me: “No nonsense, all right?” The regimental commander, a clever chap, said: “Get a tongue.

9

It’s not so good to have to report at divisional headquarters without one.” Even if there were to be a hundred Germans against me, and I’m on my own, I would fight just the same, I’ll get killed anyway. I had been dying in prison for ten months, I jumped from the train which was moving at full speed, in order to get back to our people. My boy was killed because he was called Vladimir Ilich.’

10

Khalikov: ‘I’ve killed sixty-seven people. I arrived at the front speaking not a single word of Russian. My friend, Burov, he taught me Russian, I taught him Uzbek. On one occasion, no one wanted to eliminate a machine-gun pillbox. I said, I’ll knock it out. [I found

that] there were twelve men around, all pure-bred Germans. I camouflaged myself well and my heart was working well. I took out all the twelve Germans. I never hurry, if my heart is beating fast, like a propeller, I never shoot. When I hold my heart, I shoot. If I shoot badly, it would kill me. I took the binoculars from round a [German] officer’s neck. I reported to the

politruk

, “I carried out your order, and I’ve brought you a present.”’