Adrift (13 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

Cleaning the dorados has become more thorough and pristine. After removing the organs from the organ cavity (I), the body is divided into segments (A, B, C), head, and tail. The segments can be cut into strips and hung up to dry. The muscle fibers run the length of the fish and become more tendinous at the tail. The tastiest and most tender steaks are cut from the back, above the lateral line (J), and closest to the head. A couple of steaks for immediate consumption may be cut from section A across the muscle fibers. All others must be cut lengthwise so they can be hung without falling apart. The organ cavity (I) ends at about mid-section (B). Aft of this, sticks can be cut below the lateral line (J) as well as above it. In the cross section, the backbone (G) and the bones that support the fin divide the body into quadrants, which are cut off of the bones before the flesh is sliced into sticks. A small amount of fat is found in belly steaks and in the meat attached to the pelvic and pectoral fins (F); I call this my fried chicken. A steak (D) can be cut from the side of the head. The eyes with their associated muscles and fatty fluids (E) provide moisture. The eyes, small bits of meat scraped off the head, organs, and a couple of steaks provide the first meal. The backbone, ribs lining the organ cavity, and fins are saved along with the fish sticks for later meals.

Finally I manage to spear a triggerfish. The tiny fillets are little comfort, but she is full of sweet eggs. My body seems to immediately revive from the nutrients. A third ship approaches, but farther off. I fire a flare. It passes. I now have only two meteor, two smoke, and two parachute flares left. The ships have been eastbound, three or four days apart. I must be near the lanes. Perhaps I'll be lucky the fourth time.

FEBRUARY

26

DAY

22

It is February 26, my twenty-second day adrift. I cannot complain too much as the morning has been relatively good. The raft is moving well, the sun is out. My second dorado lies slain before me. My cleaning of the dorados has become more thorough. I don't waste anything. I eat the heart and liver, suck the fluid from the eyes, and break the backbone to get the gelatinous nuggets from between the vertebrae. I have rationed myself only a half pint of drinking water per day, so I have built up my stock to six and a half pints. I am clear-headed, and the raft is holding up. I am feeling O.K., but I am very conscious that my spirits fall and rise with the undulating waves.

