A Writer's World (15 page)

Read A Writer's World Online

Authors: Jan Morris

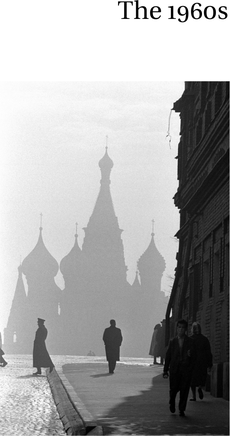

By the 1960s, as the memories and effects of the Second World War began to fade, the Cold War was in full blast. The Iron Curtain was clamped, as Churchill said, from Stettin on the Baltic to Adriatic Trieste, a gloomy barrier between capitalist and communist Europe. The Americans and the Russians implacably presided over their respective spheres of influence, as the old imperialists used to say, and Germany was divided between the ideologies. The sub-cultures of the hippies and the flower people flourished â they called it the Age of Aquarius, or the Permissive Age â and a new familiarity with drugs hard and soft added equivocal nuances to the scene. The 1960s ended with a Grand Slam â and a Cold War triumph for the United States â when two American astronauts became the first human beings to step upon the surface of the Moon.

I spent the decade partly writing for newspapers and magazines, partly writing my own books.

In 1961 I returned to Jerusalem, for the

Guardian,

to report upon the trial of

Adolf Eichmann, prime agent of the Nazi plan to exterminate Europe’s

Jews – the ‘Final Solution’. He had been kidnapped by Israeli agents in

Argentina a year before and had since been held incommunicado in

Jerusalem. I interpreted the event not as a show trial exactly, but certainly

as an expression of Jewish symbolism.

At eleven o’clock on the twenty-fifth day of Nissan in the Hebrew year 5721, Adolf Eichmann the German appeared before a Jewish Court in Jerusalem charged with crimes against the Jewish people – and in that very sentence, I suspect, I am recording the whole significance of this tragic and symbolic hearing. All else is incidental – the controversy, the evidence, the implications, the sentence, the verdict. The point of the Eichmann trial is that it is happening at all, and that through its ritual the Jews have answered history back.

Eichmann slipped into court this morning, out of the mystery and legend of his imprisonment, almost unnoticed. Heaven knows the courtroom was ready for him. Its parallel strips of neon lighting gave it a pale and heartless brilliance. Its great Jewish candelabra shone gilded on the wall. There sat the five Jewish lawyers of the prosecution, grave-faced, mostly youngish men, with a saturnine bearded head prosecutor, lithe and long limbed, elegant in his skullcap at the end of the line. There sat Dr Servatius, the German defence counsel, earnest in discussion with his young assistant. There were the translators in their booths, and the girl secretaries at their tables, and the peak-capped policemen at the doors, and the gallimaufry of the press, seething and grumbling and scribbling and making half-embarrassed jokes in its seats. And there stood the bullet-proof glass box, like a big museum showcase – too big for a civet or a bird of paradise, too small for a skeletonic dinosaur – which was the focus and fulcrum of it all. Nothing had been forgotten, nothing overlooked. We only awaited the accused.

But when he came most of us were looking the other way. He slipped in silently, almost shyly, flanked by three policemen in their blue uniforms. No shudder ran around the courtroom, for hardly anybody noticed. ‘There he is,’ I heard a voice somewhere behind my shoulder, rather as you sometimes hear mourners pointing out rich relatives at a funeral: and, sure enough, when I looked up at that glass receptacle there he was.

He looked dignified enough, almost proud, in horn-rimmed glasses and a new dark suit bought for him yesterday for the occasion. He looked like a lawyer himself, perhaps, or perhaps a recently retired brigadier, or possibly a textile manufacturer of vaguely intellectual pursuits. When I looked at him again, though, I noticed that there was to his movements a queer stiffness or jerkiness of locomotion. He hardly looked at the courtroom – he had nobody to look for – but even in his small gestures of preparation and expectancy I thought I recognized the symptoms: somewhere inside him, behind the new dark suit and the faint suggestion of defiance, Adolf Eichmann was trembling.

Like a candidate at a viva voce he rose to his feet, as though he were holding his stomach in, when the three judges entered the court: Dr Moshe Landau, Dr Benjamin Halevi, Dr Yitzhak Raveh – European Jews all three of them, and two of them from Germany itself, whence they escaped almost at the moment when the racialists came to power. They were solemn, bare-headed and commanding, but the proceedings opened paradoxically without dignity, for at this moment the myriad attending journalists found that their portable radio sets, for simultaneous translations, did not seem to work properly, and the Eichmann hearing, this moment of Jewish destiny, began to a cacophony of clicks, muffled shakings and tappings of plastic. ‘Are you Adolf Eichmann?’ asked Dr Landau, the president of the court: and through the racket around us we heard him answer, via microphones and wires out of his glass insulation. ‘Yes, sir,’ he said, and the trial began.