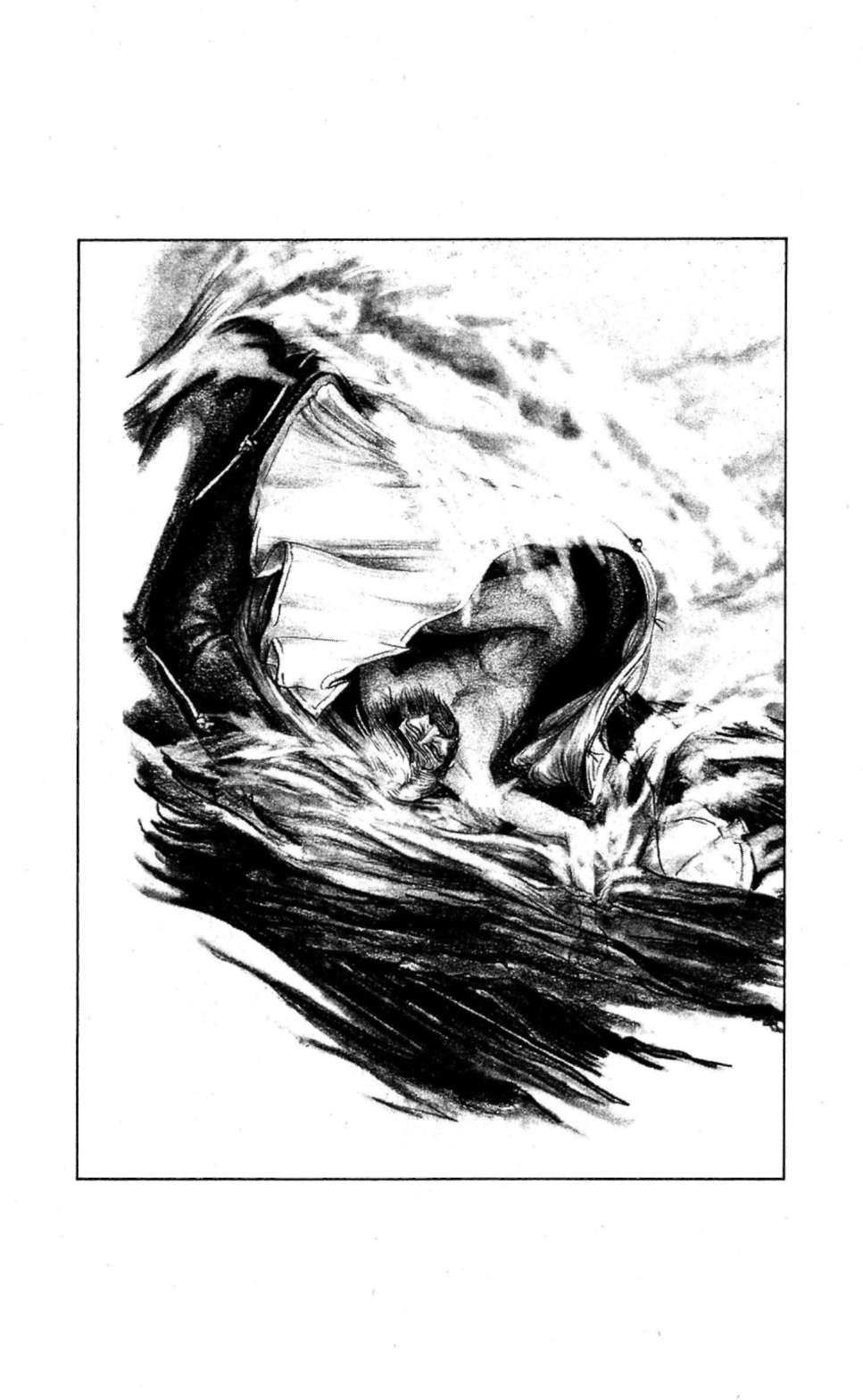

Then the afternoon sun focuses on me. Magnified as if through a glass, it seems to burn holes in my chest. I struggle to my knees in order to tend the still and look around. Dizziness overtakes me, nearly knocking me over as darkness closes in on the edges of my vision. All is blue and hazy as I fumble for the coffee can and pour water over my scalp. I collapse, vaguely seeing waves press ahead to my destination.

Like a thunderclap, the windward side of the raft crushes in upon me, flips forward, and the bow digs into the sea. Water pours in. This is itâcapsize, I think calmly, but the stern pops back into shape and flops down. About twenty gallons of water slosh around me. My sleeping bag, some notes, the cushion, and other gear float about. The rogue wave melts into the distance ahead, a messenger signaling that worse is to follow.

The flooding has revived me from catatonic lethargy. Mechanically I set to the exhausting work of bailing and wringing out. Another three days of cold, wet gear. My sleeping bag is already a bundle of knots and lumps, encrusted with salt when dry. It is hard work just to wring out most of the water and get the bag to the merely wet stage. In the ensuing evenings, the crinkly, clammy space blanket will provide my best cover. My scabs have been torn off again. The suddenness of these sieges by the sea and its creatures gives me no quarter.

I stand, face the growing wind and seas, and support my wobbly legs by holding on to the canopy. Waves jostle my platform and gurgle about my feet. Cirrus clouds mat the sky like shaggy white dog hair dropped from the heavens. Things are getting bleaker both inside and out.

I try to keep a positive perspective. The essentialsâfood, water, shelterâare being maintained. My mind is sometimes free to wander and to make my life more than the here and now. I am the past. I am what others have known and felt about me. I am the things I have done. These are my afterlife. These cannot be captured or killed. I know this is only temporary reassurance, but I am inspired enough to regularly get up off my cushion, feel the cold air against my skin, and survey my surroundings. I cannot afford to miss a passing ship.