*

Eichmann is charged on fifteen counts under the Israeli Nazi and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law. It took Dr Landau more than an hour to read the indictment, with Eichmann almost motionless on his feet throughout it all. The ghastly essence of the charges is that he caused the killing of millions of Jews as head of a Gestapo department; that he was responsible for their slavery, deportation, spoliation and terrorization; and that he committed similar acts against Poles, Slovenes, Gypsies and Czechs.

As soon as these terrible accusations were pronounced (Eichmann twitching sometimes during the recitation, but mostly rigid as marble) Dr Servatius rose to his feet to present his objections to the jurisdiction of the court. He is an elderly man, slightly stooping, long practised in the defence of accused Nazis, and the burdens of his arguments were familiar to everyone in the building before he began. Dr Gideon Hausner, the attorney-general, replied at length, and as he argued on through the hours, opening and closing his law books, tucking his hands beneath his gown like an insect’s legs within its shards – as he reasoned on most of our feckless minds, I suspect, began to wander. We left that courtroom to its aridities, and we surveyed the centuries of antagonism that were the preliminary hearings of this trial, the medieval ghettos and the American country clubs, the fears and the snubs and the envies and the gas chambers. We wondered if history had a pattern after all, and we put ourselves in Eichmann’s enigmatic posture, and speculated if he had ever, in his most hideous nightmares, imagined himself sitting thus, immured in a big glass specimen case, with the power of Jewry everywhere around him, and keen, cold Jewish brains weaving their litigation all about.

*

There he sits between his policemen, unchanging, impassive, characterless but unforgettable. He never looks afraid, he never looks despairing, he never gives the impression that he may throw himself screaming against the glass walls of his cage or burst into tears, or even pluck our hearts with the agonizing old dilemmas of patriotism and loyalty.

There he sat, pursing his lips, until the president told him to stand, and he leapt nervously to his feet like a boy in the headmaster’s study. Did he plead guilty or not guilty to the first count of the indictment against him (causing,

inter

alia

, the killing of millions of Jews)? ‘In the sense of the indictment – not guilty,’ said Eichmann. Did he plead guilty or not guilty to the second count (

inter

alia

, forcing millions of Jews into labour camps)? ‘In the sense of the indictment – not guilty,’ said Eichmann. So they went through the fifteen counts of the indictment, through all its fearful charges of murder, cruelty and extortion, and to each Eichmann replied in a flat but unquavering voice: ‘In the sense of the indictment – not guilty.’ Very well, then, the court seemed to say, as Eichmann sat down again, put on his earphones, and bent towards the triple mouths of his microphone. Very well, then, let history speak.

*

Instantly Hausner rose to his feet, and began his speech with an intensity so passionate, with a sense of history so overwhelming, with a pride so

harnessed but so patent, with a burning Jewishness so hunted but so hunting, that for a few seconds we seemed posed on some plane outside time or space, where the voices of all the Jews of all the centuries could speak at once and in unison.

I shall never forget the moment. For me it was as though a shutter had been opened, if only temporarily, through which we Gentiles could peer into the heart of Jewry, and out of which, if only for a century or two, the Jews themselves could speak with dignity. This was the meaning of the trial, and is perhaps the meaning of Israel, and for Dr Hausner himself it must have been a moment of tragic exaltation.

This is how he began his speech:

‘When I stand before you, judges of Israel in this court, to accuse Adolf

Eichmann, I do not stand alone. Here with me at this moment stand six

million prosecutors … Never down the entire blood-stained road

travelled by this people, never since the first days of its nationhood, has

any man arisen who has succeeded in dealing it such grievous blows as

did Hitler’s iniquitous regime, and Adolf Eichmann as its executive arm

for the extermination of the Jewish people. In all human history there is

no other example of a man against whom it would be possible to draw

up such a bill of indictment as has been read here.’

How would you feel, to have such a thing said of you, in the fifty-fifth year of your life, thousands of miles from anyone you love, in the hands of people who hate you? How would you feel to hear yourself numbered, as Eichmann did a moment later, with Genghis Khan, Attila, and Ivan the Terrible, whose barbarous crimes of blood-lust ‘almost pale into insignificance when contrasted with the abominations, the murderous horrors’ to be presented at your trial?

I looked at Eichmann to see how he was reacting, half-expecting to see some flicker of perverse pride crossing his face, to be counted among such fearful company. But he was sitting well back in his chair now, with his hands in his lap, blinking frequently and moving his lips, and he reminded me irresistibly of some elderly pinched housewife in a flowered pinafore, leaning back on her antimacassar and shifting her false teeth, as she listened to the railing gossip of a neighbour.

Presently, in any case, the prosecutor descended from the terrible general to the beastly particular, and proceeded to describe, in icy detail and precision, step by step and horror by horror, the rise of Nazi Germany, the importance of anti-Semitism to its gimcrack philosophies,

and the familiar but always staggering techniques of the extermination camps. This was Eichmann’s country. He was always a conscientious administrator, they say – a killer behind a desk is how the prosecution has described him – and this systematic documentation must have suited his style. Earnestly and attentively he sat through it all, and it was only towards the end of the morning, several hours, ten thousand words and an eternity of horrors later, that the old lady in the pinny began to fidget and sway a little in her chair, as though she were pining for a nice hot cup of tea.

*

The massive symbolism of the trial is momentarily in suspense, and the court has now turned to the examination, if not the dissection, of that extraordinary minor organism, Adolf Eichmann himself. The immemorial shades of anti-Semitism still haunt the courtroom, but mostly we are now concerned with Nazi Germany, surely the meanest and most squalid of all tyrannies: and what has emerged from the hearing this morning has been the uncanny confusion of values within the fraudulent faith of Nazism – the total inability it fostered to distinguish not just the right from the wrong, but the important from the trivial, the relevant from the immaterial, the murderous from (to use one of Himmler’s favourite words) the inelegant.

This morning we have been hearing, in the accused’s own tape-recorded evidence, about his introduction to the techniques of Jewish extermination. It was extracted from him during several months of pre-trial questioning in Israel, and when you hear it from his own lips it is not so much the appalling horror of it all that flabbergasts you, but the apparently totally unwitting incongruity. At the very beginning of this testimony there is a faint, confused suggestion of imperial power, of the rolling thunder and spaciousness that you might expect of a conquering people, but that was in the event so totally lacking from Hitler’s Reich. ‘Shall I begin with France?’ Eichmann asked his interrogators. ‘Did it begin with France at first? How it began there, or whether it was in Holland – did it begin there? … What happened in Thessalonika? The Aegean? How was it in Bratislava, when it first began there? When did Wislicency reach Bratislava and how was it in Romania?’

Dim echoes of St Paul, of Doughty, perhaps of Homer ran through my mind as I heard this magnificent opening: but in a matter of moments the whole style of the thing collapsed, and we were left with a recital so horrible, shameless, cracked, and incredible that it could only have sprung out of Nazi Germany. For Eichmann then went on to describe his first introduction

to the idea of the ‘final solution’. Heydrich told him about it, he said. ‘The first moment I did not grasp his meaning because he chose his words so carefully. Later I understood and did not reply. I had nothing to say … of such a solution I had never thought.’ Before long though he was sent to Lublin to inspect an extermination operation, at a camp near by, where the engine of a Russian submarine was to be used to asphyxiate prisoners.

‘This was something terrible. I am not so strong that a thing like this should not sway me altogether. If today I see a gaping wound, I can’t possibly look at it. I belong to that category of people, so that very often I am told I couldn’t be a doctor …’ The other thing that worried him, mentioned in precisely the same, rather peevish tone of voice, was the enunciation of the police officer in charge of the camp’s construction. ‘He had a loud voice, ordinary but uncultured. He had a very common voice and spoke a south-west German accent. Maybe,’ – said Eichmann priggishly of this character, met so briefly twenty years ago on the threshold of hell – ‘maybe he drank.’ Similarly at Lwow, which Eichmann visited after watching them shoot Jews in a pit at Minsk (‘my knees went weak’), he remembered most vividly the charming yellow railway station built in honour of the sixtieth year of Franz Josef’s reign. ‘I always find pleasure in that period, maybe because I heard so many nice things about it in my parents’ home (the relatives of my stepmother were of a certain social standing).’

But if some of the incongruities of this testimony are trivial, one at least is fundamental: the prissy, goody-goody, obsequious quality that pervades this man’s confessions. We must not, I suppose, prejudge the issue, but there is at least no doubt at all that Eichmann was a prominent and powerful Nazi, a senior officer of the SS and a man close enough to the springs of power to be entrusted with the execution of the final settlement – ‘special treatment’, to quote another Nazi euphemism for slaughter. Yet he talks, or tries to talk, like a misled, misunderstood Mr Everyman mixed up in nasty events he did not comprehend, and governed by the overwhelming sense of dutiful obedience he picked up at his mother’s knee.