I find a small hole in the second still, tape it up, and get it temporarily working again, continuing to build my water stock. No matter how positive I try to be, approaching scud and wind blow upon me the fear of another gale.

By morning the wind is whistling. The heaving sea raises ten-foot waves, which spew, curl, and crash down. I hang on to windward, wrapped in my salty sleeping bag. In quick darts to the downwind side, I tend to the solar still and snatch a glance about. Watch-keeping is a joke. The visible horizon is very close. I stand and balance as well as I can on the rubber floor, rising and falling with the waves. As the raft is elevated to the peak of a wave, I bend my knees to compensate for the liftoff. We hesitate for a moment on the top before plunging down into the trough. During this brief pause, my eyes sweep across a segment of the horizon. It takes a couple of minutes of rising and plummeting before I get a clear look all around. Every now and then I get a glimpse of something off to the north. But the massive, rolling shoulders and white foamy heads of waves crowd my view. Finally I'm lifted to the top of a big roller. Yes! There she is! A ship, northbound. Unfortunately, there's no hope of her picking me up. She's pointed away from me and too distant to spot a flare. I am encouraged only by her directionâSouth Africa to New York. What was merely a dream twenty-four desperate days ago, I have made real. I have reached the lanes and I still live.

T

HE METAL IS HARD

and cold. After an hour of leaning over the bulwark, my elbows are in icy pain. I stand and thrust my hands deep into the wool coat the captain has brought me. "I'll bet you never thought you'd see this city again," he says, looking at me quizzically. I peruse the horizon. It is no longer flat and empty but is full of monolithic skyscrapers, gray smog. The noise of the city rises above even the rumble of reversed engines. Heavy, tattooed arms pull aboard hawsers as thick as thighs and whip them around the capstans. Slowly the ship is worked in to the dock. More and more lines are tossed and set. The water eddies around us. The behemoth is reeled in. No, I never thought I'd see New York again.

Then there is darkness and chaos. My head is struck with a club, cold, wet, and hard. The assaulter roars, rumbles, and rolls away into the night. I am on the dark side of the earth, a quarter world away from New York. The wind is up and so is the sea.

Rubber Ducky

lurches and crashes as if caught in a demolition derby. "Still here," I moan.

Each night, soft fabrics caress my skin, the smell of food fills my nostrils, and warm bodies surround me. Sometimes while wrapped in sleep I hear my conscious mind bark a warning: "Enjoy it while you can for you will soon awaken." I am used to the duality of it. Usually when I sail alone, the sounds of fluttering sails and waves, the motion of my boat rising and plunging, never leave me even as I hang in my bunk dreaming of faraway places. If a movement varies slightly or an unfamiliar noise slaps against my eardrum, I am immediately awakened. Yet last night's dream was almost too real. My life has become a composition of multilayered realitiesâdaydreams, night dreams, and the seemingly endless physical struggle.

I keep trying to believe that all of these realities are equal. Perhaps they are, in some ultimate sense, but it becomes increasingly obvious that in the survival world my physical self and my instincts are the ringmasters that whip all of my realities into place and control their motions. My dreams and daydreams are filled with images of what my body requires and of how to escape from this physical hell. Since I have gotten the still to work and have learned how to fish more efficiently, there has been little to do but save energy, wait, and dream. Slowly, though, I find I am becoming more starved and desperate. My â equipment is deteriorating.

I must work harder and longer each day to weave a world in which I can live. Survival is the play and I want the leading role. The script sounds simple enough: hang on, ration food and water, fish, and tend the still. But each little nuance of my role takes on profound significance. If I keep watch too closely, I will tire and be no good for fishing, tending the still, or other essential tasks. Yet every moment that I don't have my eyes on the horizon is a moment when a ship may pass me. If I use both stills now, I may be able to quench my thirst and keep myself in better shape for keeping watch and doing jobs, but if they both wear out I will die of thirst. My mind applauds some of my performances while my body boos, and vice versa. It is a constant struggle to keep control, self-discipline, to maintain a course of action that will best ensure survival, because I can't be sure what that course is. Is my command making the right decisions? Might immediate gratification sometimes be the best course to follow even in the long run? More often than not, all I can tell myself is, "You're doing the best you can."

I need more fish, and the constant nudging I feel through the floor of the raft tells me that the dorados are around in sufficient numbers to make fishing a reasonable expenditure of energy. After several misfires, I finally skewer a dorado by the tail, but it doesn't slow him down much. He yanks the raft all over the place while I frantically try to hold on, wishing that I could train these fish to pull me in the direction I want to go.

He pulls free before I can get him aboard. Oh well, try again. I start to reset the spear gunâbut the power strap is gone, now sinking through three miles of seawater! This could be real trouble.

It's my first major gear failure; but I've dealt with a lot of jury rigs before so I should be able to figure something out. It's always a challenge to try and repair an essential system with what one has at hand. In fact, I sometimes wonder if one of the major reasons for ocean racing and voyaging is to push one's self and one's boat just past the edge, watch things fail, and then somehow come up with a solution. In many ways, having a jury rig succeed is often more gratifying than making a pleasant and uneventful passage or even winning a race. Rising to the challenge is a common thread that runs through a vast wardrobe of sea stories. I've stuck back together masts, steering gear, boat hulls, and a host of smaller items. Although I don't have much to work with, repairing the spear should be relatively simple.

The important thing is to keep calm. The small details of the repair will determine its success or failure. As always, I can only afford success. Don't hurry. Make it right. You can fish tomorrow. The arrow and the gun handle are still intact. It is only the source of power that is missing. I put the arrow on the shaft of the handle in the normal manner, but I pull the arrow out through the plastic loop on the end of the handle shaft in order to lengthen the weapon as much as possible. I wind two long lashings around the arrow and shaft. I use the heavy codline, which is better than synthetic line because it shrinks when it is wetted and then dried, thereby tightening the lashings. The smooth arrow still rotates, so I add a third lashing, then I add frappings to the lashings. These are turns of the line around the lashings at right angles. When pulled tight the frappings cinch up the lashings and should keep them from spreading out haphazardly. There are notches in the butt of the arrow which normally fit into the trigger mechanism in the handle Through these notches and back through the trigger housing I pass loops of line to keep the arrow from being pulled out forward by an escaping fish.

I am aware that my repaired spear is a flimsy rig for catching dorados. Normally a diver pulls on his spear gun arrow when retrieving a fish. I must drive my lance through the fish, putting the rig in compression rather than tension. When I pull a fish out of the water, it will put a large bending load on the arrow as well. However, my new lance feels pretty sturdy, and I'm ready to try it out. Patience is going to be the secret, and strength. Power was stored in the elastic power strap; now the improvised spear has to be thrust at a moment's notice with all of the power I can muster if I'm to drive it through a thick dorado.

I lean my left elbow on the top tube of the raft to steady my aim, and I lightly rest the arrow of the spear between my fingers. I pull the gun handle high up onto my cheek with my right arm, tensed and steady, awaiting the perfect shot. I can sight down the shaft, and rocking back and forth gives me a narrow field of fire. On the water's surface is an imaginary circle about a foot in diameter into which I can shoot without moving my steadying elbow off the raft tube. If I am not well braced, my shots will become wild. The effective range of the spear has been shortened from about six feet to three or four. I must wait until a fish swims directly under my point so that it will be in range and the problem of surface refraction_which makes the fish appear to be where it is not_will be minimized. This problem is extreme at oblique angles to the water. When I shoot, I must extend my range and power as much as possible. I thrust my arm out straight and lunge as hard as can with mv whole body, trying to hold my aim. The shot must be instantaneous because the fish are so quick and agile, but it also must be perfectly controlled. Once I lift my left, steadying arm off of the tube, it becomes hopeless. I watch the fish swimming all over the place, but I must wait for one to swim within my field of fire. I remain poised for minutes that stretch into hours at a time. I feel like I'm becoming an ancient bronze statue of a bowless archer.